Christina Ward is an award-winning writer and editor. She is a featured contributor to Serious Eats, Edible Milwaukee, The Milwaukee Journal/Sentinel, Remedy Quarterly, and Runcible Spoon magazines. She makes regular guest food expert on television and public radio and in 2017 published Preservation: The Art and Science of Canning, Fermentation and Dehydration with Process Media, Inc.

Christina Ward is an award-winning writer and editor. She is a featured contributor to Serious Eats, Edible Milwaukee, The Milwaukee Journal/Sentinel, Remedy Quarterly, and Runcible Spoon magazines. She makes regular guest food expert on television and public radio and in 2017 published Preservation: The Art and Science of Canning, Fermentation and Dehydration with Process Media, Inc.

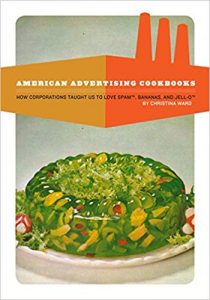

Her second book, American Advertising Cookbooks: How Corporations Taught Us To Love, Spam, Bananas, and Jell-O was released in January of 2019.

Ed Battistella: Congratulations on American Advertising Cookbooks, which I am really enjoying. How did you get interested in the history of promotional cookbooks?

Christina Ward: I’m the Master Food Preserver for my county; which means that I’m charged by the State to teach the most up to date scientifically proven methods of food preservation. I’m also a book collector with a love of history. All my interests began to converge during the research of my first book, Preservation-The Art and Science of Canning, Fermentation, and Dehydration.

My research into the history of preserving food leads me to the very interesting (to me at least—and now I hope readers!) place in American history where technology, food, immigration, and marketing all came together to create and define American cuisine. Promotional cookbooks represent the culmination of all those influences in a neat, garishly printed booklet.

EB: I was also fascinated by the role of home economics. What’s the story there? How did education and domestic science affect taste-making?

CW: The birth of Home Economics was a tangent of the Suffragette movement of the late 1800s that was, interestingly, heavily influenced by a very conservative cultural Protestantism. The women who advocated for equality made the case that the “domestic sciences” were of the same value as chemistry or biology. In an age where there was just the barest of understanding of food science and where women were barred from studying in universities, domestic science became a way for women to become both educated and independent.

Because the curricula were developed by a small group of foremothers who agreed on techniques and recipes for the most nutritional cooking, a sameness was spread across the country. At the same time, printing technologies advanced to allow for cheap and accessible books. Any home economist worth her salt and with a smidge of regional fame soon wrote a cookbook. This too helped spread recipes and ideas about what a “proper” cook should be doing in the kitchen.

EB: A lot of the food you mention I recalled from my youth, but I totally missed ham banana rolls. Can you explain the rise of bananas.

CW: Bananas tell a great story. They’re a relatively “new” food and wholly brought to consciousness by advertising. All food processing companies in the 1930s hired the newly minted domestic scientists to concoct recipes featuring their products. United Fruit just did it very very well. Ham banana rolls were introduced in 1941 (I think!) and featured a couple of food trends of the time. Firstly, white sauces!

In the first part of the 20th Century, starvation or at least the fear of it was very real. Food supplies were dependent on mostly local purveyors while the financial collapse of the 1930s meant people actually starved. Paramount to food educators was increasing the total caloric intake of workers. (How different we are today!) The solution to boosting the Kcal of any and every dish is slathering it with a flour-based cream sauce or better yet, cream and cheese sauce! Sliced ham was a cheap protein and bananas were the star of the recipe, and voila! Ham banana rolls. The actual recipe has its roots in Pacific island cooking where pork served with plantains is found.

It also pays to remember that just because these recipes appeared in an advertising cookbook, doesn’t mean that they tasted good or people adopted them! For every successful Green Bean Casserole (invented by Campbell’s Soups) there is a stinker of a recipe; those are the ones that tend to bring us a laugh.

EB: Is there a particular food that in your mind typifies the role of advertising and advertising psychology in developing our tastes. Do you have a favorite example?

CW: Orange juice! It’s about 100 years from its introduction to the national markets via advertising and how many generations consider it a morning staple. Why? Sunkist, a company that began as a consortium of Florida orange growers, worked very hard to create advertising that touted the health benefits of drinking the juice of oranges. Why not eat the whole orange? Because it was cheaper to extract the juice and can it than the cost of shipping fresh oranges.

EB: Why are we so easily manipulated by advertising, do you think?

CW: Advertisers were the first to adopt and adapt the new-fangled psychological theories of the early 1900s—the ideas of subconscious and motivation—that could not just make a product stand out but create actual demand. There is something about the human psyche that wants to want. Advertisers play upon that aspirational need.

EB: I was struck by the wonderful images in the book. Where did you find them all?

CW: So many cookbooks! I’m a collector, and I was lucky enough to inherit my mother-in-law’s pristine collection of advertising cookbooks. She didn’t keep them as a collection per se, but as a Depression-era housewife hung on and used those cookbooks throughout her life. I’m even luckier in that she kept them in meticulous condition. These are, with a few exceptions, printed on flimsy paper with cheap inks and processing. They were intended to be used and not really kept for over 70 years.

CW: So many cookbooks! I’m a collector, and I was lucky enough to inherit my mother-in-law’s pristine collection of advertising cookbooks. She didn’t keep them as a collection per se, but as a Depression-era housewife hung on and used those cookbooks throughout her life. I’m even luckier in that she kept them in meticulous condition. These are, with a few exceptions, printed on flimsy paper with cheap inks and processing. They were intended to be used and not really kept for over 70 years.

Those formed the bulk of the images in the book. I have a few friends who share my fervor for advertising cookbooks who lent some gems for scanning.

EB: You have a collection of cookbooks. Can you tell us about that?

CW: Cookbook collectors are sub-species of bibliomaniacs! I collect them first and foremost because I love them. But deeper than that, cookbooks are history. The story of what we eat and why is fascinating and informed by so many different events; cookbooks reflect an ideal self, that one cook’s vision of a perfect America in each and every volume.

EB: What was the most surprising thing you learned about food and marketing?

CW: The most surprising thing would be how short our cultural memory is. Recipes that many folks think were invented by grandma came from an advertising cookbook. Interestingly, recipes in and of themselves cannot be legally copyrighted, so publishers tended to pass along and tweak a core group of recipes. If you look at the bulk of the cooking from the 1930s to the 1970s, before Julia Child brought French techniques back to American kitchens, there is a sameness in most of the dishes. That sameness comes from the standardization of processed ingredients.

EB: Where can readers get ahold of your book?

CW: Publisher Process Media is an independent publisher with international distribution, which means that every indie bookseller in the US and Canada can get it for you. Larger shops like Barnes & Noble and of course, Amazon, both stock the book.

EB: You’ve also written about canning, fermentation, and dehydration in your 2017 book Preservation. Any future food-related projects on your plate?

CW: I still teach classes! It’s fun to lead a group of people in community food preservation projects. I get a great deal of pleasure from seeing people ‘get’ it and then take those new found skills home. As to writing, I’ve got a few new projects, but I’ll hold off talking about them until they’re closer to completion; I’m a bit superstitious that way.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

CW: Thank you for the opportunity to share my crazy obsession!

Follow

Follow

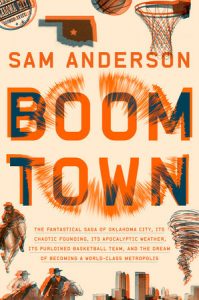

EB: Can you tell us about the title? The book seems to resonate with booms, literal and metaphoric.

EB: Can you tell us about the title? The book seems to resonate with booms, literal and metaphoric.

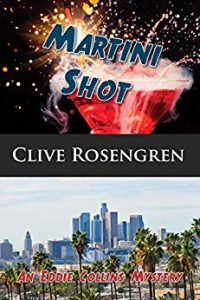

South Dakota native Clive Rosengren is a veteran actor with stage, screen and television credits that include the Great Lakes Shakespeare Festival, Ed Wood, Twin Peaks, and Cheers. He is the author of four novels featuring actor/private investigator Eddie Collins:

South Dakota native Clive Rosengren is a veteran actor with stage, screen and television credits that include the Great Lakes Shakespeare Festival, Ed Wood, Twin Peaks, and Cheers. He is the author of four novels featuring actor/private investigator Eddie Collins:  Sharon Dean grew up in Chelmsford, Massachusetts, received a PhD from the University of New Hampshire, taught at Rivier University in Nashua, New Hampshire. Having written four academic books as a professor, she has reinventing herself as a writer of mystery novels. Her thought provoking whodunits featuring literature professor Susan Warner include

Sharon Dean grew up in Chelmsford, Massachusetts, received a PhD from the University of New Hampshire, taught at Rivier University in Nashua, New Hampshire. Having written four academic books as a professor, she has reinventing herself as a writer of mystery novels. Her thought provoking whodunits featuring literature professor Susan Warner include  Sharon: What motivates you to keep writing in an era when so many good novels like yours don’t get the notice they deserve?

Sharon: What motivates you to keep writing in an era when so many good novels like yours don’t get the notice they deserve?

Clive: Do you do a detailed background on your characters? Or do you pattern them after people you have known?

Clive: Do you do a detailed background on your characters? Or do you pattern them after people you have known?

Kayla Bush is a 2013 graduate of Southern Oregon University with degrees in English and Theatre Arts. She taught in China from 2015 – 2016.

Kayla Bush is a 2013 graduate of Southern Oregon University with degrees in English and Theatre Arts. She taught in China from 2015 – 2016.