Michael Erard

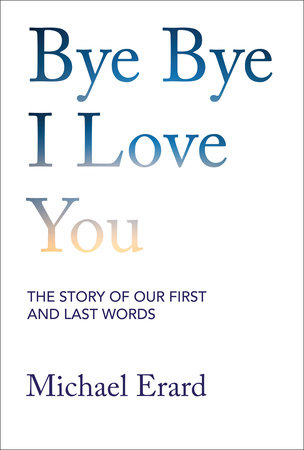

For the last five years, writer Michael Erard has been working on a book about the first words of babies and the last words of the dying. His latest book Bye Bye I Love You: The Story of Our First and Last Words, published by MIT Press (February 2025) offers a cultural history of both phenomena, bringing them together in a way that sheds new light on two important cultural rites. His work has been supported in part by the Max Planck Society, the Sloan Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Humanities, which awarded him a Public Scholars Fellowship in 2022.

Michael Erard has an MA in linguistics and a PhD in English from the University of Texas at Austin, and he has worked as a senior researcher at the FrameWorks Institute, where he helped create a method for designing and testing metaphors for use in strategic communications. In 2017, he was the first-ever writer-in-residence at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, Netherlands, and is now a researcher at the Centre for Language Studies at Radboud University in Nijmegen, Netherlands.

Erard is the author of Um…: Slips, Stumbles, and Verbal Blunders, and What They Mean (Pantheon; 2007), and Babel No More: The Search for the World’s Most Extraordinary Language Learners (Free Press; 2012. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, Aeon, The New York Times, New Scientist, Science, Down East, the European Review of Books, the North American Review, Texas Observer, and other magazines.

He lives in the Netherlands.

Ed Battistella: I really enjoyed Bye Bye I Love You, and the way that you linked the two phenomena. How did you first make the connection of studying first and last words together?

Michael Erard: The seed was holding my first child and observing him explore the world with his voice for the first time, while realizing that my linguistic powers were certainly fading. There’s also the way that his first words implied his last ones–all of the things of new life, including early communication behavior, serve as memento mori. Maybe that’s an unusual response, but for me it felt veyr natural.

I was also intensely aware that for all of my interest and attention to his early vocal explorations, I wasn’t going to witness his final ones, at least if things went conventionally the way that we hope.

EB: Are children first words always words, in the traditional sense? Are the last words always words?

ME: Their first words aren’t always adult-like forms. Sometimes they’re idiosyncratic productions that still capture an important feature of wordness: that they mean something, and that meaning is independent of a context. I would call those words. Other linguists haven’t wanted to.

And a last word, meaning a “final articulation of consciousness,” aren’t always words–they can be exclamations or interjections, as well as hand gestures, facial expressions, and even silence.

EB: Early on you say that first words are “interpersonal artifacts” (p 25). What do you mean by that?

ME: I mean they are artifacts of relationships and the slices of time in which they occur. Words don’t just happen–we produce them for each other, to each other. There is a way that the “first word” is a monumental thing, happening outside of relationship and circumstance, put on a pedestal and sent around on social media. But the first word is deeply relational. (There is always someone out there who wants to bring up talking to one’s self, or inner voices, or praying, in order to show that words do happen outside of social interaction, but I think we can agree that those are peripheral cases.)

EB: You mention your son’s first word. What was that? Did it seem important at the time?

ME: The thing we call his first word is “round-round,” which he used to describe a ceiling fan. It was immensely important at the time because it resolved itself out of his babbling. Which is to say, he was vocalizing repeatedly, then my attention shifted a bit, which is when I realized he was trying to tell me something. I repeated the word, and he responded happily to my recognition.

ME: The thing we call his first word is “round-round,” which he used to describe a ceiling fan. It was immensely important at the time because it resolved itself out of his babbling. Which is to say, he was vocalizing repeatedly, then my attention shifted a bit, which is when I realized he was trying to tell me something. I repeated the word, and he responded happily to my recognition.

So not only was there a phonological form, semantic coherence, and symbolic autonomy (three criteria of wordness set out by the linguist Lise Menn), but there was a mutual recognition by him and me that some threshold had been crossed.

However, as I wrote in the book, there were some earlier productions that should have qualified, such as this utterance “ka” that he always used to say, while pointing to something he found interesting. We puzzled for a long time about what it was. It seemed important but we couldn’t figure out how.

EB: When did American culture start getting so interested in—or anxious about–first words? It seems to be somewhat culture specific.

ME: It started in the late 19th century and the emergence of “scientific motherhood,” the idea that mothers could be enlisted to observe their babies in order to track their developmental progress. That’s when commercial baby books, many of which had spaces to write first words, became popular. It really takes off in the period where doctors, psychologists, and parenting experts are telling parents what to pay attention to.

EB: I had never heard of the Roman god Farinus, the god of first words. What did the Romans think of first words?

ME: The Romans must have thought they were pretty important, but they credited Farinus for instilling a certain style or spirit to a baby’s language, as opposed to a specific word or phrase. I was disappointed that no statue or depiction of Farinus exists, but I was excited to find out that the ancients cared enough about child language to celebrate it this way.

EB: You discuss the ways in which the reception of both first and last words in western societies has become less ritualistic and more sincere. Why has that occurred?

ME: I argue that it’s because societies have become more individualistic, and there’s no better way to mark the unique existence of a person than through their own specific first word and some singular final utterance. Here “sincere” references the truth of reality, the way things actually are. So a sincere first word is what the baby really says, not what a parent’s cultural overlay is.

EB: What would a linguistics of last words look like?

ME: It begins first of all with an ethics of care–it’s not extractive or exploitative. It also engages with the notion that dying is a social and physical process that everyone will go through, though we will bring all aspects of our racialized, enculturated, and gendered lives to the experience.

It understands the language at the end of life in terms of interaction and multimodality, and it engages with the idea that we come to our dying as embodied selves and enculturated organisms. So in the same way that child language studies tries to comb apart the self and the organism and determine which contributes to developmental outcomes, a linguistics of the end of life would help us understand what is happening both in terms of cultural expectations and the physiological and cognitive realities of dying. It would deal frontally with the challenge of what disability studies scholar Jonathan Sterne calls “normal impairment.”

It has to take into account the experiences of signers as well as talkers, and the experiences of multilinguals as well.

EB: What was the most challenging thing about writing this book?

ME: Keeping from generalisations that were too broad for the evidence that I had and worried that I had generalised anyway. From time to time I encountered a story about a death that was incredibly moving, but the immersion in the death literature wasn’t challenging in itself. As I write in the book, another seed was trying to cope with finding human remains, which sent me to the anthropology of death and dying. So I had been immersed in that for years before I began writing about language at the end of life specifically.

EB: What was the research like for this book? It seems that you’ve consulted a number of sources, archives, and little-known historical studies and a wide range of interviews. How did you find your way through the material?

ME: Once I had the basic framework about the four styles of first words, and once I had the phenomena described iin the Osler study, it became fairly easy to organize searches and go looking for materials that would fill the holes. I lucked into the archival sources and know there’s potentially much more out there to consider.

EB: What are your hopes for this book and your potential audience?

ME: I hope that the book gives people permission to re-narrate their personal stories around these linguistic milestones. I also hope it helps people to see that their cultural models around early language and language at the end of life may not contribute as positively as they think. This is especially the case with language at the end of life, where there seems to be a persistent notion that we retain our linguistic powers all the way to the last breath, which just isn’t the norm. There is also a fantasy that being present at someone’s final moment is somehow required, but in terms of bereavement outcomes, that’s not the case. So I hope the book gives people a simple idea about what language at the end of life is actually like, in the same way they have a basic idea of what babies’ language is like.

EB: I spend a bit of time overthinking your title. Did you intend “Bye Bye I Love You” as both first and last words?

ME: Me too! It’s a very challenging book to title! I actually chose one phrase as a first word and the other as a last word, but perhaps not the way you think. “Bye-bye” has been documented as a frequent first word (or one of ten first words) by English-speaking babies, and “I love you” is a frequent last word, in both anticipated and unanticipated deaths.

EB: Thanks for talking with me. Good luck with Bye Bye I Love you. It was a terrific read.

ME: Thanks!

Follow

Follow