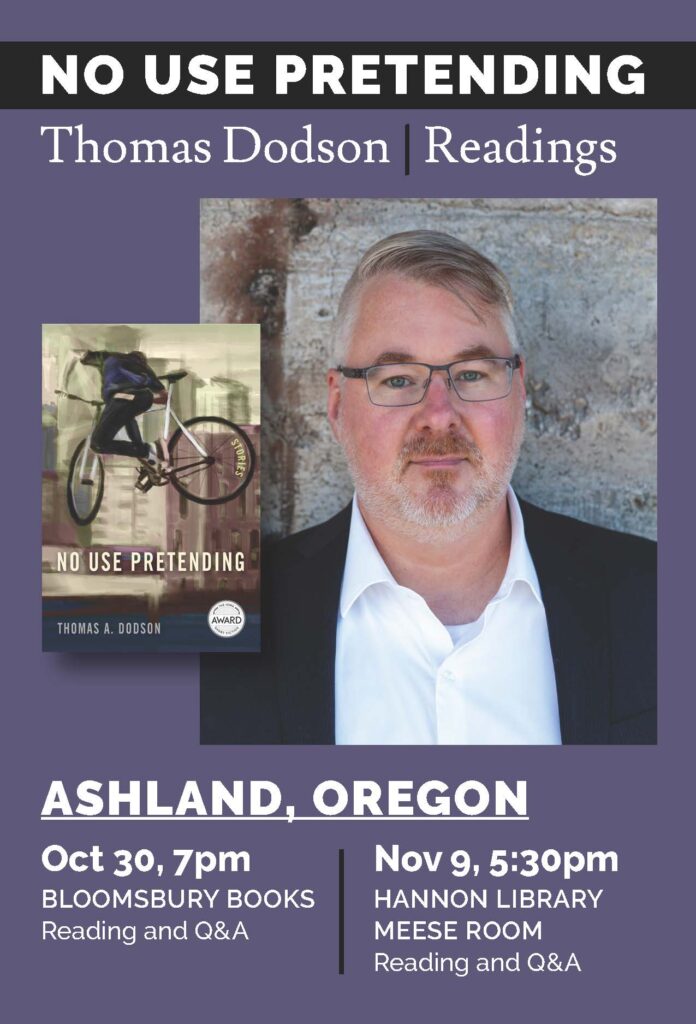

Thomas Dodson is an assistant professor and librarian at Southern Oregon University. His story collection, No Use Pretending, was selected by Gish Jen for the Iowa Short Fiction Prize and is forthcoming from University of Iowa Press.

Thomas Dodson is an assistant professor and librarian at Southern Oregon University. His story collection, No Use Pretending, was selected by Gish Jen for the Iowa Short Fiction Prize and is forthcoming from University of Iowa Press.

He holds graduate degrees from the Ohio State University, Kent State University, and the University of Iowa, where he was an Iowa Arts Fellow at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in fiction.

His fiction has appeared in The Missouri Review, Gulf Coast, The Cincinnati Review, and elsewhere. His short stories have been awarded the 2022 Robert and Adele Shiff Award and the 2020 Jeffrey E. Smith Editors’ Prize. His story “Keeping” was selected by the editors of Best American Short Stories as a distinguished story of 2022. He has been the runner-up for the Autumn House Fiction Contest and a finalist for the WICW Fiction Fellowship, the Glimmer Train Award for New Writers, and the Hamlin Garland Award for the Short Story.

Thomas Dodson grew up in northeast Missouri and has graduate degrees in comparative cultural studies and in library science. He lives in Ashland.

No Use Pretending was praised for its “range of emotions and voices (Jess Walter, author of The Angel of Rome and Other Stories), the “complicated humanity” of its characters (Margot Livesey, author of The Flight of Gemma Hardy), and its “captivating vision of hope, regret, and resilience” (Tom Drury, author of Pacific).

Thomas Dodson will be reading from No Use Pretending at Bloomsbury Books, on October 30, at 7 pm and in the Meese Room of the Hannon Library on November 9, at 5:30 pm.

Ed Battistella: Congratulations on No Use Pretending.

Thomas Dodson: Thanks, and thanks so much for your interest in the book!

EB: This is a wide-ranging, ideas-based collection, covering everything from beekeeping, drone warfare, fracking, Buddhism, and Greek mythology. These aren’t everyday fiction topics. Can you talk a bit about the research you do—and where your expertise as a librarian fits in?

TD: I think a lot of writers begin with a character that interests them and build out from there. I do that sometimes, but just as often for me it’s an idea or a curiosity about something that’s happening in the world.

Like with the story about the drone pilot stationed just outside Las Vegas. I was interested in these two forms of American power, both of which have to do with vision—the power to see and act at a great distance with drones, and then, with Las Vegas, the bright lights, casinos, and strip clubs, the power to sort of overwhelm the senses with capitalist spectacle and sex-as-commodity.

I could try to write an essay about all this, but honestly, I’m much more interested in exploring those issues and ideas through the lived experience of a character. That experience is fascinating to me. And getting at it—what it’s like to be a drone pilot, to be fighting a war on another continent and then clocking out and helping your kids with their homework—that requires a good amount of research that goes beyond abstractions about the ethics of drone warfare or understanding the policy positions. I needed to know, for example, what slang the pilots used among themselves, what the trailers they worked in smelled like (not good), what it was like to be married to someone living that life. The work of getting that kind of information is made a lot easier because of my training as a librarian.

Also, I agree with what John Gardner says in The Art of Fiction, that a conventional story should evoke a “vivid and continuous dream” in the mind of the reader. That dream is a delicate thing and lots of things can jolt the reader out of it—bad prose or flat characters, for example. So, it really wouldn’t make sense to load down a story with a bunch of footnotes like an academic work. Still, I want to credit the work of the journalists, philosophers, and others that made it possible for me to write each story. To that end, and to give the reader interested in a topic explored in one of the stories a place to go for more, I have a page on my website dedicated to the sources I’ve drawn from: https://thomasadodson.com/sources.

EB: What goes through your mind as you are developing a character? I found myself noticing a lot of small details that shaped my understanding of the characters, like the way that you mention the cat as Kenzie’s “familiar” in “Fault Trace” or the description of Sandy’s perm as being “like a halo of dishwater foam” in “Creek People.”

TD: In developing and presenting characters, I think I’m always striving for details that are particular and feel authentic. I also try not to shy away from characters who are “difficult.” I want characters to feel real, and real people are flawed in the most interesting ways. That’s occasionally gotten me into a little trouble with readers who want characters to be “likeable” or “relatable,” which isn’t at all what I’m going for. I really like what Steve Almond has said about difficult or unappealing characters; he says he’s opposed to “a mind-set that position[s] fiction as a place we go to have our virtues affirmed rather than having the confused and wounded parts of ourselves exposed.”

I’ve always been a reader who is most drawn in by stories that render the complexity, confusion—and yes, even the darkness—in human beings and their relationships to one another. Likeable or not, I hope my characters have that complexity, that they may be messed up in some ways, behave badly in some situations, but that doesn’t exhaust who they are. The reader may not always like them, but I hope as a story progresses, the reader comes to understand them and empathize with their struggles.

EB: I’m curious about the title of the collection. For me, it seemed that many—or at least several–of the stories were about characters pretending this are one way not another—trying to skip out on reality.

TD: Yes, exactly. The title has several meanings for me. Denis Johnson, probably my favorite writer, has said: “There’s nobody who can disguise himself. Eventually we’re all outed in one way or another.” In one sense, I think the stories are about that. How we try to disguise ourselves, present an idealized or false version of ourselves, to others, but also to ourselves because facing up to our flaws is difficult and humbling. We’d rather not go there. I try in these stories to put characters in situations where they have to confront who they really are beyond those superficialities and disguises.

TD: Yes, exactly. The title has several meanings for me. Denis Johnson, probably my favorite writer, has said: “There’s nobody who can disguise himself. Eventually we’re all outed in one way or another.” In one sense, I think the stories are about that. How we try to disguise ourselves, present an idealized or false version of ourselves, to others, but also to ourselves because facing up to our flaws is difficult and humbling. We’d rather not go there. I try in these stories to put characters in situations where they have to confront who they really are beyond those superficialities and disguises.

I also want to push back a little against the idea that art should serve some social purpose beyond itself, that it needs to be subordinated to the ends of politics or edification or whatever to be truly worthwhile. I would say that art shouldn’t have to have utility in that sense; it shouldn’t be expected to “do” something to improve society or the reader. But, of course, this is a point on which reasonable people can disagree. I just intend with the title to playfully position myself on one side of that argument.

And speaking of playfulness, a more straight-forward sense of the title is simply that this kind of storytelling is a kind of adult “pretending.” I get to pretend to be someone else writing the story and the reader gets to pretend to be someone else reading it. I try to deal with serious things in the story, but I don’t want to completely abandon that sense of being a kid and playing and making up stories.

EB: I’m curious too about the arrangement of the eleven a stories in No Use Pretending. Was it difficult to put them put them in order or did it come easily?

TD: Well, I feel like with a story collection you want to try to both start and go out with a bit of a bang. So, I’ve positioned what I think are my strongest stories first and last; they also happen to be my most recent ones, written while I wrapped up my time at Iowa. Beyond that, I think the middle section all has to do with mythology in some way—a Greek myth, a sort of Kafkaesque fairytale, and a little flash piece about the mythmaking we engage in as we try to understand our relationships with our parents. Also, addiction is a definitely a theme in the book and even though there isn’t a clear arc across the stories—like a redemption narrative or something—I did want to end with “The Watchman,” which is a story about recovery and making meaning out of life after addiction rather than just the pain of being stuck in the midst of it.

EB: Can you say something about your process as a writer. The stories in No Use Pretending seem finely polished.

TD: Thanks; I’m glad you think so. I used to have some pretty dumb ideas about genre—what was “literary” and what wasn’t, but I like to think I’m past that now. I do think the kind of fiction I enjoy reading and want to write is very concerned with the style of the prose, shows that the writer has taken great care with that, is trying to engage the reader with the language at the paragraph and sentence level.

Not all fiction aspires to do that, or needs to do that; in some genres, the readers might even find it annoying: “yes, yes, get on with the plot, would you?” I used to fit these differences into a hierarchy of “quality,” or “literary” fiction versus “commercial fiction.” I can still fall into that sometimes, but now I mostly just see this as a matter of genre conventions and personal taste—even “taste” is a loaded word; let’s say “preference.” I have my preferences and I guess I just hope to reach readers who also appreciate a good line for its own sake beyond how it functions to further plot or character or some other element.

As for process, I worked on these stories over many years, workshopping to get feedback from other writers, revising each several times, and publishing them as I went along. As for my process, it’s a mess really; I have long fallow periods, or periods when I’m mostly jotting down ideas and doing research. I’ve been researching a novel over the summer, for example, but I hope to be back to the writing desk again this fall. Writing fiction has always been a bit fraught for me. I write confidently and without much stress or doubt all the time. But fiction is different. Each time I sit down to work on a story draft, I wonder all over again if I’m still going to be able to do it. Luckily, so far at least, it’s worked out.

EB: Your website warns readers “Don’t even get him started about typography, continental philosophy, or climate fiction.” Dare I ask?

TD: Not unless you want to fire up a whole other interview. That said, I’m happy to talk to pretty much anyone anytime about those topics.

EB: What’s your backstory as a writer? Who are some of the writers who have influenced you?

TD: Really a lot. I learned a great deal from reading Mary Gaitskill, Denis Johnson, Lorrie Moore, Toni Morrison. I could go on and on.

EB: What are you currently working on writer-wise?

TD: I’m working on a novel draft called “The Tower of Abraham,” about an imagined community that forms in a vacant and half-constructed office tower in Boston’s financial district. It’s based on an actual community that occupied an office tower in Venezuela, Torre David.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

TD: Thanks so much for having me!

Follow

Follow