Pacific Voices, 2014 -2019

Edwin Battistella, Kristin Denham, Anne Lobeck

Progress report [12/2020]

Contents

1. Introduction 2

1.1 Challenges 2

1.2. Goals 3

1.3. Oregon and Washington 3

2. Pronunciation 5

2.1 The cot-caught Merger 5

2.2 Front vowels 7

2.3 Aaron and Erin, and Mary, merry and marry 8

2.4 Horrible 9

2.5 The pin/pen merger 10

3. Once-stigmatized forms: coupon and often 11

4. Two other problematic words: syrup and route 17

5. Lexical changes in progress 18

5.1 on accident and by accident 18

5.2 dude 20

5.3 legit(ly) 21

5.4 Hella 22

5.5 Your guyses 23

5.6 Jojos 24

6. Comparison with the Harvard Dialect Survey 26

7. A Reading Passage 30

8. What we learned and what’s next 32

8.1 Struggles 32

8.2 Learning opportunities 32

8.3 Next steps 34

References 35

Key words: Oregon, Washington, Low vowel merger, California vowel shift, Pacific Northwest speech, slang and language change.

1. Introduction

1.1 Challenges

One of the challenges of teaching linguistics, and especially of teaching linguistics to non-majors is to heighten students’ awareness of dialect diversity, dialect research, and dialect stereotypes. As professors, we discuss language variation in classes and elicit pronunciations, vocabulary and usage from students, but we often find students to be uncomfortable with the complexity of usage and sometimes nervous that they are not speaking properly. Students in the Pacific Northwest are often surprised to learn that they have dialects and that the speech of the Pacific Northwest might vary widely according to features of region, age, gender, ethnicity, education and social class.

And it’s not just students. When we talk dialect diversity with members of the general public, they are sometimes skeptical that the region would have a discernable accent or dialect. A historian colleague who read an essay on Pacific Northwest dialect perceptions questioned whether bag-raising was a real phenomenon and asked how dialects compared to other regional styles, like clothing and architecture. An administrator from Texas, reviewing a grant proposal, opined that Oregonians didn’t have an accent, “not like Texas.”

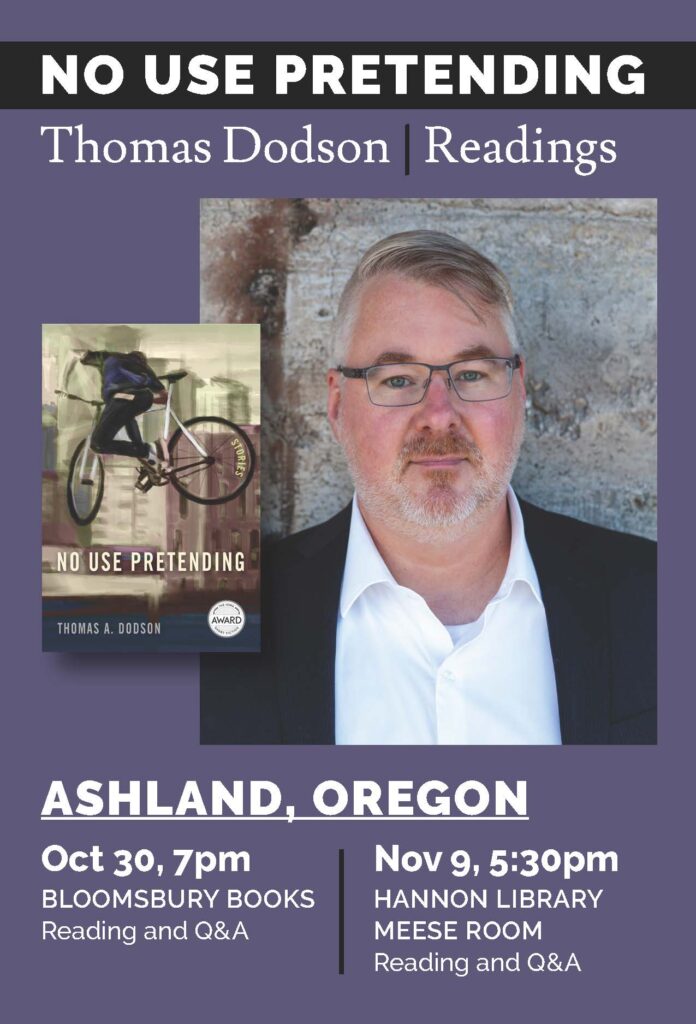

Here we report on some survey and classroom techniques to bring linguistic research into the classroom and engage students in exploring their own speech variation. Taking Ashland, Oregon, and Bellingham, Washington, as end points along the I-5 corridor of the Pacific Northwest, we piloted a survey of about 887 (mostly) students during the academic years 2014-2019 (continuing into the 2019-2020 academic year), asking about perceptions of pronunciation with a long-term goal of collecting demographic information. After obtaining IRB approval, we used the Qualtrics survey software to develop an online survey asking students 35 questions, 22 of which had to do with language and 12 of which were demographic, and a final question about using their survey results.

1.2. Goals

Initially, we had four goals. First, we wanted to give students an appreciation for the complexity of dialect data and the way in which representations of dialect (and data) are often abstractions. Thus, in class discussions, students often note that their own speech differs from textbook descriptions, and they cite various anecdotal examples and counterexamples from friends and relatives (“My boyfriend says EYE-ron and it drives me crazy,” said one student). By having students analyze actual data from their speech community, they can see where patterns exist and don’t, and they may become less judgmental about variation.

Second, we wanted to explore the various vowel shifts and the extent to which they might differently be showing up in the speech of northwest Washington (Bellingham is 21 miles from the Canadian border) and southwest Oregon (Ashland is 13 miles from the California border). We hoped that we might spark students’ interest in the topic of vowel shifts and phonetic variation more generally.

A third goal was to collect data on some potentially age- and social class-related items, such as the use of gender neutral dude, the double possessive your guys’s, hella, and legit, as well as the pronunciations of items like often and coupon.

Our fourth goal was to develop some questions, activities and exercises surrounding local dialects that would allow us to reinforce learning goals in linguistics as we discuss the survey results in classes.

Finally, in this initial phase of our work, we cast a wide net to experiment with the survey software and to determine both what was doable as researchers and what was important to teach in class. In the conclusion, we offer some suggestions for the future.

1.3. Oregon and Washington

The earliest languages spoken in the Northwest were those of immigrants from northeast Asia, traveling across the continental shelf into what is now Alaska and Canada, making their way along the Pacific coast and inland. As a result, the Northwest shows especially dense concentrations of pre-European languages. First contact by Europeans came by sea, when Spanish galleons landed along the coast of northern California in the mid-1500s. In 1778, on his third voyage to the Pacific, English Captain James Cook sailed to the central Oregon coast and in 1792, Captain Robert Gray of Rhode Island sailed into the mouth of the Columbia River, which Gray renamed after his ship, the Columbia Rediviva. The famous expedition of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and the founding of Astoria in 1811 helped to further establish the American presence in the Pacific Northwest.

From 1818 to 1846, the Oregon Territory was jointly occupied by British and Americans. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 fixed the boundary between Great Britain and America at 49 degrees. Once the border was established, American settlement in the Oregon Territory took off. In The Willamette Valley: Migration and Settlement on the Oregon Frontier, William Bowen writes that those settling in that area tended to be “disproportionately from the ranks of unmarried men from the Northeast or abroad.” The census of 1850 recorded 11,873 Oregonians, 60% of whom were males and most of whom hailed from the states of Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee and Ohio (Loy, et. al. 2001, 15).

According to Randall V. Mills, most settlers funneled through the Missouri and Iowa area while preparing to travel west on the Oregon Trail. The migration brought language to the new territory that incorporated the speech of many emigrants from New England or New York (Mills, 1950: 83). In Oregon, Mills proposed three broad founding dialect areas, a narrow strip along the Willamette River from Portland to Eugene, a more rural area extending from the Willamette River Valley to the Pacific Coast Range, and an area to the east of the Cascade Mountains and to the south of the Calapooya Mountains. As for Washington, Carroll Reed (1952) noted that while the Missouri element predominated in the areas of Washington adjacent to Oregon, spreading “all along the Columbia River, particularly in the areas east of Walla Walla,” other waves of settlers from Iowa, southern Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio predominated in the Pacific counties. According the Reed, “the speech of southern Illinois and Iowa may be considered typical for most of the state of Washington,” at least as far as the founder effect is considered.

Today both states are increasingly multilingual, though less so than much of the rest of the country. According to the data from the Language Map Data Center of the Modern Language Association, about 83 percent of the Oregon and Washington population speak English at home and about 17 percent speak a language other than English, with Spanish, Vietnamese, Russian, and Tagalog among the most robust. Apart from the founder effects and linguistic diversity, both Oregon and Washington have significant urban-rural divides and show the influence of emerging industries and of emigrants from other states.

Our subjects were 887 (mostly) students at Southern Oregon University and Western Washington University. Demographic data collected included age, gender, ethnicity, hometown, perceived social class, college major, and family household income. We also asked students’ self-perception of whether they were urban, rural or suburban and to rate themselves as speakers and writers of English.

2. Pronunciation

2.1 The cot-caught Merger

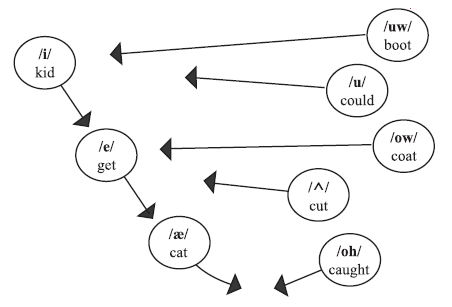

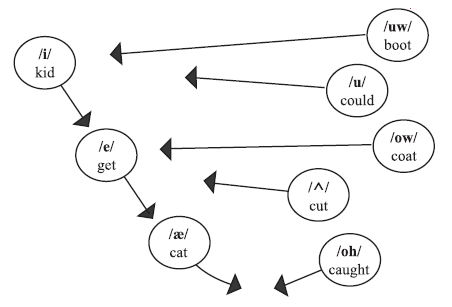

The Pacific Northwest is geographically situated between two current linguistic shifts in vowel production: the so-called California Vowel Shift and the Canadian Vowel Shift. The California Vowel Shift, shown below with the shifts represented by arrows, involves a fronting of the vowels produced in the back of the mouth—the long vowels boot and coat and the shorter vowels in could and cut being pronounced more toward the front of the mouth (approaching butte, key-oat, cud and ket), with the short front vowels being lowered and backed (kid toward ked, get toward gat and cat toward cot). At the same time, the earlier distinct vowels in cot and caught are merging. Linguistic shifts happen slowly over long periods of time, and are sensitive to style shifts and the performance of identity, but overall what had been a vowel trapezoid historically is becoming more of the vowel triangle.

(diagram from Ward, 41, from Hinton, et al.)

Not shown in the diagram is a counter-raising among the front vowels in syllables ending in velar consonants (g, k, ng). There, the lower vowels in the front of the mouth shift upward, yielding beg for bag, laig for leg, thenk (or even think) for thank, and so on. See Freeman (2013, 2014).

The elements of the California vowel shift are proceeding at different rates and are more prominent in different speech styles and some (such as the lowering and backing of /æ/ and the fronting of /uw/ have made their way into media stereotypes of the Valley Girl/Surfer Dude speech. Students are often aware of the fronting of /uw/ in their own speech as an aspect of speech style but seem to be less attuned to their backing of /æ/.

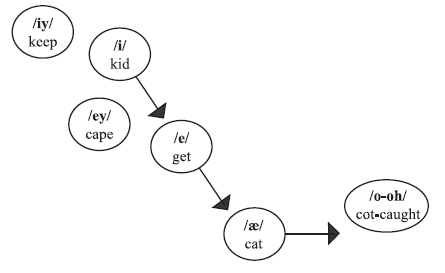

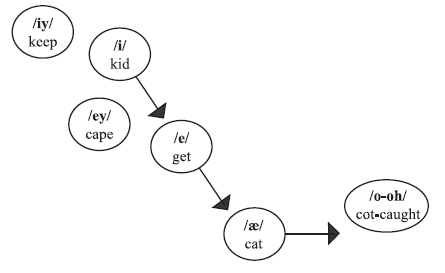

The Canadian Vowel Shift is similar to the California Shift in several respects. First described in 1995 by Clarke, Elms and Youssef, the shift also involves the lowering of the front lax vowels /æ/ (the short-a of trap and cat), /ɛ/ (the short-e of dress), and /ɪ/ (the short-i of kit). It also involves the merger of the cot and caught vowels, though the merged Canadian vowel is more rounded, slightly lower and slightly further back than the merged cot/caught vowel among many speakers in the U.S.

According to Charles Boberg, the retraction of /æ/ is being led by speakers from Ontario, in in east-central, and by women. The shift is somewhat less advanced among speakers from the other regions of Canada and among men (Boberg, 2005). In the Atlas of North American English, (Labov et al., 2006), it is suggested that about a quarter of speakers in the Western U.S., exhibit the Canadian Shift.

(diagram from Ward, 42 from Clarke)

When we discuss the vowel shifts in introductory classes, students are fascinated but also sometimes unsure of their own pronunciation. Thus we begin by collecting data on some of the more easily identifiable of the vowels involved in the shift, the vowel sounds in the names Don and Dawn. The don/dawn pair is salient for students because the orthography indicates the word difference and thus highlights the phonological merger. And often, someone knows in a class knows both a Don and a Dawn and can attest to the possibility of confusion arising from the merger. Two of our survey questions looked at this pair and at hock and hawk:

Q2 – How do you usually pronounce the vowel sounds in the words DON and DAWN? The same or differently.

Q19 – Do you pronounce the words HOCK and HAWK the same or differently?

81% said they pronounce don/dawn the same and differently and 83% pronounce hock/hawk the same.

It is worth asking at this point whether students are accurately able to self-identify their pronunciations in response to prompts. More research is doubtless needed on this topic, but in section 8 we report on a sub-study comparing actual pronunciation to reported pronunciation for 23 speakers. Here we found an 89% accuracy in identifying their own pronunciation.

2.2 Front vowels

We also asked a set of questions about the pronunciation of the front vowels in the words Craig, leg, and egg, where the vowels may be tensed /e/ or a lax /ɛ/. The name

Craig is word of Celtic origin and related to the Scottish Gaelic creag “rock,” and thus also to the word “crag.” The pronunciation varies in the English-speaking world, and in the U.S. and Canada it is often pronounced with the lax /ɛ/. Historically the pronunciation of Craig falls outside of the California/Canadian shift and the alternate pronunciations appear to be in fairly evenly distributed among Pacific Northwest speakers.

Q5 – Do you usually pronounce the name CRAIG as crAYg or crEHg?

59% reported pronouncing the name as crAYg and 41% as crEHg.

In leg and egg we were looking for evidence of raising of the vowel lax /ɛ/, to a tensed /e/. This is part of the counter-raising aspect of the California vowel shift in particular.

Q7 Do you usually pronounce EGGS more like EHggs or AIggs?

Q20 Do you usually pronounce the word LEGS more like LEHggs or LAYggs?

The results were:

Non-raised /ɛ/ Raised /e/

64% EHggs 36% AIggs

62% lEHgs 38% lAYggs

Most speakers reported pronunciations with a lax /ɛ/ though just over a third were egg and leg raisers.

In classes (and conversations, especially those with individuals in the service professions) we also find evidence of raising of the /æ/ vowel in thank, which is in a closed syllable before velar /ŋ/ and /k/. Thank you is sometimes pronounced /thɛŋkju/ or even /thInkju/. We return to thank you in section 8.1 below.

2.3 Aaron and Erin, and Mary, merry and marry

We also examined the pronunciation of the pair of names Aaron and Erin, which makes a nice pedagogical contrast with Dawn and Don. In most of the U.S., the pronunciation of Aaron and Erin is the same, with a mid-lax /ɛ/ rather than a low /æ/. American English merged the two sounds before /r/ while they remain distinct in the U.K.

Given this, we expect the American West to show the merger of these sounds quite robustly.

Q17 – Do you say the names ERIN and AARON the same or differently?

78% reported pronouncing the names the same.

The Aaron/Erin merger opens the door to classroom discussion of the three-way contrast before /r/ in the words Mary /e/, merry /ɛ/, and marry /æ/. In New England, New York City and Philadelphia and parts of the South, the three words are often distinct. In the Inland North and mid-Atlantic (excluding Philadelphia), there is often a two-way contrast of with Mary and merry pronounced as /mɛri/ and marry retaining the /æ/ (/mæri/). See Labov, et al. (2006), Dinkin (2005) and Gordon (2008), and Kretzschmar (2008) for more background and discussion. In much of the rest of the country, the three are merged as /mɛri/. For simplicity’s sake in the survey, we took for granted that Mary and merry would be homophones (pronounced as /ɛ /) for many speakers and focused on marry and merry.

Q 9 How do you usually pronounce the vowel sounds in the words MARRY and MERRY? The same or differently.

83% reported pronouncing them the same. 82 respondents reported pronouncing both marry/merry and Erin/Aaron differently, but 110 of those who pronounced marry/merry the same pronounced Erin/Aaron differently and 70 of those who pronounced marry/merry differently pronounced Erin/Aaron the same.

2.4 Horrible

The pronunciation of the word horrible (and similar words (such as orange, florist, and Florida) with /ɑr/ is common in the area including New York City, New Jersey, Philadelphia and the Carolinas. Elsewhere the pronunciation tends to be the /ɔr/, with the exception that Oregonians typical have an /ar/ in the state’s name. We expected the pronunciation of horrible to have the pervasive /ɔr/ we represented as HOAR-ible.

Q6 – Do you usually pronounce HORRIBLE as HAR-ible or HOAR-ible.

97% reported HOAR-ible.

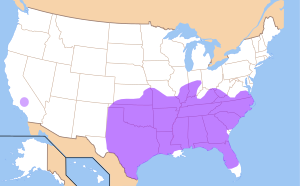

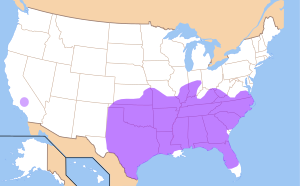

2.5 The pin/pen merger

The pin-pen merger is a merger of /ɪ/ and /ɛ/ before the nasal consonants [m], [n], and [ŋ], which predominates in the South, resulting in a near homophony in words like pen and pin, gem and gym, him and hem, kin and Ken, bin and Ben, and so on. Bailey and Maynor (1989, 13) report that the merger began “in the last part of the nineteenth century and worked its way to completion during the last half century.” The pin/pen merger is found in the Midland Regions (Labov, et al. 2006), has expanded west, and is widespread through Kansas City, Houston, Seattle, and Bakersfield, California (Strelluf 2014 and Koops 2008). Since parts of Oregon and Washington were settled by emigrants from the South, we were interested in testing the robustness of this merger in the Pacific Northwest. Impressionistically, it appears to be most prominent with speakers who have Southern roots or close relatives.

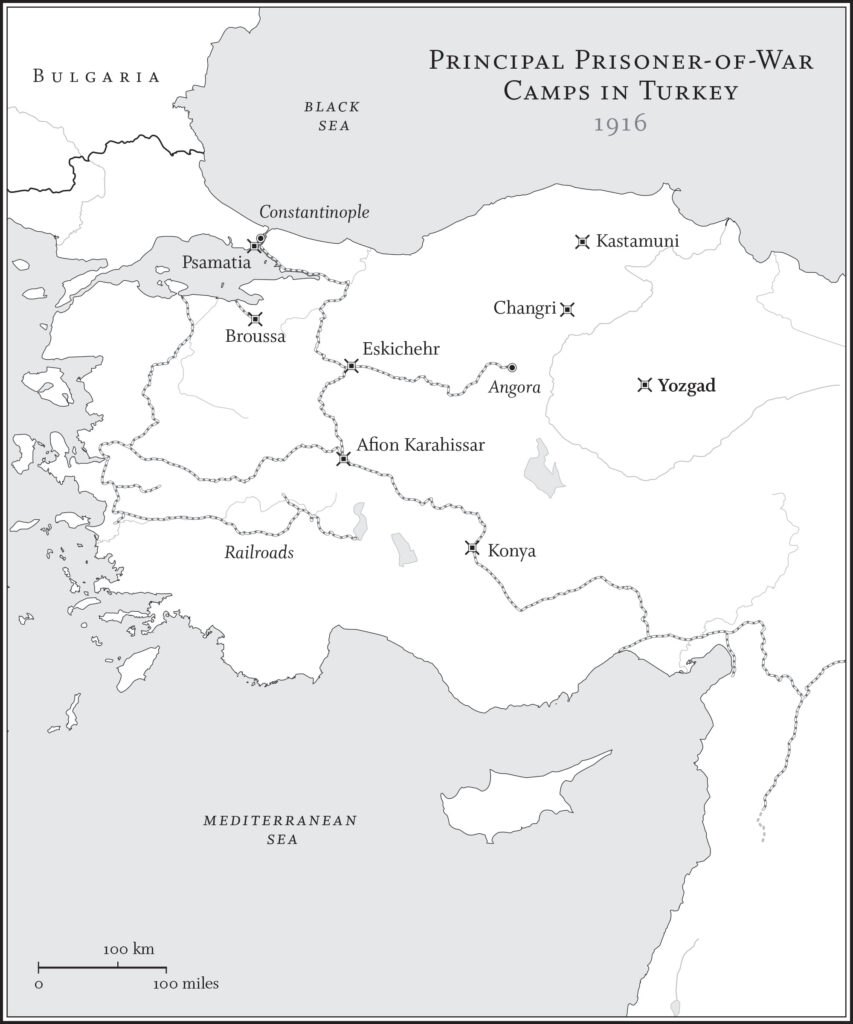

pin/pen merger areas in purple

We approached this obliquely by asking about the pronunciation of center, rather than pin/pen directly.

Q18 – Do you usually pronounce the first vowel of CENTER as sen or sin?

Speakers overwhelmingly selected the non-raised vowel. 96% reported the pronunciation SEN-ter. Of the 4% of respondents whose responses suggest that they have the merger (34 individuals) 8 were from the South or had lived in the South several of the Oregon, Washington, and California speakers reported rural identification.

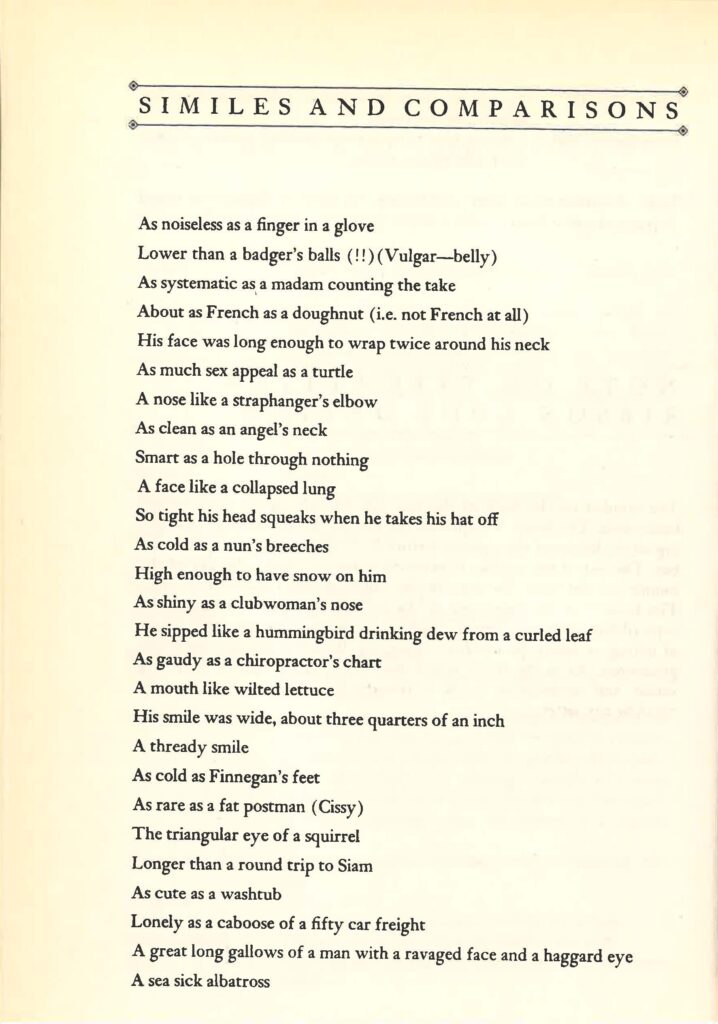

3. Once-stigmatized forms: coupon and often

There is of course more to speech variation than pronunciation of vowels, so we have also been collecting data on the pronunciation and use of lexical items that seem to be social variants. One of these is the pronunciation of coupon, which in American usage is pronounced with or without a glide following the initial /k/. The glide is a twentieth century development and was for a time stigmatized (and it remains a shibboleth for some speakers and in some pronunciation guides), though current dictionaries give it as standard. But while, dictionaries of American English give both pronunciations, older dictionaries and more prescriptive guides still treat the glide pronunciation as substandard (the Big Book of Beastly Mispronunciations, for example, calls it “Spurious” and Bryan Garner says that it “betrays an ignorance of French and of the finer points of English”). Nevertheless, in the U.S., pronunciations with a palatal glide (a /j/) before long /u/ are common after velar consonants (as in cute, cube, cue, Cupid, skew, factual, regulate, angular, and argue).

In the case of coupon, we offered speakers the third option of reporting that they pronounced it both ways. The speakers we surveyed reported a slight majority pronouncing the word as COOP-on but roughly a quarter consistently pronounce it with the glide (CYEW-pon).

Q8 Do you usually pronounce the word COUPON as COOP-on CYEW-pon? Or both ways.

58% reported the pronunciation COOP-on; 21% reported pronouncing the word as CYEWpon or CUEpon; 19% reported pronouncing coupon both ways.

In classes, the coupon item can lead to a discussion of the misleading role of etymology in judging pronunciation. Coupon can be traced back to the French word coup (meaning a blow, as in coup-contrecoup or coup de grâce and later an impressive act (as in a publishing coup). Coupon entered English in the 19th century, with a first OED citation from 1822. It was initially a financial term related to certificates attached to bonds. The meaning evolved to refer to prepaid ticket for travel and in the early twentieth century to the familiar sense part of an advertisement redeemable for a discount or free offer.

We also looked at what connections there are between self-perceptions of social class and of speaking/writing ability and pronunciation of coupon? There was relatively little difference across class.

|

Do you usually pronounce the word COUPON as: |

| COOP-on |

CYEW-pon |

I pronounce it both ways |

| How would you characterize your social class standing? |

Poverty Level |

40% |

42% |

44% |

| Lower Middle Class/Working Class |

| Middle Class |

13% |

19% |

19% |

| Upper Middle Class/Affluent |

47% |

38% |

37% |

|

Total |

493 |

206 |

174 |

We also looked at the self-reports of speaking and writing, and again there is very little difference. Interestingly the CYEW-pon speakers did not consider themselves less good English speakers or writers, suggesting that it is not stigmatized for them.

|

Do you consider yourself _____ speaker/writer of English |

|

| a better than average |

an average |

a worse than average |

Total |

|

COOP-on |

292 |

211 |

9 |

501 |

| CYEW-pon |

117 |

82 |

6 |

205 |

| both ways |

102 |

62 |

1 |

165 |

|

Total |

511 |

355 |

16 |

882 |

58% of COOP-on speakers considered themselves better than average as did 57% of CYEWpon speakers and 61% of those who pronounce coupon both ways. COOP-on is still the marginally dominant pronunciation but about 40% of respondents either pronounce the word CYEWpon or alternate. The results are consistent across social class and gender.

The situation for often, another former shibboleth, is somewhat more complex than that of coupon. The formerly stigmatized form AWFten is vastly preferred, though somewhat less so by females and urbanites. The preferences of the self-described middle class speakers are fairly close.

Historically, often comes from oft, and the /t/ was lost among educated speakers in the 17th century. But the /t/ was retained or reintroduced as a spelling pronunciation. Merriam Webster cites the pronunciation as \ˈȯ-fən, ÷ˈȯf-tən\, with the ÷ sign (the obelus mark) indicating “a pronunciation variant that occurs in educated speech but that is considered by some to be questionable or unacceptable.”

Others commentators are less diplomatic about the /t/-less pronunciation, with Elster’s Big Book of Beastly Mispronunciations calling it “less common in educated speech and far more often disapproved of by cultivated speakers—particularly teachers of English, drama, and speech.” Elster cites early twentieth century commentators who called it “vulgar” and “sham-refined,” or in Henry Fowler’s terms, practiced by “the academic speakers who affect a more precise enunciation than their neighbours … & the uneasy half-literates who like to prove that they can spell.” Garner refers to it as non-U usage (following the terminology of Alan Ross and Nancy Mitford for upper-class and non-upper-class usage and social practices in England).

Nevertheless, the speakers we surveyed pronounced the word without a /t/ by about three to one, though some noted in class discussion that they sometimes pronounce it either way.

25% reported pronouncing the word with a t (AWFTen)

75% reported pronouncing it without a t (AWFen)

When we cross-tabulated this split for social class we found little difference in the percentages according to class self-perception.

|

Do you pronounce OFTEN as |

|

| AWFen |

AWFten |

Total |

| How would you characterize your social class standing? |

Poverty Level |

14 |

26 |

40 |

| Lower Middle Class/Working Class |

79 |

236 |

315 |

| Middle Class |

39 |

121 |

160 |

| Upper Middle Class/Affluent |

96 |

270 |

366 |

|

Total |

228 |

657 |

887 |

|

|

|

|

|

Do you pronounce OFTEN as |

|

| AWFen |

AWFten |

Total |

| How would you characterize your social class standing? |

Poverty Level |

35% |

65% |

|

| Lower Middle Class/Working Class |

25% |

75% |

|

| Middle Class |

24% |

66% |

|

| Upper Middle Class/Affluent |

26% |

64% |

|

|

|

26% |

74% |

|

|

|

|

|

Gender did not appear to be a factor either: the percentage of females with the AWFEN pronunciation is about the same as the percentage of males.

|

Do you pronounce OFTEN as |

|

| AWFen |

AWFten |

Total |

| What is your gender? |

Male |

69 |

178 |

247 |

| Female |

151 |

463 |

614 |

|

Do you pronounce OFTEN as |

| AWFen |

AWFten |

| What is your gender? |

Male |

28% |

72% |

| Female |

25% |

75% |

However, rural speakers appear to prefer AWFten, 82%, as compared to 65% of urban speakers and 76% of suburban speakers.

|

Do you pronounce OFTEN as |

|

| AWFen |

AWFten |

Total |

| How would you characterize your background? |

Urban |

50 |

91 |

141 |

| Rural |

26 |

115 |

141 |

| Suburban |

80 |

257 |

337 |

|

Total |

156 |

463 |

|

|

|

|

Do you pronounce OFTEN as |

| AWFen |

AWFten |

| How would you characterize your background? |

Urban |

35% |

65% |

| Rural |

18% |

82% |

| Suburban |

24% |

76% |

|

|

Finally, we looked to see what the preferences of COOP-on and CYEW-pon speakers were with respect to often and vice versa (the preferences of AWFen and AWFten speakers for the pronunciation of coupon.)

|

Do you pronounce OFTEN as |

|

| AWFen |

AWFten |

Total |

| Do you usually pronounce the word COUPON as: |

COOP-on |

150 |

363 |

513 |

| CYEW-pon |

41 |

166 |

207 |

| I pronounce it both ways |

37 |

128 |

165 |

|

Total |

228 |

657 |

885 |

|

About 10% more COOP-on speakers preferred AWFen than AWFten and 10% more AWFen speakers preferred COOP-on suggesting a clustering of the former prestige forms for some speakers.

|

Say AWFen |

Say AWFTen |

| COOP-on speakers |

30% |

70% |

| CYEW-pon speakers |

20% |

80% |

| Both |

24% |

76% |

|

Say COOP-on |

Say CYEW-pon |

Say both |

| AWFen speakers |

65% |

18% |

16% |

| AWFTen speakers |

55% |

25% |

19% |

|

|

|

|

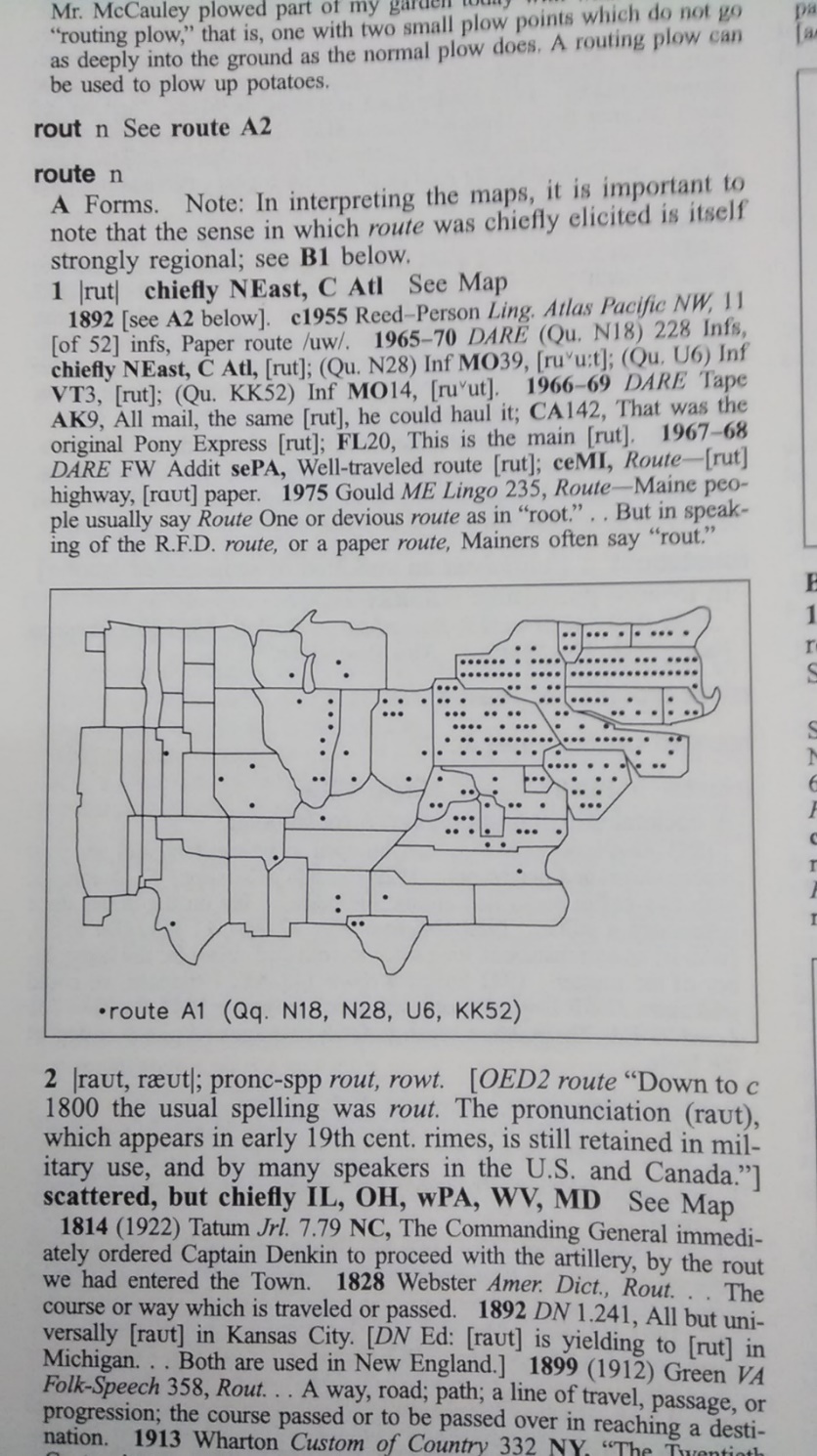

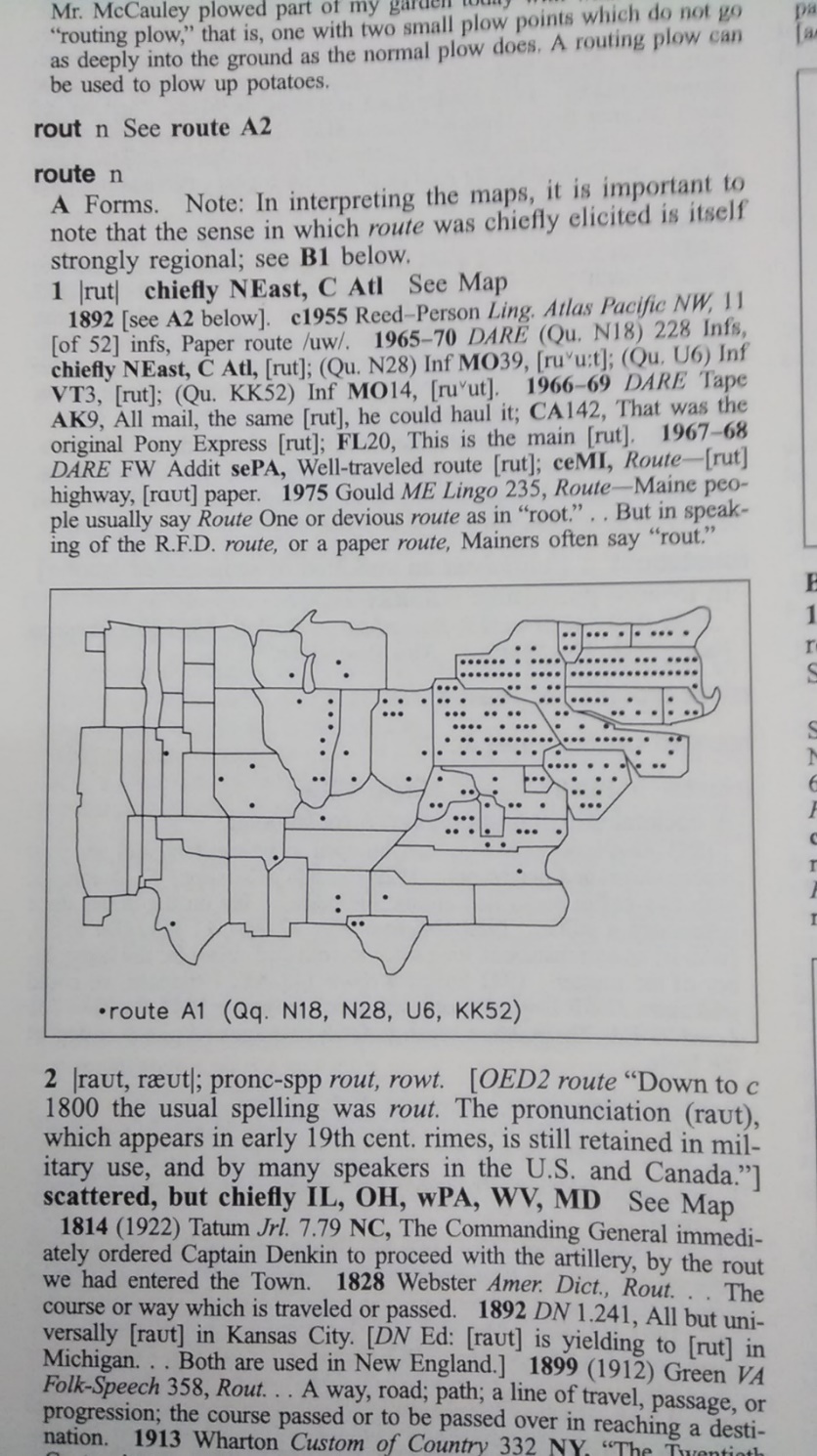

4. Two other problematic words: syrup and route

How do you say the words syrup and route? The Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) gives the pronunciation of the former as “Usu. [‘sɪrəp, sɝəp], Sth SMidl [‘sʌrəp, ‘sɝp],” noting that there is additional regional variation and evidence from spelling pronunciations. The DARE coding indicates a usual pronunciation with a high lax vowel or a mid-lax rhotic [ɝ] with somewhat different pronunciations in the South and South Midlands. Merriam-Webster offers the pronunciations [ˈsər-əp, ˈsir-əp, ˈsə-rəp] as variants and the Harvard Dialect study points to the widespread use of the variants with the [ʌ] or [ə] in the first syllable.

The various transcription systems make for a sticky situation, but the key question is whether the word is pronounced with a higher front vowel (as in SEER) or a lower more back vowel (as in SIR):

Q3 – Do you usually pronounce the word SYRUP as SIRup or SEERup?

72% reported SIRup

In American English, the word route can be pronounced as either /ru:t/ (rOOt) or /raut/ (rAWt), making the word polyphonic like economics, either, garage, and Celtic. Pronunciation may be affected by cultural influences like the iconic Route 66 and by competition from the term router for the networking device that moves data packets between computer networks. According to DARE, the usual North Eastern and Central Atlantic pronunciation is /ru:t/ with some variation in specific uses like a rural free delivery mail route or a paper route (/raut/).

DARE respondents for /ru:t/

DARE explains that the /raut/ pronunciation (they give both [raUt and [ræUt]) is “scattered but chiefly IL, OH, wPA, WV, MD.” DARE cites an Oxford English Dictionary comment that “Down to c 1800 the usual spelling was rout,” and that the pronunciation appears in 19th century still “remained in military use, and by many speakers in the U.S. and Canada.” DARE also observes that in the west, route has an additional sense in which it means the length of time working in a logging camp. Our tentative hypothesis was that westerners would prefer the /raut/ pronunciation, but also be well aware of the /rut/ pronunciation from the media. We asked

Q4 Do you usually pronounce the word ROUTE as rUWt (like boot) or rOWt (like out) or do you say both?

However, in the first two years of the survey, we forced a choice between the two pronunciations.

60% ROWT when there was a two-way choice. When there was a three-way choice, 33% reported ROWT and 42% reported pronouncing route both ways.

Add a map of route in OR & WA

5. Lexical changes in progress

We also asked about several lexical and grammatical changes in progress including the spread of gender-neutral on accident, dude, your guyses, legitly, hella and jo-jos.

5.1 on accident and by accident

If you do something accidentally, is it on accident or by accident? According to Leslie Barratt (2005), younger speakers in different parts of the country are moving toward saying on accident while older speakers tend to use by accident, a form that is still prescribed by some traditionalists. Barrett and her students studied on accident in four communities differing in size and demographics: Terre Haute, Indiana; Farmington Hills, Michigan; Irvine, California; and McRae, Georgia. Barrett’s project surveyed actual usage (with a reading passage), reported usage, and reported acceptance of the two phrases. In Indiana, for example, the use of on accident was largely nonexistent for speakers older than 30, while both by accident and on accident were used by those younger than 30. Reported use was not identical with actual use, with about 29% of those who used on accident exclusively saying that they would use by accident, a confusion which suggests that “some speakers are not aware of the form that they in fact use.” Results were similar in Michigan, California, and Georgia, though California speakers (in Irvine and Laguna Beach) showed some divergence:

While on accident occurs more frequently than by accident among the 11 and 12 year olds surveyed (22 to 13 for I did it ___ accident), it is completely absent among those surveyed over age 34. Likewise, in reported use, Californians were slightly less likely to report that they used on (21 responses) than they were to use it (26 responses). Finally, people who reported that they used by were less likely to accept on than the reverse.

Barrett concluded that on accident was found nationally among younger respondents in all four states and suggested that the use of on accident in different parts of the US dates back to at least the late 1970s. Students in our classes have sometimes proposed a distinction in the use of on and by, depending on whether the speaker is responsible or someone else is. We tested this with the following two questions, one in which contrasts a third person she with first person I:

Q11 – If your roommate does something wrong unintentionally would you say:

She did it ON ACCIDENT 65%

She did it BY ACCIDENT 11%

I could say either one 24%

Q21 – If you did something wrong unintentionally would you say:

I did it ON ACCIDENT 62%

I did it BY ACCIDENT 13%

I could say either one 24%

It seems that the proposed 1st person/3rd person split distribution is mythical rather than actual, at least in this group of respondents. Overall, younger speakers overwhelming prefer on accident and the few younger by accident speakers often report being explicitly scolded on the distinction when they had used the innovative form.

5.2 dude

If you have seen the 1969 film Easy Rider, you may recall the jail scene where the Harley-riding protagonists Wyatt and Billy find themselves in the lockup with boozy lawyer George Hanson, played by a young Jack Nicholson. When George talks the guard into giving Billy a cigarette, Billy says, “You must be some important dude. That treatment—”. Here George interrupts, “Dude? What does he mean, ‘dude’? Dude ranch?” and Wyatt explains “‘Dude’ means a nice guy, you know? ‘Dude’ means a regular person.”

The dialogue encapsulates the development of dude. The first DARE citation is an 1877 one from painter Frederic Remington who wrote fellow artist Scott Turner, with whom he was swapping sketches: “Don’t send me any more women or any more dudes.” He was referring to drawings of men and women in evening dress that Turner had been sending him. Remington said Turner should “Send me Indians, cowboys, villains, or toughs. These are what I want.”

Dude in Remington’s use means a man or boy pretentiously concerned with his clothes and grooming, as was the case for a city person new to the West, someone who might come to a dude ranch. The sense of being an out of place novice is also found in later uses in military, where dudes are new recruits. A 1936 DARE citation finds: “All right, you dudes. Fall out.”

Early on, dude could also just mean an ordinary male—a guy—and this usage picked up steam by the 1960s, according to both DARE and the OED. And along the way, dude came to be used for either sex or even for inanimate objects. From 1968, we find “When the FAC pilot gets the green light to go in he fires one of these dudes to mark the target,” and a 1985 citation is “Mom asked me and I said ‘No way, dude’.”

There’s more to the story of dude, no doubt, including its popularization by The Big Lebowski, and its emergence as a term of address. But stripped to its essentials, dude seems to have evolved from a mildly pejorative term to an neutral one and from being semantically male to increasingly generic. Our survey asked

Q12 If you use the word dude, can it refer to males or females?

Yes, it can refer to both sexes.

No, it refers only to males.

88% reported that dude can refer to both sexes. Of the 103 speakers who reported that they would not use dude generically, 76 were in the 18-29 age range. One student suggested that guys would be his preferred usage for mixed-gender groups.

We will return to the question of guys as mixed gender in section 8, along with the competing form y’all.

5.3 legit(ly)

The word legit represents a change in the part of speech as well as a clipping of legitimate. In its use as an adjective short form, Merriam Webster dates its origin to 1907 and labels it “informal.” MW also includes the adverb form, labelled as “slang,” with a first citation from 1998.

Merriam Webster doesn’t, however, include legitly, the –ly adverb. Anne Curzan, writing in her Lingua Franca column in the Chronicle of Higher Education in 2014, reports being contacted by an Michigan teacher who noted students saying things like:

“I legitly left my homework at home!”

“I legitly bombed that quiz.”

At the time, Curzan found disdain for the –ly form in both the Urban Dictionary and the popular press but concluded that “adding an –ly to legit to make a new adverb is, from a linguistic perspective, far from morphologically rebellious.”

Legit, it is worth noting, was first recorded–as a noun–in an 1897 issue of the National Police Gazette: “Bob is envious of Corbett’s success as a ‘legit.’ It pained him to see Jim strutting through four acts of a real play.” The reference is to boxer Gentleman Jim Corbett, who became an actor after his boxing career ended. The clipping legit seems to have originated in the theatre, where it meant regular, normal or standard. The OED gives a 1908 citation to “Scene shifters, stage carpenters, actors, everything and everybody strictly ‘legit’. In the early citations, the quotes indicate the novelty of the form.

We noticed the adverb uses of legit and legitly around 2013 and were curious. At first we asked about legitly, but based on feedback from students and respondents, who indicated that they used the flat adverb legit rather than the –ly form, we revised our question in year 2 of the survey.

Q16 If you are trying to explain to your friend that you really like something, would you ever say “I legit love that book.”

Yes, I can use LEGIT that way: 27%

I’ve heard this but do not use it myself: 44%

No, I do not use LEGIT this way and haven’t heard it: 28%

Based on the low numbers, it seems, however, that legit is still not quite legit.

5.4 Hella

Hella, along with its middle-school counterpart hecka, is an adverbial intensifier that apparently emerged in the 1970s Bay Area. Linguist Ben Zimmer (1986) gives an early citation from an August 1986 interview in the magazine Thrasher in which Metallica band member James Hetfield used hella twice. As youth slang, it is an index of coolness, and according to Bucholtz (2006) was “used among Bay Area youth of all racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds and both genders, much as teenagers in other parts of the United States use the intensifiers wicked and mad.” Bucholtz cited examples from a 1995-96 Bay City High School yearbook, suggesting widespread use from across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds and gender. Among them:

I love ya’ll hella tite. (African American girl)

I wont to say I had a hella fun time Playing with every one from the football team. (African American boy)

this year was hella fun! (Latina girl)

my big sista, known you for hella years, you were alwaysthere for me. (European American girl)

haven’t seen ya for hella long (European American boy)

Bucholtz saw hella as “a very stable regional marker” in the Bay area and northern California at that time with “only isolated use outside of this region.” Writing in 2006, she noted that hella “currently enjoys a much wider circulation, thanks to its occasional use in popular music, television shows, and films aimed at a youth audience … but outside California it appears to be a marked, trendy term, in contrast to its enduring use as an unmarked feature of Northern California youth speech.”

We asked our subjects:

Q15 If you are trying to explain to your friend that something is very, very good, would you ever say “That’s hella good.”

Yes, I can use HELLA that way: 57%

I’ve heard this but do not use it myself: 40%

No, I’ve never heard HELLA used this way: 3%.

From these results it is clear that hella is pervasively known (by 97% of respondents) and has clearly gained traction in the Pacific Northwest youth culture, being used by more than half.

5.5 Your guyses

Since the loss of the second person singular thee, thou, and thy/thine, the standard Written English forms have been the formerly plural forms you and your. A similar process of plural- to-singular is underway with the third person they/them/their, which is widely used as an indefinite and today is increasingly used as a singular personal pronoun as well (see Baron 2020). To attenuate the ambiguity of you in the second person, various forms have emerged that distinguish singular you from plural, such as you/y’all, you/yinz, and you/you guys. Yinz (from you ones and sometimes spelled yuns) is a regional form (DARE) while y’all has seemingly spread to a general friendly second person form. These plurals can be used in the possessive as well, giving yall’s, yinz’s, and you guys’s, and for many speakers your guys’s, with the possessive marking on both parts of the compound. Prescriptivists sometimes object to your guys. Here is Paul Brian’s view, from his Common Errors in English.

your guys’s: Many languages have separate singular and plural forms for the second person (ways of saying “you”), but standard English does not. “You” can be addressed to an individual or a whole room full of people.

In casual speech, Americans have evolved the slangy expression “you guys” to function as a second-person plural, formerly used of males only but now extended to both sexes, but this is not appropriate in formal contexts. Diners in fine restaurants are often irritated by clueless waiters who ask “Can I get you guys anything?”

The problem is much more serious when extended to the possessive: “You guys’s dessert will be ready in a minute.” Some people even create a double possessive by saying “your guys’s dessert. . . .” This is extremely clumsy. When dealing with people you don’t know intimately, it’s best to stick with “you” and “your” no matter how many people you’re addressing.

We approached your guys’s obliquely, by asking about the double possessive and giving speakers the opportunity to say that they don’t use you guys.

Q13 – If you do say “your guys’ party?” or “you guys’ party” do you pronounce it with one s or two?

I say YOU(R) GUYS PARTY: 17%

I say YOU(R) GUYSES PARTY: 56%

I might say it either way: 21%

I don’t use “you guys” or “your guys” this way: 6%

Only 6% of the respondents said they did not use possessive you guys, and the majority did report using two sibilants in the possessive. Of the 53 respondents who eschewed your guys, 39 were in the 18-29 year-old age-group and the remaining 14 were older. We have no survey data on whether speakers use you guys or your guys, though informal observation suggests that the latter predominates.

5.6 Jojos

According to local-lore and the popular press, jojos (with or without a hyphen) are a regional specialty and perhaps even an Oregon term for deep-fried, lightly breaded potato wedges. Anne Marie DiStefano, writing in The Portland Tribune in 2013, confessed to growing up in California and never having heard of jojos before moving to Oregon. She tracked the usage to the early 1960s, suggesting that “the term jojo potatoes was used widely across the country. But not universally. They also were called home fries, wedges, spuds or tater babies — and Shakey’s Pizza trademarked the term ‘mojo potatoes.’” Jojos arose from the popularity of the broaster, invented in the 1950s, which sped up the process of frying foods. According to DiStefano, the Flavor-Crisp company of Creighton, Nebraska, claims the word. She interviewed Ron Echtenkamp, retired president of a company that sold Flavor-Crisp pressure fryers, who explained that the dish arose when salespeople at a trade show used Idaho potato wedges from a nearby vendor to clean the oil in the fryer. Someone set the wedges out on the table and, according to Echtenkamp, one of the salesmen called them jojos. A similar story is told by Paul Nicewonger of Nicewonger Co., a restaurant-supply company in Vancouver, Washington. Nicewonger attributed the story of jojo being coined at a food trade show to his late father, whose company introduced the name into Pacific Northwest markets. In any case, the earliest ad found in Newpapers.com seems to be in The Evening Review (of East Liverpool, Ohio) from July 14, 1962, for Kennedy’s Restaurant in Ohio. The ad refers to Kennedy’s “New Flavor-Crisp ½ fried chicken and New jo-jo potatoes.”

Curious about the term, we included the photo below, limiting our question to jojos, steak fries, O’Briens, and potato wedges, but other terms for such fare includes the trademarked “mojos,” “tater babies” or “tater boys.”

Q22 – What name do you use for this food?

Steak Fries

JoJos

Potato Wedges

O’Briens

44% called them jojos and 43% potato wedges with another 8% opting for steak fries. Among Oregon speakers, the percentage of identifying the spuds as jojos rose to 52%.

6. Comparison with the Harvard Dialect Survey

The Harvard Dialect Survey, an online survey developed by Bert Vaux and Scott Golder consisted of 122 questions about phonetic, lexical, syntactic, and morphological differences in English in the United States. The questions were multiple-choice with a write-in option and used rhyming words to narrow the options for participants. The total number of participants was 30,788, with 385 from Oregon (1.24%) and 860 (2.78%) from Washington. Vaux and Golder’s state breakdown page gives results for 166 respondents from Oregon and 511 from Washington.

Below we consider selected results from their study.

Coupon

|

V&G (Oregon) |

V&G (Washington) |

Our results |

| as in “coop” |

56.91% |

57.89% |

58% |

| as in “cute” |

40.06% |

39.70% |

21% |

|

|

|

19% (both ways) |

The number of COOPon speakers is consistent between our 58% and their 56.91% and 57.89% results. Some of Vaux and Golder’s 40% CYEWpon speakers likely alternate.

Craig

|

V&G (Oregon) |

V&G (Washington) |

Our results |

| as in “say” |

52.63% |

59.63% |

59% (crAYg) |

| close to “say” |

22.99% |

18.55% |

|

|

|

|

|

| as in “set” |

12.47% |

13.02% |

41% (crEHg) |

| close to “set” |

11.63% |

8.18% |

|

Our two-way distinction yielded about a 60%-40% split between [e] and [ɛ] as compared to the 75.62%-24.1% and 78.18%-21.2% splits in the Harvard Dialect study.

Mary/merry/marry

|

V&G (Oregon) |

V&G (Washington) |

Our results |

| Mary & marry the same |

|

|

83% |

| all 3 are the same |

79.44% |

78.39% |

|

| all 3 are different |

2.22% |

3.13% |

|

| Mary and merry are the same; marry is different |

4.72% |

5.48 |

|

| merry and marry are the same; Mary is different |

.56% |

.63% |

|

| Mary and marry are the same; merry is different |

13.06% |

12.37% |

|

For simplicity’s sake, we assumed (based on our observations) that Mary and merry were identical for most speakers and asked only about the pronunciation of marry. Vaux and Golder’s 78-79% for all three being pronounced the same is close to our 83%. However, they found 12-13% percent of speakers reporting a Mary/marry homophony distinct from merry, which suggests that the situation is more complicated that we had anticipated.

Route

|

V&G (Oregon) |

V&G (Washington) |

Our results

(3 way) |

| rhymes with “hoot” |

17.56% |

15.13% |

25% |

| rhymes with “out” |

25.78% |

35.11% |

33% |

| either way interchangeably |

34.84% |

32.01% |

42% |

| like “hoot” for the noun and like “out” for the verb. |

16.15% |

11.78% |

|

| like “out” for the noun and like “hoot” for the verb. |

4.82% |

4.06% |

|

| other |

.85% |

1.91% |

|

Details of the percentages aside, our results and Vaux and Golder’s suggest that most speakers either alternate or prefer the ROWT pronunciation.

When we forced a two-way choice, our respondents reported using ROWT 60% of the time. We did not test for a correlation with part of speech.

Syrup

|

V&G (Oregon) |

V&G (Washington) |

Our results (2 way) |

| sear-up |

23.01% |

23.81% |

28% |

| sih-rup |

14.49% |

11.46% |

|

| sir-up |

61.36% |

63.61% |

72% |

Our results are very close to those of Vaux and Golder, assuming that their “sih-rup” group corresponds to people who opted for our “sir-up” choice.

Cot/caught

|

V & G (Or) |

V & G (Wa) |

Our results |

| Same |

87.22% |

83.67% |

82% (don/daw, hock/hawk) |

| Different |

12.78% |

16.33% |

18% |

The [a]-[ɔ] merger comes in as robust in both surveys.

You guys

Vaux and Golder also asked what words people us to refer to “a group of two or more people” with about 57% responding that they used you guys.

|

V & G (Or) |

V & G (Wa) |

| you all |

8.48% |

8.59% |

| you guys |

56.73% |

56.65% |

| You |

24.85% |

27.47% |

| y’all |

6.43% |

4.21% |

In our study, which asked If you do say “your guys’ party?” or “you guys’ party” do you pronounce it with one s or two? Only 6% of the respondents said they did not use possessive you guys. 94% responded in a way that implied use of you guys.

on accident/by accident

|

V&G (Oregon) |

V&G (Washington) |

Our results |

| by accident |

66.47% |

67.63% |

11-13% |

| on accident |

11.66% |

14.87% |

62-65% |

| Both |

18.66% |

13.97% |

24% |

There is a puzzling split between our results and those of Vaux and Golder. We found nearly two-thirds preferring on-accident while their reported results indicated the opposite.

bag, leg and egg raising

|

V&G (Oregon) |

V&G (Washington) |

| [bæg] (like “sat”) |

86.30% |

75.47% |

| [bɛg] (like “said”) |

0% |

.74% |

| [beg] (“like “say”) |

11.08% |

20.49% |

| Other |

2.62% |

3.29% |

The greater percentage of raising in Washington respondents is intriguing. We did not test for raising of [æ] in bag, though we did consider the [ɛ]-raising in egg and leg.

|

Our results |

| EGggs |

64% |

| AYggs |

36% |

|

|

| lEHgs |

62% |

| lAYggs |

38% |

Looking just at Oregon and Washington speakers, 39% of our Oregon respondents said ayggs and 42% responded that they said layggs; 37% of Washingtonians responded with ayggs and 39% with layggs.

|

Overall |

OR |

WA |

| EGggs |

64% |

61% |

63% |

| AYggs |

36% |

39% |

37% |

|

|

|

|

| lEHgs |

62% |

58% |

61% |

| lAYggs |

38% |

42% |

39% |

7. A Reading Passage

Subjects completing a survey such as ours may have misperceptions about their own pronunciation or usage, the may be unsure or guessing, they may be unduly influenced by spelling, or even misled by clumsily worded questions or transcriptions. As a check, we developed a short reading passage intended to elicit some of the Pacific Northwest distinctions we surveys as well as some others than might not be amenable to a survey method or that might be interesting for class discussion purposes. These are indicated in bold in the passage below, though of course they were not bolded in the actual reading passage. We collected 23 usable samples from speakers, most from speakers from the Pacific Northwest.

Several items in the reading passage parallel ones in the survey: Dawn, marry, Aaron, horrible, coupons, egg, legs, syrup, route, hawk, and center. The items not in the survey such as dude, food, and new reflect the /u/ and /o/ fronting found in the California Vowel Shift. The items both, wash and Washington are possible terms in which we might find an intrusive [l] or [r]. The words that and dad relate to the backing of /æ/, while menu, tent and rented to the pin-pen merger.

The repeated Thank you, thank you, thank you was an attempt to collect data on the counter-raising of [æ] and to use the allegro repetition of the phrase to induce the raising of that vowel. A few words, such as Ian and Ann, aunt, mountains, salmon, almond, greasy, poem, Saturday, and roof are indicators of dialect features not typically associated with the Pacific Northwest. Culinary and Josie were added to contrast with coupon and greasy.

Here is the passage:

Last year my friend Dawn decided to marry this dude named Ian. Both of her brothers, Aaron and Harold, helped plan the wedding menu. That was a horrible mistake.

So, the guests arrived—from Oregon, California, Washington, Idaho, Nevada, Texas, and there was even one aunt from Florida. Her Mom and Dad had arranged for the wedding to take place in a tent they rented. It was a cool setting, in a park with a view of the mountains.

Anyway, back to the food. It turned out that Aaron and Harold had gotten all the wrong food for the reception. They had supermarket coupons and bought random stuff: little hot dogs, salmon with almond sauce, milky egg salad, greasy chicken legs, and melting ice-cream cake covered with chocolate syrup. It was a culinary nightmare. Luckily Dawn’s friends Ann, Mary and Josie retraced the route to the store, and bought some real wedding food. It was a miracle that everything worked out, and Dawn’s parents just kept saying “Thank you, thank you, thank you.”

Then just as the ceremony was ending and Mary was reading a poem called “Saturday,” a red-tailed hawk swooped into the center of the tent and snagged some of the salmon. It almost got stuck under the roof but didn’t. Dawn and Ian got married and went on their honeymoon. As for Dawn’s brothers, their new job was to wash the dishes from the party.

As a check on the Qualtrix survey, we also asked the passage readers to respond to the short survey below, which was checked against their recorded pronunciations.

- How do you usually pronounce the vowel sounds in the words DON and DAWN?

the same differently

- Do you usually pronounce the word SYRUP as

SIRup SEERup

- Do you usually pronounce the word ROUTE as

rUWt (like boot) rOWt (like out)

- Do you usually pronounce HORRIBLE as

HAR-ible HOAR-ible

- Do you usually pronounce EGGS more like EHggs or AIggs

EHggs (with the EH vowel in get) AIggs (with the AY vowel in say)

- Do you usually pronounce the word COUPON as:

COOP-on CUE-pon I pronounce it both ways

- How do you usually pronounce the vowel sounds in the words MARRY and MERRY?

the same differently

- Do you pronounce THANK YOU as more like

thAHnk you (like the vowel in drank) thEHnk you (like the vowel in pen)

- Do you pronounce OFTEN as

AWFen AWFten

- Do you say the names ERIN and AARON

the same differently

- Do you pronounce the words HOCK and HAWK

the same differently

- Do you usually pronounce the word LEGS more like LEHggs or LAYggs?

LEHggs (with the vowel in less) LAYggs (with the vowel in lay) |

Comparing actual pronunciation to reported pronunciation for 23 speakers, we found that an 89% accuracy in identifying one’s own pronunciation.

8. What we learned and what’s next

8.1 Struggles

There were some rough spots. In the initial survey, we collected demographic data in a relatively open-ended fashion, asking about hometowns and parents’ hometowns, with respondents giving both leaving both gaps and giving answers like “military brat” or “moved around a lot.” We did collect zip codes, which facilitates the eventual mapping task, but we first collected age as numbers, which required us to regroup the data later to get age ranges.

Asking about social class and their perceptions of their own speech also proved to be interesting in that most self-identified as middle class and self-identified as “a better than average speaker/writer of English” (not surprising since many were English or linguistics majors). The later iterations of the survey (2015 forward) supplemented the self-identification of social class with a question about income levels, though many subjects preferred not to answer that. Later iterations of the survey also contained fewer questions, age ranges, a full list of US states and regional universities, and a question about whether hometowns were urban, rural and suburban.

We struggled with the best folk orthography for questions. From 2015 onward survey we added some homophones to the answers in the hopes that questions would be easier to follow. We initially collected data on the pronunciation of thank, but stopped because it seemed that respondents were unduly influenced toward thAHnk by orthography; only 98 responded identified thEHnk as corresponding to their pronunciation suggesting that thank might be better studied in a reading passage.

Going forward, we might drop some of the questions related to issues that seem well-resolved among young Pacific Northwesterners and add some new items, such as bag and beg, and bit and bet. The reading passage too could be simplified (respondents especially struggled with the phrase “salmon with almond sauce” and other tongue twisters that arose from our trying to do too much).

8.2 Learning opportunities

The most rewarding aspect of the research has been the way in which the work of studying data on regional speech—and their own speech—has engaged students in language study and critical thinking about language. By involving students in a local survey and discussing the issues connected to language variation and change that they can observe, we are able to engage them at several levels—as consumers of surveys and media, as thinkers about language and linguistic diversity, as speakers of a particular region, and as co-investigators in research.

The in-class discussions that arise from the survey debriefs are especially rich. Since many of the students are planning careers in fields in which they will be working with language, the survey experience gives them a first-hand look at the variability of speech and at language change in progress. Students think about their own usage, about where they came from about what has influenced their speech, and about the codes and styles that they switch into and out of. They also think about language they encounter in their lives and become curious about language and less prescriptive in their outlooks.

Various activities and discussions that can be tied to the survey questions. Here are a few we have attempted (but certainly not honed to perfection).

- Discussing the loss of the old singular second person (thee, thou, thy) forms and the re-emergence of the plural (you guys) in relation to the extension of the third person they, them, their, a topic which is on the minds of students. Discussion of pronouns can reinforce the idea that such forms have shifted for social reasons in the past.

- Introducing and critiquing the principle of “one form—one meaning” as it relates to by accident and on accident, and other terms. One reader of an early draft of this report commented that it seemed like a dumb thing for language change to create “confusing” homophones like Dawn and Don and Erin and Aaron. We have the opportunity to illustrate that the logic of language change does not always match our preconceptions of what makes sense communicatively.

- Identifying and documenting other instances of preposition variation, which tends to be less remarked upon than other types of variation (such as waiting “in line” or “on line” or getting something “on the internet” or “off the internet”).

- Taking jo-jos as the point of departure, exploring further variation among other culinary terms (including server slang, as described by Adams (2009). Students might design and administer their own food term surveys or research local eateries.

- Extending the analysis of selected terms using dictionaries and databases, such as the OED, The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) or the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA).

- Researching the history of parallels between guys and dudes, the history of guy (Metcalf 2019) and some of the contemporary criticism of the term’s use (Carey 2016, Pinkster 2018).

- Studying intensification and the emergence of hella and others forms (see for example Ito and Tagliamonte 2003).

- Introducing acoustic analysis of select vowels via Praat (Van Lieshout, 2003, Wassink 2016, Freeman 2013, 2014, Becker, et al. 2016).

- Research on local communities and on identity and affiliation, perhaps involving map tasks (Hartley 1999, Evans 2011, 2013), local history (Denham 2019), or dialect Story Maps (Szukalski and Carroll, 2019).

8.3 Next steps

What is next? We are considering relaunching the survey in the fall of 2020, perhaps inviting a wider swath of participants from Oregon, Washington, and Northern California. Along with this, we may wish to add a simplified reading passage and a (short) wordlist that can be used for acoustic analysis, and which can be recorded on a phone. Eventually, we might identify key communities in the Pacific Northwest for a comprehensive survey to be done in conjunction with presentations on dialect and linguistic diversity to include audio and video samples. An ideal next step would be an app that provided some feedback and a systematic expansion of the survey to other Oregon, Washington, and Northern California universities. We also will want to promote the work and the connection to teaching, diversity, and local history in order to generate interest in the survey from potential participants and partners.

References

Adams, M. (2009) Slang: The People’s Poetry. New York: Oxford University Press.

Al-Hatlani, A. (2019) “Potato wedge? French fry? Not quite. How the jojo became a Pacific Northwest staple.” The Seattle Times, (Aug. 7, 2019).

Bailey, G. and N. Maynor (1989) “The Divergence Controversy.” American Speech. 64: 12-39.

Barratt, L. (2005) “What Speakers Don’t Notice: Language Changes Can Sneak In.” In: TRANS. Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften. No. 16/2005. WWW: http://www.inst.at/trans/16Nr/01_4/barratt16.htm

Baron, D. (2020) What’s Your Pronoun? Beyond He & She. New York: Liveright Publishing.

Becker, K., Aden, A., Best, K., & Jacobson, H. (2016). “Variation in West Coast English: The Case of Oregon.” In Fridland, et al. eds, Speech in the Western States, 1, 107-134.

Becker, K. ed., (2019a) The Low-Back-Merger Shift: Uniting the Canadian Vowel Shift, the California Vowel Shift, and Short Front Vowel Shifts across North America. Publications of the American Dialect Society, 104 (1).

Becker, K. (2019b) “What Oregon English Can Tell Us Abot Dialect Diversity in the Pacific Northwest,” in Denham, K., ed. Northwest Voices: Language and Culture in the Pacific Northwest. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 135-150.

Bigham, D. S. (2005) The Movement of Front Vowel Allophones Before Nasals in Southern Illinois White Vernacular English (The PIN-PEN Merger). Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Texas, Austin.

Boberg, C. (2005) “The Canadian Shift in Montreal.” Language Variation and Change, 17(2): 133-154.

Boberg, C. (2008) “Regional phonetic differentiation in standard Canadian English.” Journal of English Linguistics 36, 129-154.

Bowen, W. A. (1978) The Willamette Valley: migration and settlement on the Oregon Frontier. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Brians, P. (2003) Common Errors in English Usage. Wilsonville, Oregon: William James & Company.

Brown, V. (1991) “Evolution of the merger of /ɪ/ and /ɛ/ before nasals in Tennessee”. American Speech. 66 (3): 303–15.

Bucholtz, M. (2006) “Word Up: Social Meanings of Slang in California Youth Culture”. In Goodman, J. and Monaghan, L. (eds.). A Cultural Approach to Interpersonal Communication: Essential Readings. Malden, Mass.

Bucholtz, M., Bermudez, N., Fung, V., Edwards, L., and Vargas, R. (2007) “Hella Nor Cal or Totally So Cal?: The perceptual dialectology of California.” Journal of English Linguistics, 35(4):325-352.

Butters R. R. (2001) “Data Concerning Putative Singular Y’All,” American Speech 76: 335.

Carey, S. (2016) “How Gender Neutral Is Guys, Really?” Slate.com https://slate.com/human-interest/2016/02/the-gender-neutral-use-of-guys-is-on-the-rise-but-it-s-a-slow-rise.html.

Ching, M. K. L. (2001) “Plural You/Y’All by a Court Judge,” American Speech 76: 115.

Clarke, S., F. Elms, and A. Youssef. (1995) “The third dialect of English: Some Canadian evidence.” Language Variation and Change, 7:209-228.

Conn, J. (2000) Portland Dialect Study: The story of /æ/ in Portland, Portland State University Department of Applied Linguistics MS, Oregon. Master’s thesis.

Curzan, A. (2014) “Legitly Legit.” Chronicle of Higher Education (Lingua Franca) https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/linguafranca/2014/07/10/legitly-legit/

Denham, K., ed. (2019) Northwest Voices: Language and Culture in the Pacific Northwest. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press.

Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) (1985-2013) Cassidy, F.G. & Hall, J.H. (Eds.). Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Dinkin, A. (2005) “Mary, darling, make me merry; say you’ll marry me: Tense-lax neutralization in the Linguistic Atlas of New England.” U. Penn Working Papers in Linguistics 11.2: Selected Papers from NWAV 33, ed. S. E. Wagner, 73–90.

DiStefano, A.-M. (2013) “Restaurants add another chapter to jojos’ long history,” The Portland Tribune, https://pamplinmedia.com/pt/11-features/155981-restaurants-add-another-chapter-to-jojos-long-history.

Esling, J. and H. Warkentyle. (1993) “Retraction of /æ/ in Vancouver English.” In Focus on Canada, ed. S. Clark, 229-246. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Company.

Evans, B. (2011) “‘Seattletonian’ to ‘Faux Hick’: Perceptions of English in Washington State.” American Speech, 86(4):383-414.

Evans, B. (2013) “‘Everybody sounds the same:’ Otherwise overlooked ideology in perceptual dialectology.” American Speech, 88(1):62-80.

Foster, D. W. and R. J. Hoffman (1966) “Some Observations on the Vowels of Pacific Northwest English (Seattle Area)” American Speech, 41(2): 119-122.

Freeman, V. (2013) “Bag, beg, bagel: Prevelar raising and merger.” Master’s thesis, University of Washington.

Freeman, V. (2014) “Bag, beg, bagel: Prevelar raising and merger in Pacific Northwest English.” University of Washington Working Papers in Linguistics, 32. Seattle, WA: Linguistics Society at the University of Washington.

Fridland, V., T. Kendall, B. E. Evans and A. B. Wassink, eds. (2016) Speech in the Western States: volume 1, The Coastal States. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Fridland, V., A. B. Wassink, T. Kendall, and B. E. Evans, eds. (2017) Speech in the Western States: volume 2, The Mountain West. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Garner, B. (1998) Garner’s Modern English Usage. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gordon, M. J., (2008) “New York, Philadelphia, and other northern cities: Phonology.” Varieties of English, 2, 67-86.

Hartley, L. C. (1999) “A view from the West: Perceptions of U.S. dialects by Oregon residents.” In Handbook of Perceptual Dialectology, ed. D. R. Preston, 315-332. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hinton, L., B. Moonwoman, H. Luthin, M. Van Clay, J. Lerner, and H. Corcoran. (1987) “It’s not just the Valley Girls: A study of California English.” Proceedings of the Thirteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 117-128.

Ito, R. and S. Tagliamonte. (2003) “Well Weird, Right Dodgy, Very Strange, Really Cool: Layering and Recycling in English Intensifiers.” Language in Society 32(2): 257-‐79.

Kennedy, R. and Grama, J. (2012) “Chain shifting and centralization in California vowels: An acoustic analysis.” American Speech, 87(1):39-56.

Koops, C., E. Gentry, and Pantos, A. (2008) “The effect of perceived speaker age on the perception of PIN and PEN vowels in Houston, Texas.” University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 14(2), 12.

Kretzschmar, W. A., (2008). “Standard American English pronunciation.” Varieties of English, 2, 37-51.

Kuhlman, P. (2000, January, 18) Online posting “Re: on accident.” ADS-L archived at http://listserv.linguistlist.org/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind0001C&L=ADS-L&P=R2805&I=-3.

Labov, W., S. Ash, and C. Boberg. (2006) The Atlas of North American English: Phonetics, Phonology, and Sound Change. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Loy, W. G., S. Allan, J. E. Meacham, and A. R. Buckley. (2001) Atlas of Oregon. Eugene: University of Oregon.

Luthin, H. W. (1987) “The story of California (ow): the coming-of-age of English in California.” In Variation in Language: NWAV-XV at Stanford, ed. K. M. Denning et al., 312-324. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Department of Linguistics.

Maynor, N. (1996) “The Pronoun Y’all: Questions and Some Tentative Answers.” Journal of English Linguistics, 24(4): 288–294.

Metcalf, A. (2019) The Life of Guy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mitford, N. (ed.) (1956) Noblesse oblige. London, Hamish Hamilton.

Mills, R. V. (1950) “Oregon Speechways,” American Speech, 25(2): 81-90.

Modern Language Association. The MLA Language Map Data Center. Retrieved from https://apps.mla.org/cgi-shl/docstudio/docs.pl?map_data_results.

O’Conner, P. T. and S. Kellerman (2010). “Is ‘legit’ legitimate?” The Grammarphobia Blog https://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2010/06/is-legit-legitimate.html

Pinsker, J. (2018) “The Problem With ‘Hey Guys’” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2018/08/guys-gender-neutral/568231/

Pronunciation of Aaron vs. Erin: Ask a linguist. (2007) The Linguist List.org. https://linguistlist.org/ask-ling/message-details1.cfm?asklingid=200384213

Reed, C. (1952) “The pronunciation of English in the state of Washington.” American Speech, 27(3):186-189.

Reed, C. (1961) “The pronunciation of English in the Pacific Northwest.” Language, 37(4):559-564.

Richardson G. (1984) Can Y’all Function as a Singular Pronoun in Southern Dialect? American Speech, 59 (1): 51-59.

Ross, A. S. C. (1954) “Linguistic class-indicators in present-day English,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 55, 113–149.

Spencer, N. J. (1975) “Singular Y’all,” American Speech 50: 315

Strelluf, C. (2018) Speaking from the heartland: The Midland vowel system of Kansas City: Durham, NC, Duke University Press.

Szukalski, B. and A. Carroll (2019) The Myriad Uses of StoryMaps. Arcgis.com. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/1b38cf02f39849478d3123dcd9465022

Tillery, J. and G. Bailey (1998) “Yall in Oklahoma,” American Speech 73: 257.

Thomas, C. K. (1958) Introduction to the phonetics of American English. New York: Rondal Press Company.

van Lieshout, Pascal (2003) Praat: A Short Tutorial. https://web.stanford.edu/dept/linguistics/corpora/material/PRAAT_workshop_manual_v421.pdf

Vaux, B., and S. Golder (2003) The Harvard dialect survey. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Linguistics Department.

Ward, M. (2003) Portland Dialect Study: The fronting of /ow, u, uw/ in Portland, Oregon. Master’s thesis. Portland State University. Conn, Jeff. (2000) Portland Dialect Study: The story of /æ/ in Portland, Portland State University Department of Applied Linguistics MS, Oregon. Master’s.

Wassink, A. B. (2015) “Sociolinguistics patterns in Seattle English.” Language Variation and Change 27:31-58.

Wassink, A. B. (2016) The Vowels of Washington State. Publication of the American Dialect Society 1; 101 (1): 77–105.

Wassink, A. B. (2019) “English in the Evergreen State,” in Denham, K., ed. Northwest Voices: Language and Culture in the Pacific Northwest. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 95-116

Zimmer, B. (1986) [Ads-l] hella (Aug. 1986) http://listserv.linguistlist.org/pipermail/ads-l/2016-March/141400.html

[last rev. 7/22/2020]

The Indian Bride by Karen Fossum

The Indian Bride by Karen Fossum

Follow

Follow

Kylan de Vries & Carey Sojka: We are always so appreciative and honored by the openness of our participants in sharing aspects of their lives with us, basically strangers. Many of our participants asked to stay in touch with us and want to know about what we publish from our interviews with them. I think for Kylan, it was reaching out to participants after 15 years and reinterviewing some of them that was such a surprise. What an amazing experience to hear about how their lives had changed over that time!

Kylan de Vries & Carey Sojka: We are always so appreciative and honored by the openness of our participants in sharing aspects of their lives with us, basically strangers. Many of our participants asked to stay in touch with us and want to know about what we publish from our interviews with them. I think for Kylan, it was reaching out to participants after 15 years and reinterviewing some of them that was such a surprise. What an amazing experience to hear about how their lives had changed over that time! Gobsmacked! The British Invasion of American English by Ben Yagoda.

Gobsmacked! The British Invasion of American English by Ben Yagoda.  Play It Again Sam: Repetition in the Arts by Samuel Jay Keyser

Play It Again Sam: Repetition in the Arts by Samuel Jay Keyser Amity: A Novel by Nathan Harris

Amity: A Novel by Nathan Harris Red Hook and Londongrad by Reggie Nadelson

Red Hook and Londongrad by Reggie Nadelson Lethal Prey by John Sanford

Lethal Prey by John Sanford

PC: Yes! According to grounded cognition, we are always simulating experiences through multiple modalities in the brain—for vision, muscle movement, smell, sound, etc. The benefactor practice draws on this natural capacity as well, to simulate experience of care from our past so as to relive them in the present throughout the body. This is happening while reading, too. Some fascinating research has shown that reading fiction in particular can help increase empathy because it involves simulating the experiences of diverse others. Fictional characters can also serve as benefactors by helping to work out various dilemmas or difficulties we might be facing. They can help us to be seen through their experience and inspire us in our own journeys. I recently read John Ciardi’s translation of Dante’s Inferno and found that experience to be deeply inspiring for contemplations of suffering and navigating challenges in our world.

PC: Yes! According to grounded cognition, we are always simulating experiences through multiple modalities in the brain—for vision, muscle movement, smell, sound, etc. The benefactor practice draws on this natural capacity as well, to simulate experience of care from our past so as to relive them in the present throughout the body. This is happening while reading, too. Some fascinating research has shown that reading fiction in particular can help increase empathy because it involves simulating the experiences of diverse others. Fictional characters can also serve as benefactors by helping to work out various dilemmas or difficulties we might be facing. They can help us to be seen through their experience and inspire us in our own journeys. I recently read John Ciardi’s translation of Dante’s Inferno and found that experience to be deeply inspiring for contemplations of suffering and navigating challenges in our world. King of Ashes by S. A. Cosby

King of Ashes by S. A. Cosby

Win by Harlan Coben

Win by Harlan Coben The Real-Town Murders by Adam Roberts

The Real-Town Murders by Adam Roberts

MARCIE R. RENDON: The first publisher of Murder on the Red River and Girl Gone Missing was Cinco Puntos Press. They sold their publishing company to Lee and Low Publishers, which focuses on children’s lit by folks of color. Cash Blackbear drinks beer and smokes cigarettes so I secured an agent (Jacqui Lipton) and she was the one who negotiated the series going to Soho Press. And they have published Sinister Graves and the most recent release, Broken Fields. We seem to be a good fit for each other.

MARCIE R. RENDON: The first publisher of Murder on the Red River and Girl Gone Missing was Cinco Puntos Press. They sold their publishing company to Lee and Low Publishers, which focuses on children’s lit by folks of color. Cash Blackbear drinks beer and smokes cigarettes so I secured an agent (Jacqui Lipton) and she was the one who negotiated the series going to Soho Press. And they have published Sinister Graves and the most recent release, Broken Fields. We seem to be a good fit for each other.

Read this one for my book club. It’s an intriguing true crime story ripped from the headlines of the 1950s. Clark is somewhat clunk as a writer–often interjecting herself into the story for no reason–but she’s done a fine job of researching the history of the Barbara Graham case and has a good eye for interesting historical details.

Read this one for my book club. It’s an intriguing true crime story ripped from the headlines of the 1950s. Clark is somewhat clunk as a writer–often interjecting herself into the story for no reason–but she’s done a fine job of researching the history of the Barbara Graham case and has a good eye for interesting historical details.

Sweet Vidalia by Lisa Sandlin

Sweet Vidalia by Lisa Sandlin Down Cemetery Road by Mick Herron

Down Cemetery Road by Mick Herron

ME: The thing we call his first word is “round-round,” which he used to describe a ceiling fan. It was immensely important at the time because it resolved itself out of his babbling. Which is to say, he was vocalizing repeatedly, then my attention shifted a bit, which is when I realized he was trying to tell me something. I repeated the word, and he responded happily to my recognition.