NICOLE WALKER’s books include After-Normal: Brief, Alphabetical Essays on a Changing Planet and Sustainability: A Love Story and Quench Your Thirst with Salt. Her work has been published in Orion, Boston Review, Creative Nonfiction, Brevity, and The Normal School and has appeared in multiple editions of Best American Essays.

NICOLE WALKER’s books include After-Normal: Brief, Alphabetical Essays on a Changing Planet and Sustainability: A Love Story and Quench Your Thirst with Salt. Her work has been published in Orion, Boston Review, Creative Nonfiction, Brevity, and The Normal School and has appeared in multiple editions of Best American Essays.

Walker grew up in Salt Lake City, Utah and earned a BA from Reed College and both an MFA and a PhD from the University of Utah. Today she is a professor at Northern Arizona University in where she directs the MFA and a recipient of a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts

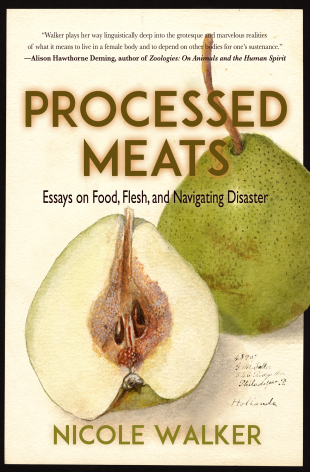

Her most recent book is Processed Meat: Essays on Food, Flesh, and Navigating Disaster, available from Torrey House Press.

You can find Nicole Walker’s website here.

Ed Battistella: I really enjoyed the essays in Processed Meats. Can you tell us a little about the title of the collection?

Nicole Walker: The book went through many title drafts: Salmon of the Apocalypses and Canning Peaches for the Apocalypse were among the two, but the apocalypse theme seemed to hit a little too close to home once the pandemic started. A pandemic isn’t quite an apocalypse, but making light of apocalypse when so many people were suffering felt offkey. The phrase “processed meats” covers so many aspects of the book—the way that so much food is processed and served in the U.S., the way raising children in a culture with so much conflicting advice feels like we process our kids as much as help them grow, the way so much of that advice is afflicted upon women for how to eat and cook and live. But there’s also the philosophical angle to the book that suggests we process our traumas and disasters by working through them, by being patient. That work and patience is akin to cooking—the small measures we take to get through the day are the energies that help of process those harder times.

EB: Processed Meats is very much a pandemic book. How did the pandemic affect you as a writer?

NW: I know a lot of people had a hard time writing during the pandemic, but, just like cooking, writing helps me process hard things. I wrote a lot. This spring, while teaching, I assigned myself 1000 words a day for a novel I’m working on. There’s something about being trapped at home that is very helpful to getting work done. I think of Salinger and how he was such a recluse. Of course, as far as we know, he didn’t write much in his most reclusive years. A writer needs some balance between real life and brain or it’s all just brain food and that’s only good for zombies. As we’ve begun to poke our heads back into the world, I’ve noticed how thirsty I’ve been just to drink in the presence of other humans. Zoom offers a lot of benefits but observing human behavior in its natural environment is not one of them. Everyone is weird on zoom. They’re weird in real life too but in a less self-conscious way.

The book went through a substantial reworking. Although disaster was always a primary theme of the book, immediate disaster wasn’t the central theme. I am grateful I had the chance to recast the book to touch on something we all shared. Individual disasters matter but a collective disaster made an impact on all of us. I weirdly feel honored to have had a chance to talk about that impact.

EB: The subtitle is “Essays on Food, Flesh, and Navigating Disaster” What is the relation between food and disaster—and coping?

NW: You anticipated my earlier answer! I spend a lot of time thinking about valences of words. “Coping” is exactly what we do when we try to navigate disaster. You put one food in front of the other. You chop one more onion. You make meal after meal and clean kitchen after kitchen until at some point, coping isn’t just coping, it’s living. Coping and living are two sides of the same coin. Once you start dancing in the kitchen, you know which you’re doing.

EB: Several of the pieces are about the body in sickness and wellness. Should we be thinking about food and health more? Differently?

NW: Just as with raising kids, there is so much advice on how to do it ‘right.’ Eggs are bad. Then good. Then bad again. I think they’re back to being good for you. But, because we are often far flung from our families and traditions, we have to rethink everything we do and everything we eat. It can be exhausting. But it can be good too. There’s something to be said for considering every choice and thinking through is this healthy for my body, for the planet, for my kids. Raising kids and feeding them are nearly synonymous, at least in the early years. They say that choosing what to eat is the only choice little kids get. I try to read as much as I can about nutrition and agricultural effects on the environment. Then, I like to give my kids as many options as possible within that research. More is better with both research and choice and I believe in people’s right to choose with enough research. So, I guess this is a very complicated answer to your question but Processed Meats provides some of the science behind our eating and agricultural habits. It doesn’t aim to be didactic. It says, now that you know the consequences of what you’re choosing to eat (and do and drive), choose well.

NW: Just as with raising kids, there is so much advice on how to do it ‘right.’ Eggs are bad. Then good. Then bad again. I think they’re back to being good for you. But, because we are often far flung from our families and traditions, we have to rethink everything we do and everything we eat. It can be exhausting. But it can be good too. There’s something to be said for considering every choice and thinking through is this healthy for my body, for the planet, for my kids. Raising kids and feeding them are nearly synonymous, at least in the early years. They say that choosing what to eat is the only choice little kids get. I try to read as much as I can about nutrition and agricultural effects on the environment. Then, I like to give my kids as many options as possible within that research. More is better with both research and choice and I believe in people’s right to choose with enough research. So, I guess this is a very complicated answer to your question but Processed Meats provides some of the science behind our eating and agricultural habits. It doesn’t aim to be didactic. It says, now that you know the consequences of what you’re choosing to eat (and do and drive), choose well.

EB: You talk about some your past food experiences. What food lore do you want to pass on?

NW: Most of my food lore is about growing food more than cooking it. My mom always told me to plant peas in February. Usually, I forget. Who thinks about gardening in February? But I remembered this year and now, after snow, wind, deep freeze, the peas are going strong. My mom also said to pinch off early flowers from tomatoes so the energy can go into the plant. And then, when you have a lot of tomatoes, pinch off some of the flowers still so the energy can go into ripening the fruit you already have.

Also: use a lot of butter. My daughter cooks eggs in a pan without using any fats at all. I have to scrub that pan. Also, butter is delicious.

EB: For you, what is the best thing about food?

NW: The idea of abundance. I love going to the CSA (community supported agriculture), picking up my vegetables, laying them out on the table, cutting the tops off the beets, putting the greens in the fridge, roasting the roots. I love it when there are seven fresh carrots laid upon the table. I also love that, when I turn around, five of them are gone because my kids love fresh carrots. They like old carrots too but fresh carrots go quickly around here.

EB: What’s the worst thing?

NW: While there is sometimes an abundance of delicious vegetables, there’s often a scarcity of ideas of what to cook. I hate running out of ideas of what to make for dinner. As the end of the book articulates, chicken, chicken, chicken becomes the go-to and stand-by and the distinctly uninspired. We eat a lot of chicken and carrots. Sometimes, I run low on ideas for what to make because my kids don’t always love the same thing as the other. Sometimes, I’m just busy and what? There’s more chicken? Whoohoo. I hate the thought of going to the store too for one ingredient that a fancy new recipe has. But, after reading Tod Davies’ Jam Today and talking with her about Processed Meats, I remembered that shooting for culinary perfection is its own flaw. So, when I made asparagus soup but had not the sorrel the recipe called for, I used dandelion leaves, which I had in abundance reminding me that looking for what is abundant around you instead of searching out that which is scarce is the key to happiness.

EB: Can you tell us about some of the other projects you are working on?

NW: One of the things I mentioned above was some of the difficulties of families being far flung. I’m working on a book about how home shapes the kind of climate change future we see and how we cope with the effects of climate change and how loss of homes uproots us from that connection to land. Some of the essays have titles like “How to Be Happy When Your Favorite Tree Is Dying” and “Effluent: What Can We Do with All this Human Waste.” I try to be realistic about climate change and things like “going home.” That realism sometimes leads to hard reflection. It also sometimes leads to absurd realizations. I like the idea that even when confronted with hard things, we can cope with them with humor, as well as with delicious foods.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

NW: Thank you so much, Ed! I loved these questions and had fun answering them. I’m so grateful to you for reading and talking about Processed Meats!

Follow

Follow