TOD DAVIES is the author of The History of Arcadia series: Snotty Saves the Day, Lily the Silent, The Lizard Princess and now Report to Megalopolis: The Post-modern Prometheus, which Kirkus Reviews called “A philosophical fable.”

TOD DAVIES is the author of The History of Arcadia series: Snotty Saves the Day, Lily the Silent, The Lizard Princess and now Report to Megalopolis: The Post-modern Prometheus, which Kirkus Reviews called “A philosophical fable.”

Tod Davies is also the editor/publisher of Exterminating Angel Press and Exterminating Angel Magazine. She lives with her husband, the filmmaker Alex Cox, and their dogs in Colestin, Oregon.

Tod is also the author two cooking memoirs Jam Today: A Diary of Cooking With What You’ve Got and Jam Today Too: The Revolution Will Not Be Catered.

Ed Battistella: Report to Megalopolis is book four in The History of Arcadia series. Can you give our readers a quick orientation to the world you’ve created in Snotty Saves the Day, Lily the Silent, and The Lizard Princess?

Tod Davies: Arcadia is a land surrounded on three sides by a huge, technocratic, decayed, and power hungry world. How does it maintain itself and evolve? Or does it go under, swallowed up by the greater power? That’s what we’re exploring in all of the books. Arcadia was literally formed by someone discovering who they truly were—and acting on it. The first three books are about how the characters struggle to preserve the values that make Arcadia what it is. The fourth book, though, is told by a character who despises those values, and seeks to replace them with an imperial structure based on the rule of the powerful—with himself at the top, of course.

EB: Readers can read Report to Megalopolis without going back to the earlier books, it seems to me. Did you have this in mind as a stand-alone tale?

TD: Yeah, absolutely. Actually, I like to think they’re all stand-alone books—but there’s a rhythm, and maybe some more deep satisfaction in reading all of the books. The same heart, from multiple points of view. I love writing that. Why do individuals think/feel/see the way they do, so differently about the same landscape? How does that interact with other viewpoints to form our collective story? What is the responsibility of the individual doing the seeing, and the acting that comes out of that seeing?

EB: The subtitle is “The Post-modern Prometheus.” How much was Frankenstein on your mind as you were writing Aspern Grayling’s story?

TD: By the last few drafts, completely. It’s weird, hardly anyone notices that Shelley’s monster is the sympathetic one—denied love, denied warmth, denied common humanity. Then he turns against all love, warmth, humanity. We see that happening in our own world when we objectify our fellow human beings, turning them into statistics. Like the historian who said that things are getting better because, percentage wise, fewer people are being tortured and murdered than ever before in history! Wonderful news. What he doesn’t mention is that the numbers are astronomically higher than in the past. But since populations have grown, the percentage is less. You think all those people, our fellows, being tortured and murdered don’t have an effect on the rest of us? Dream on. You know the joke about the kid who’s on a beach littered with thousands of stranded starfish? He doggedly throws them back, one by one, when some guy mocks him—“What good is THAT doing?” Kid just heaves another one in, and says, “It did some good to THAT one.” Arcadia means to build a pattern out of that vision.

EB: There seem to be other dystopian and fantasy influences as well. What other works inform the story, do you think?

TD: Oh, Ursula K. LeGuin’s Earthsea tales, of course. All her work is about the treasure of being human, and the responsibility to support our fellows in their human needs and values. C.S. Lewis, same reason, and for his principled love of fairy tales. Tolkien. His yearning for a more human world is palpable. Octavia Butler’s Kindred. Her understanding of the suffering that comes from trying to be more than human—how it leads to being worse than less. Proust. His whole oeuvre is one long fairy tale, about the transformations that happen to human beings, and how we’re blind to them—as if they’re formed in a world outside of our blinkered vision. A world like Arcadia, in fact.

TD: Oh, Ursula K. LeGuin’s Earthsea tales, of course. All her work is about the treasure of being human, and the responsibility to support our fellows in their human needs and values. C.S. Lewis, same reason, and for his principled love of fairy tales. Tolkien. His yearning for a more human world is palpable. Octavia Butler’s Kindred. Her understanding of the suffering that comes from trying to be more than human—how it leads to being worse than less. Proust. His whole oeuvre is one long fairy tale, about the transformations that happen to human beings, and how we’re blind to them—as if they’re formed in a world outside of our blinkered vision. A world like Arcadia, in fact.

EB: Traditional fairy tales, before they were Disneyfied, had a lot of brutality and ruthlessness. Was Report to Megalopolis a bit of an homage to the origins of the genre?

TD: Oh yeah. More than an homage, I like to think it’s in lineal descent! Fairy tales talk about who we really are. I mean REAL fairy tales. For example, “Donkey Skin” is about a father preying on his daughter. There are predatory fathers everywhere, probably without letting themselves be conscious of what they are doing to their daughters. Fairy tales have known about a father’s incestuous preying on his daughter for centuries. But it’s only coming out now into our common discourse. Woody Allen would not have surprised the tellers of fairy tales. Neither would Report’s Pavo Vale and his desire for his own granddaughter. A very fairy tale subject.

EB: Report to Megalopolis has a lot going on and the narrative captures Aspern Grayling’s confessional voice and his emotions as well, which I imagine was a challenge to craft. What was the most difficult part of writing this book?

TD: Oh gosh. The memory of it is still raw. The most difficult was letting his real pain break through. Man, that was tough. I think that if you read an earlier draft, you’d know I was trying then for a lighter, almost cardboard villain, touch. But the more I wrote, the more I suffered, and the more I knew I was suffering his pain at not allowing himself to be human. That’s happening everywhere, you know. It was happening to me when I was writing the earlier drafts without wanting to go deeper. People deny their humanity because they think that makes them ‘good’ or ‘successful’, or at the very least, comfortable, and then when it pains them, they blame those they have refused connection with—Aspern’s tortured love for Devindra is an example of that. His twisting and turning to get away from any self-knowledge that would force him to understand who he truly is. That he is as weak and subject to human laws as anyone. Contempt is a powerful defense against one’s own weakness. But that defense causes unlimited suffering. And I realized with this book that was what I was writing about, and will write about: how we defend against our own vulnerabilities, and in fighting them, destroy what happiness we, and others, could have. What a godawful waste.

EB: Pavo Vale, the monster, is misogynistic to say the least. Was this aspect inspired or spurred along by the #MeToo Movement?

TD: It’s funny, you know the RESIST image that Mike Madrid created for the earlier books—that was way before the #Resistance movement, but totally in tune with it. Same with the #MeToo movement. All of Arcadia, in the very first book, is formed by a horrible little boy realizing he has given up all his female values to ‘succeed’. And the #MeToo movement is about not having to harden yourself against the sufferings of your sisters in order to get ahead in the pecking order that, up till now, was unconsciously and exclusively built with solely ‘male’ values: dominance, hierarchy, power plays, endless growth. You had to pretend you weren’t being abused if you wanted to get ahead. That’s over now. Arcadia is fighting that battle against Megalopolis. Softness, kindness, commonality: these are not weaknesses. These are strengths.

EB: You teased us with hints about the Evolutionaries. What can we expect in book five of The History of Arcadia series?

TD: Isabel the Scholar kept talking to me, and coming into Report when I least expected it—the voice of the younger generation, the new Evolutionaries, who are forming a new pattern and a new story in the hopes that will preserve and expand the values of Arcadia. Revolution doesn’t work. It needs the opposing side to exist, inevitably strengthening what it fights. The only hope, my young characters feel, is a leap in evolution. And Isabel is a scientist of evolution. I love her. She is my heroine, even though her dearest friend Shanti is the glamorous one. Shanti knows Isabel’s worth. And Shanti and Isabel are going to be grappling with the next great problem Arcadia faces after Pavo Vale has invaded: how to make human what has been created to be inhuman. Which is the problem we all face. Yep. We all face that problem now. I’m thinking of asking Mike Madrid, who does all the Arcadian artwork since the second book, to change the RESIST image to PERSIST.

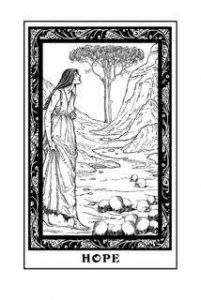

EB: Can you tell us a little about the artwork that accompanies the book?

TD: Mike Madrid, who does all the Exterminating Angel Press design, as well as being one of its authors (The Supergirls), has done the illustrations for the last three Arcadia books. I can’t say enough about Mike—he always comes up with design ideas that push me to go further, even when I’m writing the earlier drafts. A good example of that is the Luna deck. He’d come up with a few Luna cards, and the next thing I knew, the Luna was a huge part of Arcadian culture. We needed an appendix to discuss it, written by Devindra Vale!

TD: Mike Madrid, who does all the Exterminating Angel Press design, as well as being one of its authors (The Supergirls), has done the illustrations for the last three Arcadia books. I can’t say enough about Mike—he always comes up with design ideas that push me to go further, even when I’m writing the earlier drafts. A good example of that is the Luna deck. He’d come up with a few Luna cards, and the next thing I knew, the Luna was a huge part of Arcadian culture. We needed an appendix to discuss it, written by Devindra Vale!

And in this book, my own dear husband, the filmmaker Alex Cox, drew a few maps as if he were Aspern sketching them out—I think they help orient the reader. I’ve always been blessed to have great collaborators nearby.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

TD: Thank you, Ed. And, speaking of great collaborators, thank you for being an essential part of the fast evolving literary world here in Cascadia.

Follow

Follow