Jon Raymond is the author of the novels The Half-Life, Rain Dragon, and Freebird, and the story collection Livability, winner of the Oregon Book Award. He was the editor of Plazm Magazine, associate and contributing editor at Tin House magazine, and a member of the Board of Directors at Literary Arts. He lives in Portland.

Jon Raymond is the author of the novels The Half-Life, Rain Dragon, and Freebird, and the story collection Livability, winner of the Oregon Book Award. He was the editor of Plazm Magazine, associate and contributing editor at Tin House magazine, and a member of the Board of Directors at Literary Arts. He lives in Portland.

His writing has appeared in Zoetrope, Playboy, Tin House, The Village Voice, Artforum, Bookforum, and other places.

Raymond is also a screenwriter and has collaborated on six films with the director Kelly Reichardt, including Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, Meek’s Cutoff, Night Moves, First Cow, and the forthcoming Showing Up, numerous of which have been based on his fiction. He received an Emmy Award nomination for his screenwriting on the HBO miniseries Mildred Pierce.

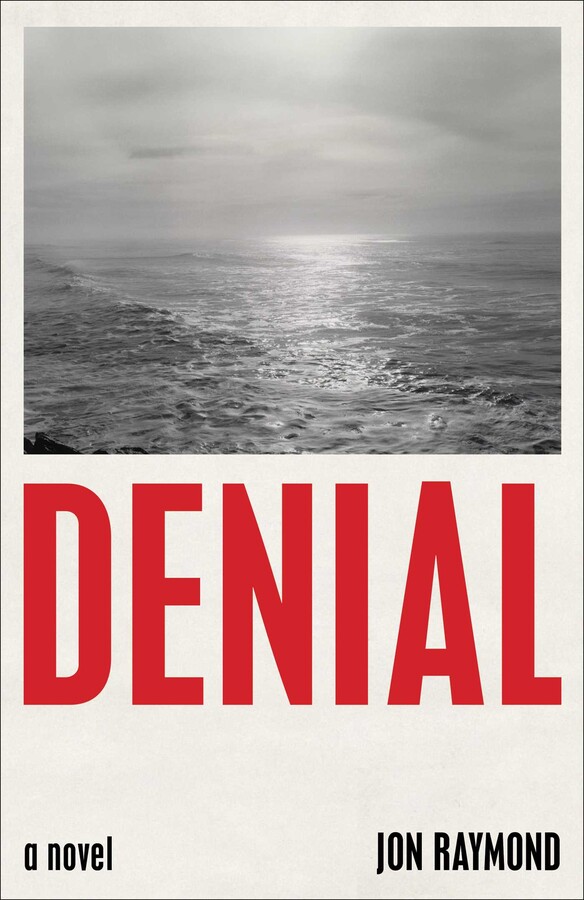

Jon Raymond’s most recent book is Denial (Simon and Schuster, 2022), futuristic which Kirkus Reviews called Denial “A cool, compelling take on an incendiary topic,” and Newsweek said it was “subtle and morally engaging.”

Ed Battistella: I really enjoyed Denial, which is set in 2052 after a series of climate disaster leave to world-wide protests known as the Upheaval, after which environmental criminals were tried, Nuremberg-like. How did you come up with the idea for the novel?

Jon Raymond: I’d say the book stemmed from an argument I’ve been having for a long time in my brain with post-apocalyptic and dystopian literature and film in general. Pretty much my whole life I’ve been reading and watching stories about the destruction of the planet. I’ve seen the world destroyed by meteor, zombie, pandemic, patriarchy, nuclear bomb, etc., etc., ad nauseum. At some point, to me, the fantasy has started to seem like a death wish. Humanity obsessively fantasizing its own annihilation, almost willing the worst possible fate to unfold. I decided I wanted to write a book that got off those rails and foretold a future wherein human and plant-life continues to survive, and in some ways, even, to thrive. That’s a much harder act of imagination, I think, but one that’s really necessary right now. It’s beyond time we started putting our minds to what a plausible, livable future might look like, given our situation.

More specifically, I’d heard of this idea for Nuremberg-style trials for climate criminals, and with that in mind, I could see a kind of Nazi-hunter story in eco-garb. I thought that idea had potential.

EB: Your protagonist, journalist Jack Henry makes contact with the fugitive pipeline executive Bob Cave when it turns out they are both reading Mark Twain novels in a coffee shop. What prompted you to use Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer?

JR: In this future world I was imagining, I wanted the characters to be reading novels. That was part of the optimism I was projecting, people still reading. And I decided early on that I wanted the novel they read to be Huckleberry Finn. I felt like that book’s themes of friendship and disguise kind of feathered with my own themes, as I saw them, and the never-ending racial controversies pointed at a sadly permanent fixture of the American experience, even decades beyond our current times.

I was also thinking about Huckleberry Finn because of the sculpture by the artist Charles Ray. It’s a stainless steel double portrait of Huck and Jim as nine foot tall nudes, an incredibly simple but potent piece of art, I think. Just this pubescent white boy, Huck, and this middle-aged Black man, Jim, standing beside each other, naked. Back in 2014, the Whitney had to de-install it due to the controversy it sparked. I guess something about a naked Black man and white boy in close proximity is still real hot potatoes.

Anyway, I’ve thought about the book differently ever since seeing images of the sculpture. How often does that happen, a sculpture changing how you read? I wanted my characters to be reading Huckleberry Finn in the spirit of Charles Ray. I wanted my two characters to talk about Huck and Jim and grapple with the longevity of Twain’s text in the American imagination.

EB: A lot of the suspense is psychological and that seems to be reflected in the title. It seems that all of the main characters were in some sort of denial.

JR: For sure. There’s barely a scene that isn’t structured by some unstated duplicity or self-delusion. Jack the reporter lives in denial; Bob the climate criminal lives in denial; humanity lives in denial. I was interested in the idea of denial as as an epistemology of sorts, a way of knowing. Denial as a prerequisite for consciousness, even. I deny, therefore I am.

EB: There was a point near the end when I felt a bit sorry for Bob Cave, one of the Empty Chairs tried in absentia. How did you build his character?

JR: I wanted him to be pretty likable. Otherwise, who cares if he gets caught and unmasked or not? So I made him a fairly sophisticated, possibly even somewhat repentant representative of the petrol-empire. In particular, I made him a Sunday painter in the style of LBJ or George W. Bush, two war criminals who found their artistic muses after their retirements from death-dealing. It’s a good tactic, it turns out. People forget what you did while you were in power while they’re looking at your paintings.

JR: I wanted him to be pretty likable. Otherwise, who cares if he gets caught and unmasked or not? So I made him a fairly sophisticated, possibly even somewhat repentant representative of the petrol-empire. In particular, I made him a Sunday painter in the style of LBJ or George W. Bush, two war criminals who found their artistic muses after their retirements from death-dealing. It’s a good tactic, it turns out. People forget what you did while you were in power while they’re looking at your paintings.

EB: It seemed to me that there was a great deal of interesting research involved in the book, eclipses, prions, bullfighting, journalism, the art of Guadalajara, Mexican culture and Aztec mythology. As a writer how do you research and weave those details in. The details felt very intentional.

JR: I tend to do research that’s only explicitly necessary to the story and character at hand. I don’t spend a lot of time doing “deep dives” or chasing any kind of mastery of anything. I figure out what I need for a given character or scene, and find out what I need to know to maintain the illusion of competence. That’s my method! Of course, it never goes like that. I end up having to figure out a bunch of extraneous stuff along the way. But I really try to let the story guide me.

And then sometimes there’s something I want to get in there one way or another. I knew I wanted the characters to visit the murals by Orozco in this book, for instance. I knew them and loved them and wanted to force my characters to deal with them together. So in that case, I had some knowledge and I shoehorned it into the pages.

EB: I was stuck by how normal the future seemed after the upheavals. Your telling reflected catastrophic change but also adaptation. It wasn’t a full-on sci-fi dystopia. Do you think we’ve had enough of dystopia?

JR: Personally, I’m super bored of dystopia. As I said above, I think it’s usually at best cliched, at worst a kind of death trip. Not to say the future looks very great, but I think we have a better chance of survival if we start thinking in more measured, non-hyperbolic ways.

EB: What was the toughest part about writing the book?

JR: This book actually came really easily. I wrote it during lockdown, so the writing conditions were very conducive. No distractions, no obligations. And I felt like the traumas of the world were resonating with the story I was trying to tell, which gave me a sense of urgency in the writing. Also, it was always going to be short, so I could see it was going to work pretty quickly. I’m pretty sure the book I’m working on now will not be so simple. Sometimes they go easy and sometimes they’re hard. I wish I knew how to predict which was which but so far I can’t.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

JR: Thank you!

Follow

Follow