Christina Ward is an independent cultural historian of food and food history, exploring what we eat and why we eat it. She is the author of American Advertising Cookbooks-How Corporations Taught Us To Love, Spam, Bananas, and Jell-O, and Preservation-The Art and Science of Canning, Fermentation, and Dehydration.

Christina Ward is an independent cultural historian of food and food history, exploring what we eat and why we eat it. She is the author of American Advertising Cookbooks-How Corporations Taught Us To Love, Spam, Bananas, and Jell-O, and Preservation-The Art and Science of Canning, Fermentation, and Dehydration.

She is a contributor to Serious Eats, Edible Milwaukee, The Wall Street Journal, Food & Wine magazine and more. She also rode around town in the Oscar Meyer Wienermobile with Padma Lakshmi on the hottest day in July of 2019 for “Taste the Nation.”

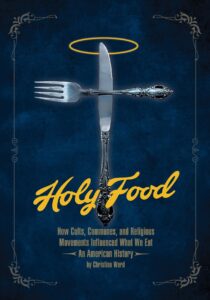

Her current book is Holy Food: How Cults, Communes, and Religious Movements Influenced What We Eat—An American History (September 26, 2023).

Ed Battistella: I’ve taught courses on the language of food and on the rhetoric of cults, so Holy Food was a really interesting book to me. How did you think to combine the history of spiritual movements with the history of food?

Christina Ward: Food and religion are the twinned obsessions of my life. I remember as a young child being fascinated when I heard people saying they could or could not eat something because of their religion. I grew up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin—a very Catholic city—and there were kids in the neighborhood “giving up” foods for Lent. The notion that someone’s god (or gods) would care about what a person eats set me down this path. It took five years of active research and writing to get Holy Food to “book”, but I’ve been thinking about how food and religion are intertwined for decades.

EB: What does the history of food tell us about culture?

CW: Based on my research, I think humans tend to “sacralize” foods we enjoy and elevate their significance in ways that help us identify our community of like-minded people. The food itself is often inconsequential—the recipes from these groups show that many are following trends and fads—it’s the notion that specific foods have importance assigned to them that makes an item part the culture. The foods themselves are benign, it’s the meaning we give it. While not entirely a closed loop, our food reflects our culture, and our culture reflects our food. There is a built-in tension between what and how to eat and how we interact with our culture. That includes religious culture. In the US, we often view food through a judgmental lens–teasing among friends and family when someone in the group adopts a different eating pattern to the extreme of “dosing” vegetarians and vegans with meat. In mainstream America, rejecting a type of popular food is often viewed as a judgement against American culture.

EB: What was it about the Great Awakening of the nineteenth century that brought about so many food fads, I guess you could call them?

CW: The advances in tech sped everything along. A mechanized printing process allowed for an exponential increase in newspapers, books, and tracts. New religious ideas, coupled with food prohibitions and ideas for a new type of diet flooded the country. The Book of Mormon was printed in 1830 and has remained in print to this day. By early 1844, apocalyptic preacher William Miller’s tract about his divinely revealed system for calculating the end of the world had reached 500,000 people.

Access to cheap printing also allowed many groups to publish cookbooks which had the double-pronged goal of teaching new converts about a group’s diet and act as an attractant for potential new believers who were interested in the food. For groups like the Seventh Day Adventists, which was formed out of the chaos among Millerites when the world did not end in 1844, their vegetarian cookbook became a lodestone for numerous groups embracing vegetarianism.

EB: You discussed the Nation of Islam diet in Elijah Muhammed’s How to Eat Live. How did that come about?

CW: Rarely discussed is how much of a role personal taste of a group’s leader plays in their cuisine, but it happens. For the Nation of Islam, food became a core concern under the leadership of Elijah Muhammed. His philosophy was partially informed by the “Tuskegee Idea” that Blacks should form separate and self-sufficient communities and never rely on white people for anything. Muhammed felt the processed foods made by white-owned corporations and sold to the Black community were a method of poisoning and controlling Black bodies. He advocated for a spartan diet of one meal a day of mostly grains and vegetables with fish and chicken proteins as acceptable in small amounts. He imbued NoI food culture with political meaning as well by forbidding foods associated with southern enslavement of Black people. Specific beans were allowed while others prohibited. He felt that overuse of salt was making people sluggish. While not every member of the NoI followed every dictate in How to Eat to Live, enough people followed most of them. Adhering to Muhammad’s diet results in a healthy body to this day. The NoI breakdown of 50% vegetables, 30% bean proteins and grains, and about 20% meat proteins is nearly the same macro breakdown of what is recommended by USDA nutritionists.

EB: One of the fascinating things for me was hearing about how many of our common foods got their start as specialties of religious communities, things like strawberry shortcake and veggie burgers, which then made their way into the mainstream and becoming commodified. Are we still seeing that with today’s cult foods?

CW: Absolutely yes! Tofurkey was developed at The Farm Community in the 1970s and is sold throughout the US in mainstream chain grocery stores. The Kettle brand of potato chips is owned by the 3HO group founded by Yogi Bhajan. Celestial Seasonings Tea’s founder was a devoted adherent of the Urantia Book. I’m sure that there is a small group somewhere in the United States that will come up with the next big food brand in the coming decade.

EB: Holy Food has 75 historical recipes for things like Rejuvelac, Moor Salad and Dilly Bread, and you’ve updated and tested all of these. Do you have a favorite? And a least favorite?

CW: I have a sweet tooth and am partial to desserts! Shaker Apple Pie is good and surprising because it uses rosewater as its main flavoring agent instead of the now familiar cinnamon. The Apple-Corn Cookies are great. They’re gluten-free but delicious even if you’re a wheat eater. On the savory side, the House of David’s Walnut Loaf is quite good as are Tassajara’s Nut-Buttered Beans.

CW: I have a sweet tooth and am partial to desserts! Shaker Apple Pie is good and surprising because it uses rosewater as its main flavoring agent instead of the now familiar cinnamon. The Apple-Corn Cookies are great. They’re gluten-free but delicious even if you’re a wheat eater. On the savory side, the House of David’s Walnut Loaf is quite good as are Tassajara’s Nut-Buttered Beans.

The misses for me are entirely about personal taste as well as food allergies. I can’t eat fish or any meat and relied on chef friends to test and refine those recipes. I know they did a good job but that will be up to folks who try those recipes out. Of the recipes I tested, the ones that were really disgusting I left out of the book. One of my goals was to include foods that modern eaters could make and potentially enjoy. Eating what these groups did helps give more insights into their lives and beliefs. The worst item tested was from the True Light Beavers who had a recipe for Mock Chopped Liver Pate made from mushrooms and other ingredients. My initial thought from analyzing the ingredients was that it would taste pretty good; it did not. One of the few foods that honestly made me gag.

EB: Holy Food is a very visual book. You’ve got photos of spiritual leaders, communes, and cookbooks and on just about every other page. How did you manage to track down all those great images?

CW: Holy Food is not an academic book (though I researched and wrote it with academic rigor) and is for general readers. I feel that images provide another form of information for readers to fully understand what people believe.

I think it’s also too easy to take the cheap shot and mock people who followed religious gurus or charlatans. As a researcher and cookbook collector, I’ve felt that there is too much great visual language lost when we don’t see contextual images. Seeing pictures of people laughing at Jonestown adds nuance to the story we think we know. Seeing George Washington Carver as a vigorous young man standing in a field of his hybrid plants communicates so much about him. Moreso when most images of Carver online and in books depict him as an old man.

I spent time (maybe too much time) in museums and libraries seeking out images. Oftentimes finding one image would lead to others. Pictures of Nation of Islam founder Wallace Farad (sometimes Fard) are notoriously rare. On an unrelated trip to Detroit, I visited the main library who holds the Detroit Free Press photo archives and within minutes—and with the invaluable assistance of the librarians—I found an image of Farad. Even the librarians were thrilled. And of course, in the case of many of the 20th century groups, they have images of their members and founders. Most groups were happy to share images. That they were willing to share was based on my approach to the material, I tried to refrain from judging any group or their beliefs unless those beliefs were coercive and destructive.

EB: If you had your own cult, what would the cuisine be like?

CW: I mentioned that I’m a vegetarian with a sweet tooth, so my cuisine would be most similar to the Hare Krishna diet but with more cakes, pies, and cookies. I would also sacralize chocolate into a ritual that gives me the authority to eat a few candy bars per day. Not a very healthy diet but when one declares themselves godhead, anything goes.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

CW: Thank you for your interest! My hope above all else is that readers marvel at how relatively small groups and individuals have an outsized influence on our modern food.

Follow

Follow