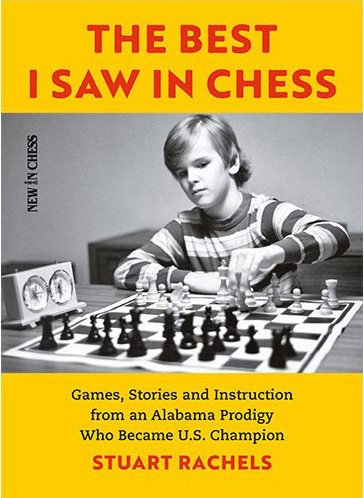

Born in 1969, Stuart Rachels grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, and began playing chess when he was 8. At 11 he became a chess master and was the US Junior Champion in 1988 and the US co-champion in 1989. At the age of 23, he retired from competitive chess.

A former Marshall Scholar, he has a PhD in Philosophy from Syracuse University and teaches at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. This year he published The Best I Saw in Chess (New in Chess, 2020).

Ed Battistella: When you were not quite 12, you became the youngest chess master in US history. How did you learn to play and how did you get so good so fast?

Stuart Rachels: My brother David taught me the rules. I have no idea how I got good. It was just something my brain took to. It was also my most enjoyable period as a player. Getting good is more fun than being good.

EB: Reading The Best I Saw in Chess, it occurred to me that good chess books are equal parts narrative and analysis. Did you think about this balance as you were writing the book? Or think about the memoir genre more generally?

SR: Yes and yes. Here are some tips I gave myself. (i) In telling stories, just say what happened. Don’t give commentary. Commentary is boring, and anyway your readers will prefer their own interpretations, so don’t waste their time giving them yours. (ii) In writing your life story, don’t start with your birth and end with you sitting there writing your life story. Skip around in time. (iii) Autobiographical writing is about taming one’s ego. Write a lot of drafts; take a lot of time to gain perspective. (iv) Chessplayers don’t want to hear your life story. They want to see cool moves. Make it less about you. Every story you tell, you must earn with cool chess moves. (v) Don’t make yourself look good; let yourself look human. Aside from Bobby Fischer, Mikhail Tal was the best blitz player in the world during the 1960’s. Yet when Tal recounts a blitz tournament in his autobiography, the only position he gives is one in which he made a silly blunder. Does this make you think less of Tal? Not at all; just the opposite. (vi) Your main obligation is to your reader, not to yourself. Don’t suppress uncomfortable truths. They’re uncomfortable for you, not for your reader. And though you hate it, include games that you lost. Guess what? Some of the coolest moves you’ve ever seen were ones that kicked your butt.

EB: What was the toughest part of writing The Best I Saw in Chess?

SR: Finding the right title. Stuart Rachels’ Chess Career is too conceited. Also, the book is primarily about chess, not about me; it is a book of instruction, where the lessons come from my games. So the title should not cry out “autobiography.” Yet it shouldn’t ignore that element; How to Think about Chess Positions isn’t right, either. And the title should contain the word ‘chess.’ Also, it should say something about me, because, who am I?—I haven’t played chess in 25 years. (I covered that desideratum with a self-promoting subtitle.) It took me months to find a title I was happy with.

EB: This is one of the few chess books I’ve seen that has footnotes, which I think is great. What does your chess library look like?

SR: Disorganized. I’ve acquired so many chess books in the last few years that they’ve outgrown their bookshelf, and now that I’m writing another book (about fortresses), my books tend to wind up in stacks, relating to some theme. Footnotes are important. I use them for references and for jokes.

EB: Who are some of the best chess writers out there? Do they have anything in common?

SR: I was trying to combine the virtues of John Nunn and Mikhail Tal. Nunn explains chess ideas perfectly (accurately, succinctly, insightfully), but he displays no personality—no humor and nothing too personal. Meanwhile, Tal has never edited a sentence in his life (he dictated his books, and it shows), but his wit, affable nature and lack of pretension are manifested on every page.

EB: You mention that you don’t always calculate a lot of variations, but also that you sometimes run into time trouble. Can you say anything about your thought process during a game?

SR: My trainer once told me that I would get into time trouble even if I began the game with five hours on my clock. There’s always lots to think about, but my time mismanagement probably derived from my neuroses—a useful neurosis. I was always motivated by the fear that I was about to make a bad move. This anxiety helped me focus, but it also slowed me down. … As for my thought process, I’ll just mention the only thing which (I think) was unusual. Often, there would be the move I wanted to play (the move I was most comfortable with) and then this different move, which I didn’t want to play, but it might be best. At those moments, I would silently give myself a speech, arguing that the move I wanted to play was best—and then I’d see whether I found the speech convincing.

SR: My trainer once told me that I would get into time trouble even if I began the game with five hours on my clock. There’s always lots to think about, but my time mismanagement probably derived from my neuroses—a useful neurosis. I was always motivated by the fear that I was about to make a bad move. This anxiety helped me focus, but it also slowed me down. … As for my thought process, I’ll just mention the only thing which (I think) was unusual. Often, there would be the move I wanted to play (the move I was most comfortable with) and then this different move, which I didn’t want to play, but it might be best. At those moments, I would silently give myself a speech, arguing that the move I wanted to play was best—and then I’d see whether I found the speech convincing.

EB: You’ve played several former world champions—Kasparov, Anand, and Spassky. Who was the toughest?

SR: Kasparov is the greatest player ever, in my opinion. However, I can’t say who was toughest for me, because I played these players at different strengths, under different conditions. When I played Anand, we were both 14; when I played Spassky, I was 16 and was too nervous and starstruck to think clearly; and then I played Kasparov in two clock simuls. I will say that my most awesome experience was playing blitz with Anand. He thinks several times faster than most GMs. “Touched by God” is an apt phrase.

EB: You have a day job, as a professor of philosophy. Do you still find time to play chess?

SR: I play a little on the internet, but not much. It isn’t about time. I prefer in-person play, and the nearest grandmaster is 150 miles away—my friend Ben Finegold, who runs a great club in Atlanta.

EB: Thanks for talking. Good luck with The Best I Saw in Chess.

SR: Thank you!

Follow

Follow