Daniel Alrick is a graduate of the Professional Writing English program at Southern Oregon University and Chair of the Oregon Council on Developmental Disabilities.

EB: Tell our readers a little bit about Stephen Weiner and his work.

Stephen Weiner

DA: Stephen Weiner was the publisher of the local newsletter The Suspicious Humanist, a newsletter of literature and political writing. He was a Stanford graduate and journalist who wrote extensively on mental health in personal essays that were published in Classics of Community Psychiatry and The Oxford Handbook of Psychiatric Ethics. Throughout his life, Steve was active in left-wing politics , counterculture, and Jewish identity. He also wrote about the experience of living with schizophrenia and being an “adult in need of the welfare state” to quote one of his articles, and social programs for the disabled.

And Steve was a community librarian, who kept a library of hundreds of books in his small apartment, often keeping multiple copies that he would loan out to others.

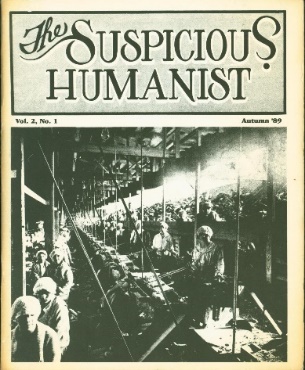

EB: What was The Suspicious Humanist and how did it come about?

Milton Weiner

DA: The “suspicious humanist” was his father, Milton Weiner, who was the original publisher, editor, and author of the newsletter in 1970 out of San Francisco and Sausalito, California. Steve inherited the newsletter and title from him.

Milton was a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, which he had fought in as an American volunteer on the Republican side. He believed in fighting fascism in Spain because he had experienced anti-Semitism from the Ku Klux Klan while growing up in New Jersey during the 1920s. But while in Spain he discovered the war against Franco nationalism was sidetracked by the warring factions of the Communist party. When he returned to America, he enlisted in the Army and fought in WW II as a soldier in the Dixie Division.

Milt was wounded in both wars and was later an advocate for disabled veterans. After Milt’s service in WW II he was a soil scientist before he was blacklist and labeled a “premature anti-fascist” for his time in Spain and his membership in the communist party.

All these political disillusionments and betrayals led him to conceptualize the notion of being a “suspicious humanist,” a sort of ancient mariner of the old left who was skeptical of the new radicalism emerging from California in the 1960s–a political movement his son Steve would become a part of in his youth. In Milt’s view, he had fought in the battle of peace and fascism for real, while the New Left was just talking about revolution in a pretentious way. He believed that he had dealt with matters of existential importance and survival, so his children did not have to. Milt’s world-weary philosophy of humanism summed up was “Just like you, I was born without pockets and a fair share of my urge to help my fellow man.”

Steve embraced those values, but he was torn as a child of the sixties between his idealism toward leftist politics and his own challenge with understanding mental illness. Steve also experienced his own personal sense of betrayals in radical politics. On top of that how does he measure up to the looming presence of his massive father figure in Milt, a bona fide war hero. Being a suspicious humanist, as both father and son would come to believe, is marching to your own drum in politics and humor, a sort of ronin for having both survived and fought in the arena of life.

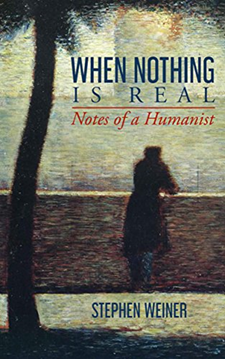

EB: How did you get involved in the publication of Stephen Weiner’s book When Nothing is Real: Notes of a Humanist?

DA: Steve had worked on his memoir for many years as a handwritten manuscript on notebook paper, which was then edited by local author Richard Seidman. I got involved with Steve primarily from our friendship and interest in politics and books. Through our conversations I gradually became interested in the story of his father, Milt. And through compiling research into Milt’s biography I became more involved in the stewardship of Steve’s papers from The Suspicious Humanist. As Steve became ill with stage four kidney cancer it became a race against time to complete his own memoir and secure the surviving records of Milt. What became apparent to me was that Steve was living out a lot of his own life in the shadow of Milt, whether or not his father loved him, and how he had measured up to the old man in terms of his political journey. It was in a way a release of two ghosts upon the end of that life cycle.

EB: How would you characterize his work: political theory, psychology, philosophy, advocacy, memoir?

DA: The book contains all of those elements. But it is primarily a philosophical memoir. What Steve undertook was a life of letters, reading and writing, to understand both his personal, mental condition and his times as a Baby Boomer and Jewish man in left-wing politics. Readers will find much to relate to in terms of Steve’s chronicle of the political upheaval in California of the 1960s, but also frank admission of loneliness and weariness at the hand he had been dealt. In comparing the lives of Milt and Steve, I was struck by how much more existential Milt is about matters of his security and survival, while Steve is drawn much more intimately into the anguish of family trauma, his parents’ divorce, the death of his sister, spiritual fulfillment, and his thoughts on sexuality, health, and mortality. Milt had a less enlightened view on mental and emotional illness. Steve was more the humanist, while Milt was the suspicious ronin.

DA: The book contains all of those elements. But it is primarily a philosophical memoir. What Steve undertook was a life of letters, reading and writing, to understand both his personal, mental condition and his times as a Baby Boomer and Jewish man in left-wing politics. Readers will find much to relate to in terms of Steve’s chronicle of the political upheaval in California of the 1960s, but also frank admission of loneliness and weariness at the hand he had been dealt. In comparing the lives of Milt and Steve, I was struck by how much more existential Milt is about matters of his security and survival, while Steve is drawn much more intimately into the anguish of family trauma, his parents’ divorce, the death of his sister, spiritual fulfillment, and his thoughts on sexuality, health, and mortality. Milt had a less enlightened view on mental and emotional illness. Steve was more the humanist, while Milt was the suspicious ronin.

EB: What’s the significance of the book’s title?

DA: We talked about the title in the days leading up to his death. “Nothing is Real” referring primarily to Steve’s struggles with paranoid schizophrenia, in reference to the Beatles song “Strawberry Fields Forever.” Which goes to show how Steve was very much a product of the 1960s. Steve believed in enlightenment values and secular humanism but rejected postmodern ideas.”. He resisted and resented the notion that life was an illusion or that objective reality was an ephemeral space, but he also wanted peace of mind in the basic common decency of kindness and thoughtfulness. He had joked to me that he wanted the quote “I tell you, we are here on Earth to fart around, and don’t let anybody tell you different” to be his epitaph, but decided on a quote from Henry Miller instead.

EB: What was the process of putting the book together like?

DA: It was a struggle of the sundown in Steve’s life. He was very ill with diabetes and COPD and then was dying quickly of stage 4 cancer. His memory remained sharp, even in his weariest moments, up until the final weeks in which those synapses started to fail. Richard Seidman did the work with Steve editing the manuscript and designing it for final publication in approximately the last two months of Steve’s life, while I was doing much of the final interviews with Steve and trying to trigger any bits of useful info. I was also collating all of Steve’s surviving papers, along with old records from Milt he had forgotten about. I wrote a draft of the afterword for the book while visiting Steve in the hospital and was watching a video tape of Milt when I received a phone call that Steve had died later that day.

EB: What’s been the reaction so far?

DA: Steve’s friends and family were very supportive, and the people who knew him in Ashland fondly remember his political advocacy and involvement in the Jewish community. Like Milt, Steve was strongly opposed to what he felt was anti-Semitic language on the political left. And what has become clear is how much resonance there was among people who knew Steve from his diligence to remain active and generous with his community in his knowledge and insights. Everyone who knew Steve remembered him as one of the brightest individuals they knew, as well as one of the most honest.

EB: Any plans for further publications?

DA: I have worked on and hope to finally publish a comprehensive biography of Milt. In recent years, concepts like “antifa” and the use of WW II metaphors to describe our political moment have reminded me of Steve and Milt’s struggle with political conflict both in their personal fight, while also a struggle to rise above ideology. Steve and I began our discussions about Milt during Bernie Sanders’ campaign for the Democratic nomination during the 2016 Presidential election. What Steve heard in Sanders was both a callback to the kind of Old Left rhetoric that Milt intoned, while identifying Sanders as exactly the kind of guy Milt was frequently skeptical of in the 1960s. The constant war between ideas and the yearning to carve out one’s place in the pantheon of “the good fight” remains a potent issue.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

DA: Thank you.

Follow

Follow