Bill Meulemans is an emeritus professor of political science at Southern Oregon University, where he taught from 1964-1992. A former Danforth Fellow, Fulbright scholar, and Army veteran, he has a PhD from the University of Idaho and also taught at Queen’s University in Belfast, and at Portland State University.

Bill Meulemans is an emeritus professor of political science at Southern Oregon University, where he taught from 1964-1992. A former Danforth Fellow, Fulbright scholar, and Army veteran, he has a PhD from the University of Idaho and also taught at Queen’s University in Belfast, and at Portland State University.

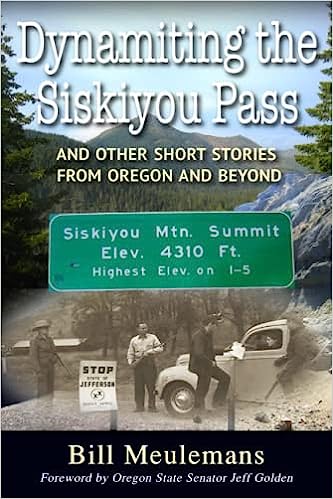

Meulemans is the author of How the Left and Right Think: The Roots of Division in American Politics, published in 2019, and Belfast: Both Sides Now published in 2013. His latest book, Dynamiting the Siskiyou Pass (Hellgate Press 2023), recounts experiences from his forty-seven-year career studying political forces that have shaped American society. His first-hand research includes interviews with Southern Oregon minutemen, members of the Rajneesh cult, and Hells Angels.

Ed Battistella: Congratulations on your memoir, Dynamiting the Siskiyou Pass, which I really enjoyed. What prompted you to write a book based on stories?

Bill Meulemans: I’ve always been aware that my students learned the most when I could present ideas in the form of a story. I firmly believe the human mind is rigged to better remember information in a story form rather than in points of isolated knowledge. I also discovered that story-telling was a great instructional tool. My students always did better in examination questions when stories were involved. An interesting anecdote gave them a context in which to remember information that might otherwise be forgotten. This book gave me an opportunity to find various “lessons” that were embedded in memorable tales. Story-telling for me is the best form of teaching. It also makes reading more enjoyable.

Ed Battistella: I was impressed with the way in which you got out into the community, interviewing people of political different views, some quite extreme. Was that sort of community involvement unusual for an academic at the time? What sorts of reactions did you get? I read that some community members wanted you fired and you even got death threats.

Bill Meulemans: I found that regular folks love to tell the stories of their lives; they want to talk about things that make them angry or proud. I enjoy listening to people and letting them develop their ideas without interruption. I always counseled my student to ask “soft-ball” questions if they really wanted to learn what makes a person tick. People who are passionate about their beliefs are more truthful when you let them talk. With this as a backdrop I invited in persons of extreme points of view into my classroom. My only rule was they couldn’t bring weapons into the room. I found that other academic people often focused on how to convert controversial speakers to a peaceful approach or proving that they were “wrong’ in their beliefs. I told my students that our job was to understand the other person, not change their minds. But my invitation to welcome extremists into the classroom was very controversial. Some local folks didn’t think my students could handle “dangerous ideas.” It seemed to me that many people missed the opportunity to understand why these guests were challenging our democratic institutions. As a people we will never be able to combat anti-democratic ideas unless we first understand why those ideas were being propagated. We need to listen to people’s stories especially when their accounts are politically disruptive in the body politic.

Ed Battistella: You mention some of your teaching experiences, inviting extremists left and right to campus. What did students learn from those visits?

Bill Meulemans: My approach in teaching was to build models that enabled students to understand the basic differences between the left and the right in political affairs, and to understand why some folks justify violence. First of all, I set out the models, then my students and I brought in moderates, activists and extremists to see if their realities fit into the models. Again, it was critical that each visitor could tell their story without interruption. When we had a friendly atmosphere, they would voice the “truth” as they perceived it. But that was also when right-wing groups thought I was endangering the minds of our youth. I found that many people spent all their energies shutting down extremists without giving any thought as to why those radical ideas were being believed.

Ed Battistella: You had some great stories. I had heard about Vortex 1, which people called Governor Tom McCall’s Pot Party, but I didn’t know about the Kent State protests at Southern Oregon College and the clever action by the college’s maintenance staff. Could you tell our reader a bit about those?

Bill Meulemans: The killing by the Ohio National Guard of four unarmed students in 1970 at Kent State University sent political shock waves to college campuses across the country. In response, students a Southern Oregon College in Ashland decided that the US Flag should fly on campus at half-mast the next day in commemoration of the those killed at Kent State. When word of this leaked out to the right-wing non-student population a determination was made by them to be ready to use any means available to raise the Flag to full-mast. Early the next morning a small fleet of pickup trucks with gunracks in the back windows showed up to raise the Flag despite the unarmed students who, by this time, were afraid for their lives. At this point it looked like another “Kent State” was in the offing. But when the Flag was attached to the rope, it was discovered that the pulley had been smashed, perhaps by a hammer. The students were relieved, the fleet of pickup trucks left, and everyone breathed a little easier. Several days later everyone on the campus found out that two unnamed college maintenance men had smashed the pully to “save us from ourselves.” These state workers became local heroes, demonstrating that maybe a bit of common sense had saved some lives that morning on a small college campus in Oregon.

Bill Meulemans: The killing by the Ohio National Guard of four unarmed students in 1970 at Kent State University sent political shock waves to college campuses across the country. In response, students a Southern Oregon College in Ashland decided that the US Flag should fly on campus at half-mast the next day in commemoration of the those killed at Kent State. When word of this leaked out to the right-wing non-student population a determination was made by them to be ready to use any means available to raise the Flag to full-mast. Early the next morning a small fleet of pickup trucks with gunracks in the back windows showed up to raise the Flag despite the unarmed students who, by this time, were afraid for their lives. At this point it looked like another “Kent State” was in the offing. But when the Flag was attached to the rope, it was discovered that the pulley had been smashed, perhaps by a hammer. The students were relieved, the fleet of pickup trucks left, and everyone breathed a little easier. Several days later everyone on the campus found out that two unnamed college maintenance men had smashed the pully to “save us from ourselves.” These state workers became local heroes, demonstrating that maybe a bit of common sense had saved some lives that morning on a small college campus in Oregon.

Ed Battistella: You’ve also written on the roots of division in politics and the different mindsets of both ordinary voters and extremists. Do you think that things have gotten more divisive over the years? I’ve often thought that the loss of the Fairness Doctrine was a crucial turning point.

Bill Meulemans: You raise the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine which I believe is one of the fundamental reasons why we are so politically polarized today. President Ronald Reagan appointed members of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that repealed the requirements for radio and television stations to provide equal time for competing ideas and candidates on the American airwaves. When Congress tried to reinstate the Fairness Doctrine, Reagan vetoed the measure. Since then, some radio and television programs have intentionally permitted lies to be told in the form of newscasts. The American people are now subject to a barrage of propaganda presented as though it was the work of “fair and balanced” journalists. In my mind the attempted insurrection of January 6, 2021`is directly linked to the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine.

Ed Battistella: You’ve also taught in Northern Ireland and done research in Israel. How would you compare the political situations there with that in the US?

Bill Meulemans: One of the stories in the book records the account of young Protestants and Catholics from Belfast I brought to Oregon on a program funded by the British government. In Oregon these young Irish students were asked about the Northern Ireland conflict is a searching question: “What’s it all about?” They couldn’t offer a meaningful answer. One of my colleagues at The Queen’s University of Belfast once told me, “The conflict was about everything and nothing.” By this he meant the dispute included everything in their lives, but it couldn’t be reduced to one topic that could be delineated and understood. I think the conflicts in Israel, Northern Ireland and the United States are all about “everything and nothing.” So much of the conflict in these three countries are in the realm of mythology, half-truths, and propaganda. Because of this, the average person is often deluged by a maze of disturbing ideas that cause them, in anger, to turn on each other. In my judgment, it would be wise, in all three nations, that a Fairness Doctrine be observed by the media. It is absolutely necessary for both sides to be heard honestly if our democracies are to survive.

Ed Battistella: You were involved in researching groups as diverse as the Hell’s Angels, the Rajneeshees, the Ku Klux Klan and more. How did you manage to gain access to these groups?

Bill Meulemans: My approach was to ask simple questions in such a way that individuals could analyze themselves. For example, when I was with the Hell’s Angels, I asked their leader, Sonny Barger, how he visualized himself in the stretch of history. At this point his eyes sort of glazed over and he said if he had been born in the middle of the nineteenth century, he would have been an outlaw that led a gang on horseback that robbed stagecoaches. I found that the rank-in-file Rajneeshees loved to see themselves as being the first to create a “perfect society” where “complete freedom” could prevail. And Ku Klux Klan members I interviewed saw themselves as an embattled minority that were sorely misunderstood by the American people. I found these folks loved to tell their stories, and we owe them the respect to listen, especially when they are threatening to undermine American democracy.

Ed Battistella: You taught at SOU—then-Southern Oregon College—for almost 30 years and served as chair of the faculty Senate. Any favorite campus recollections you’d like to share?

Bill Meulemans: First of all, I am a firm believer in faculty governance. Members of the university community should bear responsibility for the quality of education and the manner for handling academic disputes. But I am also aware that college faculty members are not noted for making clear decisions. After being on the faculty senate for several years, I became aware that our agenda was often like a carousel, in that the same issues came up again and again, year-after-year. We discussed all the finer points of academic policies without finding any solutions. Our disagreements were often lively and memorable, but we seldom changed important procedures. This topic reminds of a comment made by a colleague at The Queen’s University of Belfast. He said, “the debate among college professors is so vicious because the stakes are so low.” I say this as one who was deeply involved in the process.

Ed Battistella: As an expert observer, do you have any predictions for the current election cycle?

Bill Meulemans: I go back to the comments about the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine. So far that action is, in part, responsible for the near destruction of one of our two great political parties and the deterioration of our former widespread believe in democratic values. In my judgment, the upcoming primary and general elections may decide whether American political institutions will stand or be put aside in favor of an emerging authoritarian system that is evolving in the current campaign. This may be the most important election season of our entire political history.

Ed Battistella: Thanks for talking with us.

Bill Meulemans: Thank you for the opportunity to talk with you.

Follow

Follow