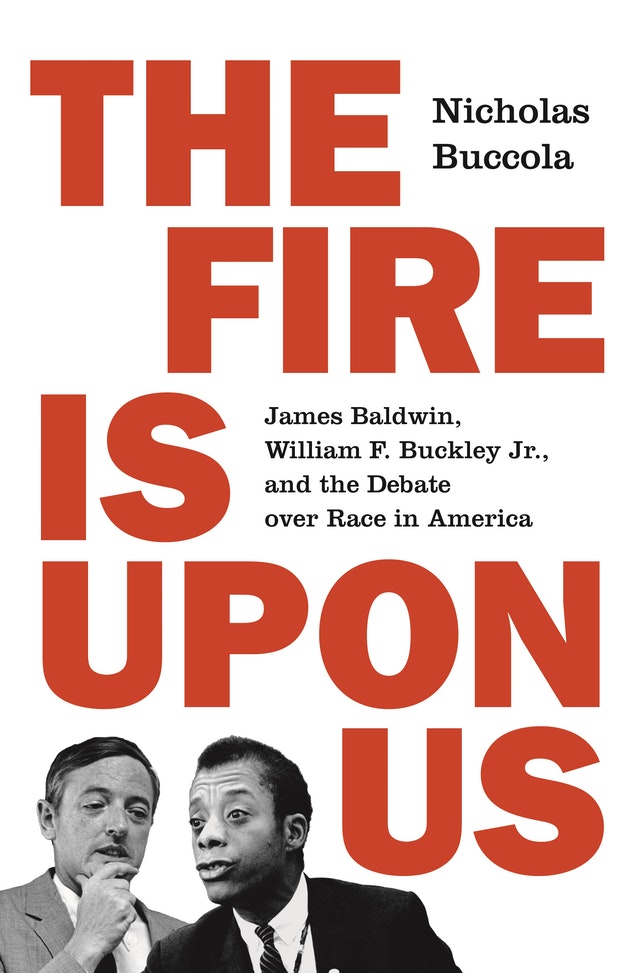

Nicholas Buccola is a writer specializing in American political thought. His book, The Fire Is upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate over Race in America (Princeton University, 2019) was the winner of the 2020 Oregon Book Award for General Nonfiction.

Nicholas Buccola is a writer specializing in American political thought. His book, The Fire Is upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate over Race in America (Princeton University, 2019) was the winner of the 2020 Oregon Book Award for General Nonfiction.

Buccola has MA and PhD degrees from the University of Southern California and his work has appeared in The New York Times, Salon, The Oregonian, Dallas Morning News, Baltimore Sun, Dissent and Reason.

He is also the author of The Political Thought of Frederick Douglass: In Pursuit of American Liberty (New York University Press, 2012) and the editor of The Essential Douglass: Writings and Speeches (Hackett, 2016) and Abraham Lincoln and Liberal Democracy (University Press of Kansas, 2016).

Ed Battistella: Congratulations on the Oregon Book Award and all the other accolades The Fire is Upon Us is receiving. I really enjoyed the book. What motivated you to dig into the lives of the lives of Baldwin and Buckley so deeply?

Nicholas Buccola: Thank you so much, Ed. I was really honored to see The Fire Is Upon Us (Fire) honored along so many great books (including yours). Many years ago, I watched the BBC recording of the 1965 Cambridge debate between Baldwin and Buckley and I became transfixed. It was such a dramatic and important moment. At the high tide of the civil rights movement and on an international stage, you have “the poet of the civil rights revolution” (as Malcolm X described Baldwin) and “the Saint Paul of the conservative movement” (as one of Buckley’s biographers described him) debating race and the American dream. The debate itself struck me as historically and politically compelling and as I dug into the archives, I soon realized that I had a much longer story to tell. Baldwin and Buckley were almost exact contemporaries – born in the same city, in fact – and the “backstory” of their life experiences and intellectual biographies proved to be the heart of the book. By weaving their stories together, I hope the book reveals things that might be missed otherwise.

EB: A striking moment for me was the debate that involves Baldwin and Malcolm X and the emphasis on identity as living free of myth and ideology. Would you say that is central to Baldwin’s message?

NB: Yes, I see that as one of Baldwin’s key insights. Time after time, Baldwin explained that what concerned him most were “grave questions of self” or “questions of identity” and how those questions were related to the human quest for freedom and fulfillment. Baldwin’s basic idea was that human beings construct their identities in ways that they think will make them feel safe. One of the primary ways we tend to do this, Baldwin argued, is by relying on the idea of status; by trying to figure out ways to feel superior to others. Ideologies of exclusion and inhuman ways we treat one another – large and small – have their roots in this desire for safety. As Baldwin often said, the roots of racism are within the racist, not within the object of his hatred. The same is true of homophobia, xenophobia, transphobia, and so on. Baldwin did not think any of us would wake up one fine day and fully liberate ourselves from the myths and ideologies by which we live. But he did call on all of us to engage in the sort of ruthless introspection each day that might allow us to treat ourselves and each other with greater dignity than we might otherwise.

EB: Reading some of the arguments that Buckley and others made about stability, protest, Western culture, and limiting voting, it’s hard not to see their echoes today. Is Buckley really the key figure in American conservative movement?

NB: Many readers have been struck by the parallels between the ideas Buckley developed and popularized and the contemporary American Right. I try to be careful about overstating Buckley’s importance and making overly bold causal claims about the connections between his ideas and actions and the political world we see. With that caveat, I do argue in the book that Buckley played an outsized role in American political culture. He edited the country’s most important conservative magazine (National Review), he had a syndicated newspaper column published thrice weekly in over one hundred newspapers, he was on the road speaking forty weeks of the year, he was a constant presence on radio and television, he had the ear of many leading conservative politicians, and he played a key role as a kind of “gatekeeper” and organizer in the conservative movement. From this position of considerable influence, Buckley had a great deal of influence. In the book, I provide a deep dive into his racial politics and surrounding issues and many readers have found plenty of reason to credit (or blame) Buckley for some of what we see on the contemporary American Right.

NB: Many readers have been struck by the parallels between the ideas Buckley developed and popularized and the contemporary American Right. I try to be careful about overstating Buckley’s importance and making overly bold causal claims about the connections between his ideas and actions and the political world we see. With that caveat, I do argue in the book that Buckley played an outsized role in American political culture. He edited the country’s most important conservative magazine (National Review), he had a syndicated newspaper column published thrice weekly in over one hundred newspapers, he was on the road speaking forty weeks of the year, he was a constant presence on radio and television, he had the ear of many leading conservative politicians, and he played a key role as a kind of “gatekeeper” and organizer in the conservative movement. From this position of considerable influence, Buckley had a great deal of influence. In the book, I provide a deep dive into his racial politics and surrounding issues and many readers have found plenty of reason to credit (or blame) Buckley for some of what we see on the contemporary American Right.

EB: I enjoyed the way you brought out the parallels between Buckley and Baldwin and the use of the alternating narratives. Was it difficult to keep the two in balance?

NB: Yes and no. I feel incredibly fortunate in the sense that the material really told me how to tell the story. The fact that Baldwin and Buckley were almost exact contemporaries made the “parallel lives” approach look rather well. And I was also fortunate that both men were compelling characters who led lives that were not only interesting, but also lives at the center of their respective movements. They were both so prolific as public and private writers so I felt like I could glimpse into their minds almost every day as they were living through and shaping this history. On the question of “balance,” there were moments when that was challenging. If, for example, one character had an especially interesting year while the other did not, I had to come up with ways of altering my “weave” technique to tell the story in the most compelling way. Sometimes that meant I would stick with one character a bit longer before switching back to the other a bit later in the timeline. I never had a real formula in mind. I did not, for example, track how many pages I was writing about Baldwin and then try to give Buckley “equal time.” I let the material guide me. In the end, I feel good about where we ended up. It’s a weighty book and earlier drafts were even weightier. I am grateful to my editor, Rob Tempio, and peer reviewers for helping me find places to trim.

EB: I hope you’ve had an opportunity to teach some of the material from the book, and I wonder what the reaction of today’s student is to the issues of the 1960s?

NB: I have had the opportunity to teach some of this material. I was able to teach a seminar on Baldwin and Frederick Douglass and it was the most extraordinary teaching experience of my life. Although the class was about two figures I have studied for a long time, it was probably the course in which I did the least amount of talking. The students were so engaged with these wonderful writers, so I got to sit back and listened to their brilliance for a few hours a week. What a joy. Baldwin’s words strike the students as so prophetic and urgent. I am now teaching him in my Introduction to Political Theory class (“Great Political Thinkers”) because I think he belongs right there alongside Plato and the other major thinkers. I think today’s students are fascinated by the politics and culture of the 1960s. Especially in the last year or so, they sense that they are living in a world in which the political culture is undergoing some major shifts. They see there is much to learn from other moments in which the ground was shifting beneath the feet of the culture.

EB: If Baldwin and Buckley were magically transported to the present, what do you suppose they would say?

NB: Oh wow. There’s a thought! They were both remarkably consistent as thinkers so I do not imagine their political philosophies would have changed very much as a result of the things that have happened since each man died (Baldwin in 1987 and Buckley in 2008). While I think Baldwin had the same moral lodestar throughout his life – the idea that we ought to pursue the conditions under which each human being can be free and find fulfillment – I think time did radicalize his thinking on how this might be achieved. Baldwin was always suspicious of ideologies and oversimplification so I resist the idea that he would fit neatly into one of our political boxes. But I do think he would call on us to think through the radical implications of the moral idea that each human being has the right to live in a world in which their dignity is respected and protected. That world is not this world and we have a long way to go. On the other side of the story, it would have been fascinating to see how Buckley would have navigated the Trump era. On the one hand, he did not like Trump personally and I think he would have been critical of Trump’s disdain for norms, institutions, and the rule of law. On the other hand, I think it is clear that he would have liked a great deal about Trump’s politics. Buckley was no stranger to the politics of racial resentment that was so key to Trump’s rise and he was, in fact, one of its architects and promoters. And he probably would have also been tempted – as so many conservatives were – to put up with Trump because he appreciated some of the outcomes he delivered (e.g., tax cuts, conservative judges, etc.) If you figure out how to magically transport them back, please let me know. I have some questions. Drinks are on me.

EB: How did writing the book change you as a writer and scholar? What’s next for you?

NB: This book has been a transformative experience for me in so many ways. Everything I had written before this was really for an academic audience of fellow “experts” or “insiders.” When I started doing the research for the book, I knew I could write another book like that, but I also knew I shouldn’t write another book like that. It was tempting to stick with what I knew how to do, but the material was pushing me in this other direction. What I had in front of me was a compelling story that was historically important and politically urgent. My job was to tell this story. This meant abandoning most of the forms and techniques of my training as a political theorist. But once I got in the groove, I never looked back and I don’t know if I ever will. I am still doing political theory (or political philosophy), which is, at its core, about asking big questions about how we ought to live together. I am going to keep doing that, but my primary method will be to address those big questions by way of (hopefully) compelling narratives.

Nowadays, I am at work on another book that looks at the same era I examined in Fire but from a different angle. As I worked on this book, I was struck time and again by the use of “freedom” or “liberty” by both the civil rights revolutionaries and the conservative counterrevolutionaries. These groups were both operating under banners of freedom, but they were viewing each other with suspicion and often downright hostility. I am using the “weave” technique once again to figure out what we can learn about the meaning of freedom – a concept we are still arguing about – by thinking about these two movements together. Who knows, this may be the second book in a trilogy about this era. We’ll see. The good news is I’ve never loved writing more than I do now and I think these stories are urgent for our politics.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

NB: Thanks so much for the opportunity. These are great questions and I look forward to visiting Ashland to talk about the book!

Follow

Follow