Sharon L. Dean grew up immersed in the literature of New England. She taught writing and literature at Rivier University in New Hampshire, where she lived until moving to Oregon.

Sharon L. Dean grew up immersed in the literature of New England. She taught writing and literature at Rivier University in New Hampshire, where she lived until moving to Oregon.

After giving up writing scholarly books that required footnotes, she became a writer of mysteries. Her first mystery series features retired professor Susan Warner and her second features librarian sleuth Deborah Strong. Between the two series, Dean published a stand-alone novel, Leaving Freedom. In it, thirty-year-old Connie Lewis sees only irony in the name of the town where she grew up, Freedom, Massachusetts. The novel follows Connie from Massachusetts to Florida and Oregon. A sequel, Finding Freedom, will be published by Encircle Publications in June, 2023. It will bring Connie, now eighty years old from Oregon back to Freedom.

Recently, Dean published a collection of short stories titled Six Old Women and Other Stories.

Ed Battistella: I enjoyed reading the stories in Six Old Women which all about about the secrets we keep with us as we age. What prompted you to write about secrets?

Sharon Dean: I remember that when I reached adulthood, my mother told me some of the secrets about people in the small town where I grew up. It’s said that in New England “people don’t air their dirty laundry in public.” That doesn’t mean there isn’t some lurking along with the skeleton in the closet.

EB: You mentioned that the title story, Six Old Women, came from an idea you and your college roommates once had about all living together in a lakeside commune when you were older. Are the characters based on your erstwhile roommates?

SD: Actually, we gathered on the seacoast in Maine. The houses are part of the setting of my Deborah Strong novel, Calderwood Cove. The island in Six Old Women is imagined, but I know the setting of New Hampshire’s Lake Winnipesaukee well. I like to visualize houses, so the one in Six Old Women is designed after a house where I vacationed on the Massachusetts seacoast. Characters based on my roommates? Not if I want to keep them as friends. Seriously, the characters are all imagined.

EB: You’ve written both novels and short stories. Do you have a preference for one form over the other? Or does it depend on the story?

SD: I like both. It depends on the story. Even when I was writing papers in college, my feeling was that when it’s done, it’s done. I actually have trouble writing a novel much longer than 65,000 words. I don’t like to pad my fiction.

EB: I’ve always enjoyed your mystery novels. The stories in Six Old Women aren’t mysteries but they are mysterious. Did your experience writing one type of story find its way into these, or is life just mysterious?

SD: I published an article on this in Mystery and Suspense Magazine called “The Classics are Mysteries, too” (March 28, 2022). I also recently posted a guest blog on the subject in Writers Who Kill (January 21, 2023). As different as it is from science, fiction seeks “the answer to the riddle of the universe.” Life is, indeed, mysterious.

SD: I published an article on this in Mystery and Suspense Magazine called “The Classics are Mysteries, too” (March 28, 2022). I also recently posted a guest blog on the subject in Writers Who Kill (January 21, 2023). As different as it is from science, fiction seeks “the answer to the riddle of the universe.” Life is, indeed, mysterious.

EB: I thought of these stories as fast-paced psychological studies. How did you manage pacing as a writer?

SD: I’m glad you read them that way. I’ve always been more interested in the setting and the psychology of a character than in the plot. My wonderful critique group, Monday Mayhem, helps me move the plot along. They remind me not to over-analyze, to avoid “fact dumps,” to use dialogue. Kudos to Carole Beers, Clive Rosengren, Michael Niemann, and Jenn Ashton.

EB: Are the other stories—”Shuffleboard,” “Hardscrabble,” “Pavlov’s Puppies,” “The Man Who Loved Cribbage”–based on real incidents? New Hampshire is starting to seem like a scary place.

SD: No real incidents, but definitely real settings. They indulge my nostalgia for New England. I used to vacation with my cousin at a place where we always played shuffleboard, I skied the Hardscrabble trail on Cannon Mountain many times, and the recluses in “Pavlov Puppies” and “The Man Who Loved Cribbage” live in houses whose exteriors are much like ones in my town. Is New Hampshire scary? Not in my experience, but I confess that I was a child who imagined monsters under my bed.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

SD: Thank you for having me. I’m glad that Literary Ashland lives on this blog even though it’s no longer live on the radio.

Follow

Follow

JF: Trying to explain or deconstruct the power of an artwork, let alone a religious artwork, is a fool’s errand (for example, one can’t say in words why a Bach chorale is inspirational). But I have always loved both history and research. What I found most interesting about Icons is that they play a role similar to sacraments in western religion whereby the icon is an intercessor—a window—to help the believer communicate with God. The Icon thus becomes extraordinarily powerful and I wanted to put that power in the political realm and see what happened. The results proved to be explosive.

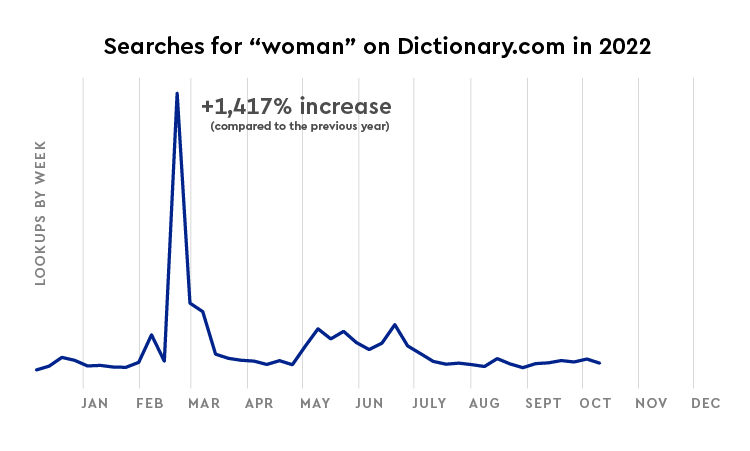

JF: Trying to explain or deconstruct the power of an artwork, let alone a religious artwork, is a fool’s errand (for example, one can’t say in words why a Bach chorale is inspirational). But I have always loved both history and research. What I found most interesting about Icons is that they play a role similar to sacraments in western religion whereby the icon is an intercessor—a window—to help the believer communicate with God. The Icon thus becomes extraordinarily powerful and I wanted to put that power in the political realm and see what happened. The results proved to be explosive. The American Dialect Society is not the only word of the year around.

The American Dialect Society is not the only word of the year around. You can look it up

You can look it up  Jon Raymond is the author of the novels The Half-Life, Rain Dragon, and Freebird, and the story collection Livability, winner of the Oregon Book Award. He was the editor of Plazm Magazine, associate and contributing editor at Tin House magazine, and a member of the Board of Directors at Literary Arts. He lives in Portland.

Jon Raymond is the author of the novels The Half-Life, Rain Dragon, and Freebird, and the story collection Livability, winner of the Oregon Book Award. He was the editor of Plazm Magazine, associate and contributing editor at Tin House magazine, and a member of the Board of Directors at Literary Arts. He lives in Portland. JR: I wanted him to be pretty likable. Otherwise, who cares if he gets caught and unmasked or not? So I made him a fairly sophisticated, possibly even somewhat repentant representative of the petrol-empire. In particular, I made him a Sunday painter in the style of LBJ or George W. Bush, two war criminals who found their artistic muses after their retirements from death-dealing. It’s a good tactic, it turns out. People forget what you did while you were in power while they’re looking at your paintings.

JR: I wanted him to be pretty likable. Otherwise, who cares if he gets caught and unmasked or not? So I made him a fairly sophisticated, possibly even somewhat repentant representative of the petrol-empire. In particular, I made him a Sunday painter in the style of LBJ or George W. Bush, two war criminals who found their artistic muses after their retirements from death-dealing. It’s a good tactic, it turns out. People forget what you did while you were in power while they’re looking at your paintings.