Sandra Scofield is the author of seven novels, including Beyond Deserving, a finalist for the National Book Award, and A Chance to See Egypt, winner of a Best Fiction Prize from the Texas Institute of Letters.

Sandra Scofield is the author of seven novels, including Beyond Deserving, a finalist for the National Book Award, and A Chance to See Egypt, winner of a Best Fiction Prize from the Texas Institute of Letters.

She has written a memoir, Occasions of Sin, and a book of essays about her family, Mysteries of Love and Grief: Reflections on a Plainswoman’s Life. She is also the author of The Scene Book: A Primer for the Fiction Writer and in the fall Penguin will release her book The Last Draft: A Novelist’s Guide to Revision.

We sat down on the internet to talk about her new book of short stories, Swim: Stories of the Sixties, just released by Ashland’s Wellstone Press.

EB: Swim is a trilogy of stories about a twenty-something woman who negotiates dangerous travel—hitching, crashing at the ranch of a bullfighter in Mexico, and with two young soldiers on leave in Mykonos. How did you come to write the stories?

SS: Each one began in a different way. All took years of brooding, sketching, writing, fussing. Still, I think a story always starts with an image or impulse you can’t escape. In the case of these stories, those images became part of who I am, and as I slipped into old age I saw my young self with great empathy; I wanted to figure her out. A friend had saved my hundred+ letters to her during the 60’s, and in 2005 she gave them to me. (I’m going to be posting some on my website starting in July: sandrajscofield.com) They are packed with detailed observation and also with a naive, passionate, earnest scavenging for stories. In my letters–and they are long–everything is a story. I was keeping a journal, writing those letters, and, I think, memorizing a lot of life as I lived it. I can’t say what a gift her stewardship and generosity is.

More specifically, I’ll tell you that “Swim” began as an extension of my Mykonos notes that I brought back; I worked on them in 1968, when I was studying theatre in Illinois. Some years later I tried a story. But it wasn’t until a few years ago that I picked up those old efforts and saw what the story was, and that the soldiers’ stories were the vehicle for it.

“An Easy Pass” was clearly an outgrowth of the dozens of letters from Mexico, full of detailed observations, and also an almost hysterical fascination with bullfighters (especially the young beginning ones). I had done a lot of what I think of as “younger” Mexico stories. They are archived. I did one a few years ago for Image, too.

“Oh Baby Oh” was in a way the most personal of the stories, because it arose not just out of some experience (none of the stories are “true”) but some thread of resentment toward a whole string of young men who wanted to advise me on how to be a better person.

In the last couple of years I found myself going back to the stories, fussing with them, and, if I can say this, falling in love with them in a way I never have with a story before. I longed to see them between covers, and I asked Jonah to read them and tell me what he thought. His enthusiasm was such a relief!

EB: The main character, who is called Baby, keeps a writer’s journal and carries a copy of The Stranger. It makes me wonder what pieces of your own experiences might be reflected in her stories—and how she is like the younger you?

SS: Well, sure, I kept a journal and carried Camus around. (I just read Alice Kaplan’s Searching for the Stranger, a kind of biography of The Stranger; it’s a marvelous read.) And I had a “fall” when my hair was growing out. (Ouch.) I hitchihiked from NYC to SF. I don’t think I was capable of just being, just doing; I always had to interpret life, day to day. At the heart of all my ruminations was my conviction that no one understood me, which is probably true, since I didn’t either. Guys either liked me or couldn’t stand me, based, I think, on my own attraction to them. If I didn’t like a guy–jocks, slick guys, big shots, etc.–I was snotty. I felt that all relationships, friendships, however short or long, were my choices. I didn’t think I was pretty but I could get a guy talking about things he’d never thought about before. And I was joyful, eager. I didn’t expect anything in return; sex was never a negotiation in my mind. I suspect I shocked a lot of boys–well aren’t they boys, in college?–because I also brought a lot of joy, a sense of fun, a freedom to sex and friendship. I was never seduced; nobody could make me do what I didn’t want to do before they even thought of it. I felt superior but on the other hand I was kind of generous. I wasn’t looking for any kind of attachment. I lived with someone in Chicago because I was broke, but regretted it. I wouldn’t say I had a real boyfriend, a real lover, until I met my first husband in a crazy sort of accident in Ithaca NY. I was in an acting troupe at Cornell, and Al had come to see an old Coast Guard buddy who lived in my house. We were like magnets. My whole life went off-track and it was years before I had any kind of stability, but those years with him were the electrical storm of my life. I wrote about him in Mysteries of Love and Grief, which is made up of essays, and he’s the basis for “Fish” in my novel Beyond Deserving, which was a NBA finalist, but mostly I’ve kept him to myself. For one thing, I’ve been happily married since 1975 to a man I wouldn’t dream of writing about. I wouldn’t want to analyze us or betray his privacy. And I think my stories are all far in the past. My present life is totally mundane, happily so.

EB: Many of the characters—not all, but many, seem on the verge of losing their innocence and learning to make their way in the world. For me, Baby seems most aware in the middle story, “An Easy Pass.” What trajectory did you in mind for the order of the three pieces?

SS: I knew “Swim” was last because I wanted its ending to end the book. The other two? I agree about your assessment, but I had “An Easy Pass” first until Jonah suggested we switch the first two stories. I took his advice and came to agree completely.

EB: The prose of the stories is taut—and especially the sentences, which ironically reminded me of Hemingway. Your sentences create a unique, almost aerobic, pace to the stories and I found myself wondering about the craft of these. Do you sometime revise a sentence several times until it feels just right?

SS: I think the story is in every sentence. And every sentence leads to the next. It’s slow work. Deliberate, and largely aural. Remember I’m of an age of reader who grew up on long novels with beautiful prose, lot of winding sentences in some, taut in others. I would never think of Hemingway as kin to me, but I adored James Salter’s work and feel he had an influence on me. As did Camus. Mavis Gallant. Jane Bowles. Jean Giono. Robert Stone. Rebecca West. And remember I grew up Catholic–boarding school Catholic–and language was a huge part of the practice of Catholicism, and of expectations of Catholic school students.

EB: I was intrigued by the stylistic choice you made not to signal dialogue with quote marks or italics. That seemed to signal remembered speech to me, or some attempt to disorient the reader. Did you have something particular in mind?

SS: You seem to have identified my intention well. In a way, everything is a dream, a fiction; the stories are outside of time; in another way, Baby doesn’t connect with anyone, and dialogue is connection. I certainly wasn’t trying to be precious or anything; it just felt inevitable and right.

EB: The nineteen sixties seems to be perpetually interesting to readers—both those who lived them and those who know them from history. What is the attraction of the sixties?

SS: It’s wild, isn’t it! All of a sudden, SIXTIES books–from the New Yorker, from the New York Times, and others. I just got the New Yorker one and am reading James Baldwin, whose great essay, “Letter from a Region in My Mind” blew the lid off the staid New Yorker. I guess there are lots of us with roots in that time. I also think something about the awful politics right now sends us back to the conflicts and inventions of the sixties. It was exciting to be young then, and scary, too. Baby, of course, isn’t involved.

EB: Looking at the cover art. “The Weight of Water,” by southern Oregon artist Abby Lazerow reminded me that you are also a painter. Is your painting like your writing?

SS: Ed, that is a wild question. I’ve never considered it. Maybe. I don’t follow many rules, but I spent a couple of years learning them. I’m more interested in color than in form. I like certain kinds of precision, and then I love wildly free gestures, too. Every painting is a discovery. I have an idea, I might even be working from a photograph, but no painting ever turns out like something I imagined or planned. Don’t misunderstand: I consider myself to have a lot of deliberateness, of control, but I like to break it open at some point. I’m much influenced by British Modernists like Ben Nicholson, Christopher Wood, Joanna Carrington, Mary Fedden, Margaret Mellis. Lots of wit and freedom and interpretation of what is apprehended. I’m making a second trip to St. Ives to paint in October, and will do a workshop on the Modernist landscape.

I started so late, I had to make a choice: settle on a style and try to get deft at it; or widen my range, and reach for discovery, luck, freedom. So now that I think about it, I’d say I’m a hell of a lot more controlled as a writer than as a painter. But as a writer, I’m still not willing to follow many rules. And by the way, one thing I love about painting is that THERE ARE NO WORDS.

EB: You are also coming out with a book The Last Draft about revision. Can you tell us a little about that?

SS: December, from Penguin. It would have been dead in the water if I had called it: Sandra’s Poetics of the Novel, but that’s a lot of what it is. It’s what I’ve learned the hard way. Nobody taught me to write a novel. I never took a novel workshop or class. I don’t have an MFA. I learned to write by reading, by writing, by revising. So I decided that if the world needed anymore writing books, one would be on revision of the novel. I think of myself as speaking one to one to the reader, a kind of coach and cheerleader; I mean to be encouraging and demystifying, but I’m also serious. There’s a lot in that book. It’s really step by step how to describe what you wanted to do in your first draft, and how you tried for it; how to analyze what’s strong and what’s not in that first effort; a deepening of your vision and your sense of direction; a plan for redoing or integrating old material with new writing. It all comes from my teaching and analysis of how my instruction and exercises and guidance worked. Kisses to my students! Someone could sort of whip through the explanations and exercises and do a revision. Or someone who really wants to be a writer could use it as a guide to a whole journey of learning. Janet Burroway very generously said of it, “We need this book.” I guess that’s what I thought, after over twenty years of working with aspiring novelists. Now I’m trying to write a new novel and all I write rings in my ears! It’s helpful, yes; it’s also humbling. Writing a novel is huge and hard.

SS: December, from Penguin. It would have been dead in the water if I had called it: Sandra’s Poetics of the Novel, but that’s a lot of what it is. It’s what I’ve learned the hard way. Nobody taught me to write a novel. I never took a novel workshop or class. I don’t have an MFA. I learned to write by reading, by writing, by revising. So I decided that if the world needed anymore writing books, one would be on revision of the novel. I think of myself as speaking one to one to the reader, a kind of coach and cheerleader; I mean to be encouraging and demystifying, but I’m also serious. There’s a lot in that book. It’s really step by step how to describe what you wanted to do in your first draft, and how you tried for it; how to analyze what’s strong and what’s not in that first effort; a deepening of your vision and your sense of direction; a plan for redoing or integrating old material with new writing. It all comes from my teaching and analysis of how my instruction and exercises and guidance worked. Kisses to my students! Someone could sort of whip through the explanations and exercises and do a revision. Or someone who really wants to be a writer could use it as a guide to a whole journey of learning. Janet Burroway very generously said of it, “We need this book.” I guess that’s what I thought, after over twenty years of working with aspiring novelists. Now I’m trying to write a new novel and all I write rings in my ears! It’s helpful, yes; it’s also humbling. Writing a novel is huge and hard.

EB: Any final words of advice for writers?

SS: I don’t know that this is advice, but I want to say that not everyone is going to write a bestseller and even a big house paying a lot can’t make it happen very often. The work of writing is going to be happy if it makes you happy to do it. What happens next is a big duck shoot. With “Swim” I knew I wanted to work with Jonah because I knew he loved my writing and these stories and I knew we would be a great team. I chose to publish with a small press without trying for a big one, and it’s been more fun, more productive, happier than any experience I’ve had in publishing. I hope readers will buy my book and tell others about it but I’m not putting a kid through college on the proceeds. If we made a little money I’d probably do another book this way. More Stories from the Sixties, anyone?

EB: Thanks for talking with us. It’s good to have you back in the area.

SS: This is so nice. I think what a writer really really wants is for someone to want to talk about her stories!! So here we are.

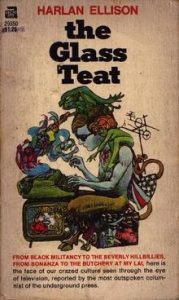

I read more Harlan Ellison, graduating to the Dangerous Visions collection and Again Dangerous Visions, with their equally abrasive introductions. I was cheering from the sidelines when Ellison wrote “City on the Edge of Forever.”

I read more Harlan Ellison, graduating to the Dangerous Visions collection and Again Dangerous Visions, with their equally abrasive introductions. I was cheering from the sidelines when Ellison wrote “City on the Edge of Forever.” The dinner, which included Harlan, my wife and me, and a half dozen students went pretty much as you might expect. Harlan argued with the students about just about everything. I sat at the far end, sipping a beer and keeping my head down. I remembered the story about Irwin Allen.

The dinner, which included Harlan, my wife and me, and a half dozen students went pretty much as you might expect. Harlan argued with the students about just about everything. I sat at the far end, sipping a beer and keeping my head down. I remembered the story about Irwin Allen.

Follow

Follow