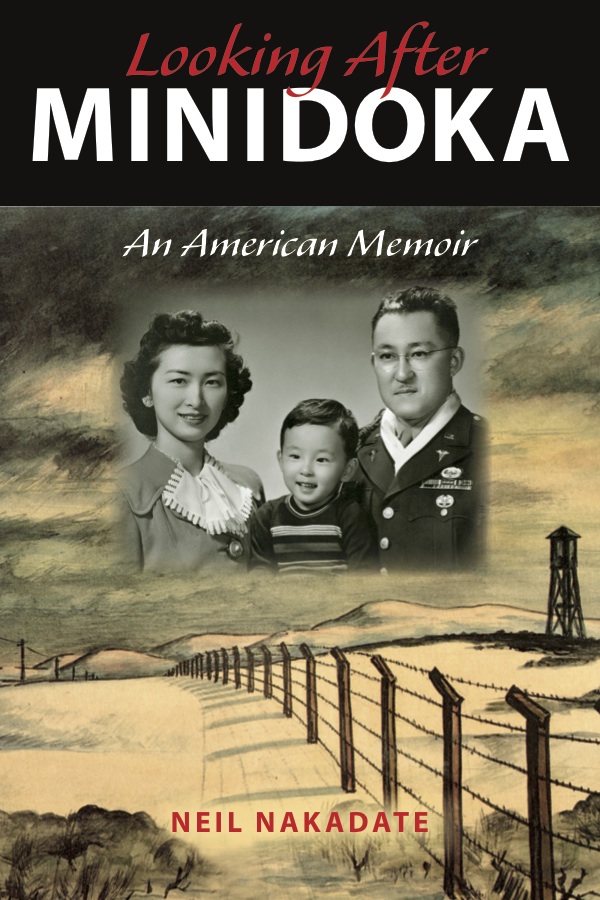

Neil Nakadate is a graduate of Stanford and earned his M.A. and Ph.D. at Indiana University. He is University Professor Emeritus from Iowa State University, where he received the Iowa State Foundation Award for Career Achievement in Teaching. He is a past president of the Board of Directors of Humanities Iowa. His writing has appeared in various publications, including Aethlon, Cottonwood, ISLE, and Annals of Internal Medicine; he has co-authored two books on rhetoric and writing and has written a critical study of novelist Jane Smiley (2010). His most recent book is Looking After Minidoka: An American Memoir (Indiana University Press, 2013), which links his Portland family and Japanese American experience from immigration through the 20th century.

Ed Battistella: Tell us a little about yourself and your career.

Neil Nakadate: I went to high school in Portland, then to Stanford. After that it was Indiana University for my M.A. and Ph.D. I taught American literature, courses on fiction, and various nonfiction writing courses, first at Texas and then at Iowa State.

EB: Your father was a doctor. I’m curious how you chose to become an English professor.

NN: My father wanted me to follow him into medicine, but in high school my affinity was for English and history—an inclination that was reinforced by some excellent teachers. In college I was pre-med until the second quarter of my sophomore year, when I gave up lab reports for writing papers on poetry and fiction. I eventually concluded that my family’s economic stability, established by two preceding generations, enabled me to make that choice.

EB: What prompted you to write Looking After Minidoka?

NN: I had been trying for years to write about my family, with a focus on the World War II years. But it became clear to me that my family embodied many of the key aspects of the larger Japanese American story—and that explaining “internment” would require discussing what preceded it and what came after. Meanwhile, I had become impatient with superficial historical accounts of the incarceration that reduced the experience to dates and statistics. I knew that the stories of individuals could provide texture and depth for the collective story. So I interviewed family members, engaged in research, read new material as it became available, and wrote and otherwise contributed in support of Redress. I organized my files. I wrote a few of the poems that would appear in the book. But I was preoccupied with teaching and writing about American literature—including multicultural American literature(s)—and rhetoric and writing. So my progress on Looking After Minidoka was fitful; more than half of it was written in the two years after I retired.

EB: What was the process of research like for a memoir spanning three generations?

NN: It was challenging but rewarding. For example, the family record included anecdotes, letters, memorabilia, interviews, ephemera, and photographs. The public record included census data and immigration records, maps, city directories, military history, and so on. I had to figure out how to sort through, organize, and present what was most valuable in all this without getting distracted and sidetracked. This was a challenge because I would periodically encounter a subtopic or detail that required me to modify my initial understanding.

EB: You were born in the Midwest and your family returned to Oregon after World War II. What are your recollections of growing up in Portland? Was the racism different than in the Midwest?

NN: When I was a boy growing up in Northwest Indiana, it was ethnically diverse and the fathers typically worked in the refineries, steel mill, or shipyard. My father had gone there because that’s where he was offered an internship upon completing medical school in Portland. The diversity of East Chicago was largely Central and Eastern European in origin. Ours was one of the few Asian families, but (according to my parents) we were accepted as part of the general mix. My memory of elementary school in Hammond is of a brief race-related incident but no ongoing problems. This was in the decade after World War II. On the post-war West Coast the “unwelcome mat” had been put out for Japanese Americans returning from the camps, and that made returning to Oregon a challenge for many, even by 1956. My parents were able to buy a house in Southwest Portland, but only after having some offers wither under the objections of potential neighbors and vacillation on the part of realtors.

NN: When I was a boy growing up in Northwest Indiana, it was ethnically diverse and the fathers typically worked in the refineries, steel mill, or shipyard. My father had gone there because that’s where he was offered an internship upon completing medical school in Portland. The diversity of East Chicago was largely Central and Eastern European in origin. Ours was one of the few Asian families, but (according to my parents) we were accepted as part of the general mix. My memory of elementary school in Hammond is of a brief race-related incident but no ongoing problems. This was in the decade after World War II. On the post-war West Coast the “unwelcome mat” had been put out for Japanese Americans returning from the camps, and that made returning to Oregon a challenge for many, even by 1956. My parents were able to buy a house in Southwest Portland, but only after having some offers wither under the objections of potential neighbors and vacillation on the part of realtors.

EB: In your book, you include a lot of your own poetry. What’s the role of poetry in a memoir like this one?

NN: The poems convey my personal connection to and feelings about elements of the larger story, and they help explain what inspired me to juxtapose my family’s story and the larger Japanese American story. Early on I knew I wanted to include the poetry, but I was also aware that publishers were resistant to mixed-genre books. Interestingly enough, by the time I finished writing, that resistance had diminished.

EB: What did you learn about yourself while writing the book?

NN: Who I am in relation to other Japanese Americans who are strangers, yet related.

EB: Today, as in the 1960’s, we are seeing a surge of civil rights protests and anti-racism. Do you see current controversies and struggles as coming out of 1960s activism or was something else at work. Or both? Are there lessons for today’s struggles against racism?

NN: What’s happening today seems in part a legacy of 1960’s protests and activism against war in Southeast Asia, for civil rights, in support of women’s rights. And both then and now what we see and say is amplified by mass media. During the 1968 Democratic Convention one salient chant heard on TV was, “The whole world is watching!” Today we have social media as part of the mix. At the core of Japanese American experience, 1960’s civil rights unrest and activism, and current issues and protests (regarding immigration, displacement and dispossession, citizenship, voting rights. . .) are some basic, ongoing questions: “Who gets to be an American?” and “Does everyone here have an opportunity to pursue the American Dream?” and “Who gets to decide, and on what grounds?”

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

NN: Thanks for asking.

Follow

Follow