Jeffrey Max LaLande, photo by Lee Webb

For over 30 years, Jeff LaLande worked as an archaeologist and historian for the U.S. Forest Service in Medford. During many of those same years he taught history and anthropology courses as an adjunct professor at Southern Oregon University. He has served on Oregon’s State Advisory Committee on Historic Preservation, the editorial board of the Oregon Historical Quarterly, and on other boards. He is one of the editors-in-chief of the Oregon Encyclopedia.

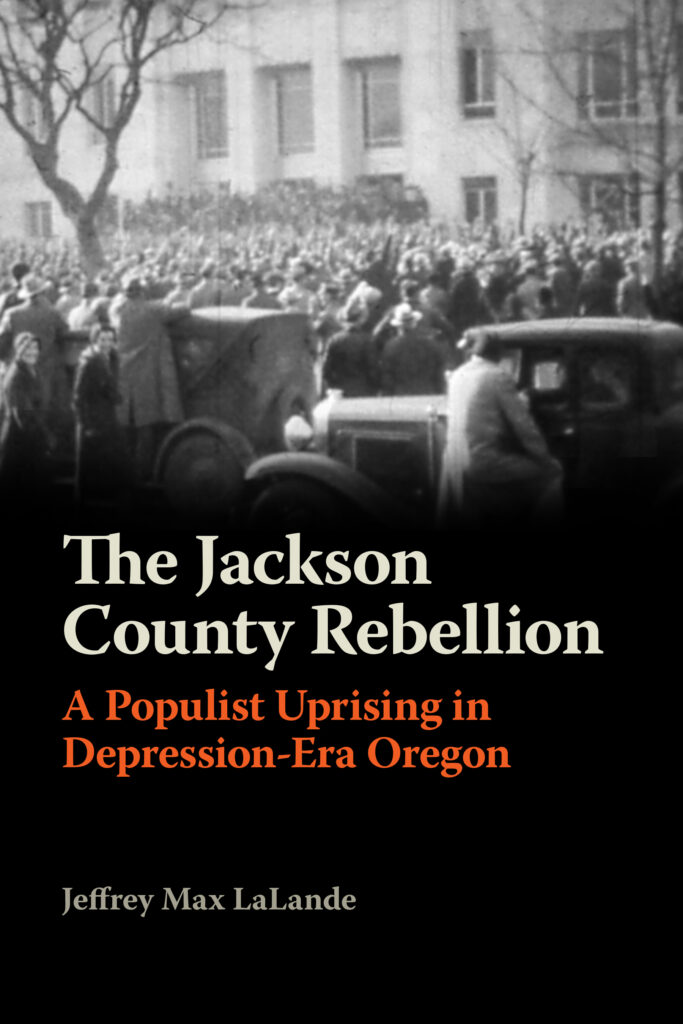

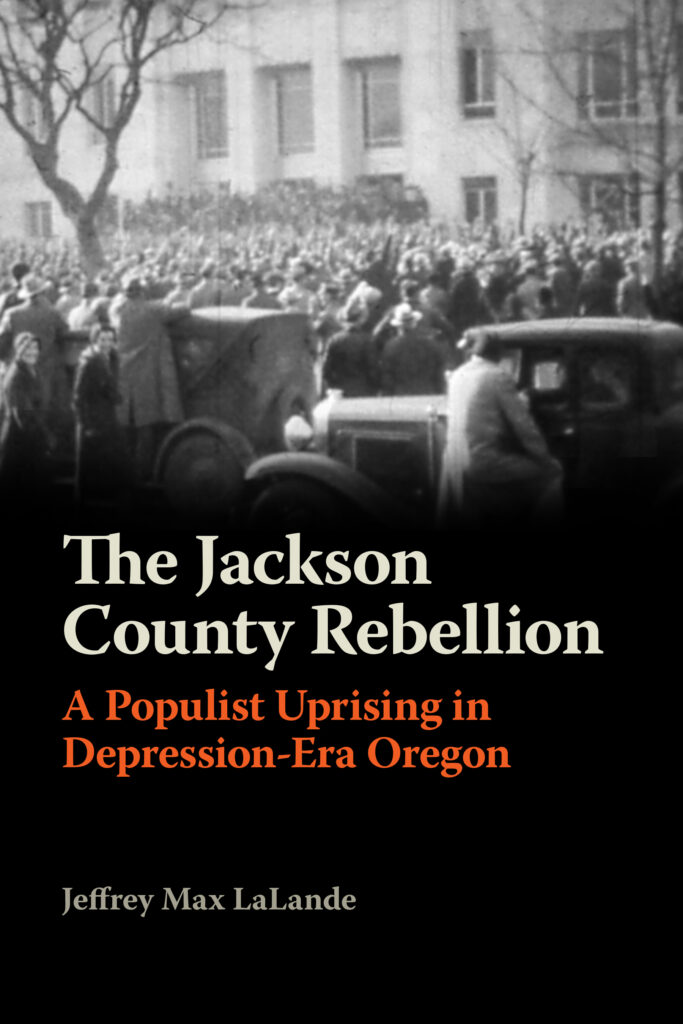

A 1969 graduate of Georgetown University, LaLande earned a master’s degree in archaeology from Oregon State University and a Ph.D. in history from the University of Oregon. He is the author of several books and articles on the history of our region. His most recent book is The Jackson County Rebellion: A Populist Uprising in Depression-Era Oregon, published by Oregon State University Press in 2023.

The Jackson County Rebellion will be available from bookstores in early April or can be ordered directly from the OSU Press.

Battistella: I enjoyed reading The Jackson County Rebellion, and I appreciated the background you gave in the beginning about the populism of the 1890s and early twentieth century. What were some of the factors in the politics of the era?

Jeff LaLande: That second chapter, “Southern Oregon, A Place Apart,” sets the stage for the book’s narrative that follows. It points out the distinctively “different” character of our own part of the state compared to other areas of Oregon – a difference that dates from the earliest days of White settlement and continued on into the twentieth century. Among the factors in this difference were this region’s geographical isolation (mountainous, no navigable rivers, no decent seaports), as well as its settlement during the 1850s-1860s largely by people from the Border States who had Southern sympathies (e.g., White supremacy) and an aversion to Black people, enslaved or free.

There were other reasons as well (discussed in the book). Just one example of this political distinctiveness: in the crucial election of 1860 (the results of which led to the Civil War), Oregon voters gave victory to Republican Abraham Lincoln, while Southern Oregon (i.e., the southwestern part of the state) gave a majority of its votes to the pro-slavery Democratic candidate John Breckenridge. During the nation’s agrarian “Populist Revolt” of the 1890s, our corner of the state was a hotbed of People’s Party. The votes of our angry farmers were in stark contrast to most of the rest of Oregon.

One interesting twist: During the 1905-1912 orchard boom, affluent newcomers (many of them graduates of Ivy League colleges) came to Jackson County as orchardists and professionals. It was a distinctive social stratum unlike that of any other place in the state, outside of Portland.

EB: Do you see some of those same populist-type factors in today’s Jackson County politics?

JL: I do, at least to some extent. There is a continuing strain of very strong political discontent and resentment here. Of course, most politics is (and always has been) rooted in those same tendencies. But our county commissioners are well-practiced in “running against” the urban/liberal electorate of Portland and condemning many of the laws that come out of Salem.

EB: The two main characters in the story of the rebellion were Llewellyn Banks and Earl Fehl, demagogues whose newspapers vilified the Medford establishment, espoused a form of Christian nationalism and advocated a “New Order.” Who were these guys?

JL: Earl Fehl was a Medford building contractor (e.g., the Holly Theater and a number of homes) who’d come to the Valley soon after World War One. A perennial (and perennially unsuccessful) candidate for mayor throughout the Twenties, he also published a weekly newspaper, the Pacific Record Herald, that for years relentlessly castigated Medford’s “establishment” — prominent politicos, attorneys, owner/editor Robert Ruhl of the Medford Mail Tribune, and other such figures (in other words the county’s “elite”) as a corrupt and conspiratorial “Gang” (his term) that plotted against the rights of the common people.

JL: Earl Fehl was a Medford building contractor (e.g., the Holly Theater and a number of homes) who’d come to the Valley soon after World War One. A perennial (and perennially unsuccessful) candidate for mayor throughout the Twenties, he also published a weekly newspaper, the Pacific Record Herald, that for years relentlessly castigated Medford’s “establishment” — prominent politicos, attorneys, owner/editor Robert Ruhl of the Medford Mail Tribune, and other such figures (in other words the county’s “elite”) as a corrupt and conspiratorial “Gang” (his term) that plotted against the rights of the common people.

Llewellyn Banks is a fascinating character. He had been a wealthy citrus orchardist in southern California who, after visiting the Valley, decided to move here in 1926. He held large tracts of pear-orchard land and challenged the existing power structure here of fruit marketing (i.e., on consignment). By confronting the existing, allegedly unfair order of things, Banks earned the admiration of many of the Valley’s smaller fruit growers. He also started his own daily newspaper, the Medford Daily News, in which he called for a dictator (he proposed that senator Huey Long should take on that role) to lead America out of the Depression. Banks steadily turned the News into a virulently “anti-elite” (and, with some regularity, antisemitic) voice, in marked contrast to the moderate editorial tone of the Tribune. Banks believed in himself as a great leader and “man of destiny.” (I’m not a psychologist but I believe Banks likely suffered from an intense megalomania and a malignant form of narcissism.)

EB: What was their Good Government Congress?

JL: When the Great Depression brought hard times to so many people living here, from orchardists to residents of the more remote parts of the Jackson County, Banks and Fehl joined forces – both with their newspapers and with their own local political movement, which they named the “Good Government Congress.” The movement that became the GGC has several thousand active members as well as many other supporters, especially in Medford’s working-class neighborhoods, the Valley’s orchard districts, and in backcountry communities like Butte Falls and Wimer. The aim of the GGC was, whether by legal means (voting) or illegal means (ballot theft) to overturn the alleged “Gang Rule,” and give the reins of government over to the “common people (but actually to Banks and Fehl, who were then drowning in foreclosures from unpaid debts and libel suits). Today, I think we Americans have a difficult time of realizing just how traumatic and frightening the Depression was for so very many people.

EB: Things came to a crisis in the early 1930s with a botched burglary to steal ballots and with Llewellyn Banks later killing a police officer who came to arrest him. What was the aftermath for Banks and Fehl and for Southern Oregon? How did the rest of the state see the Rogue Valley?

JL: The rest of Oregon read with growing interest, in papers such as the Oregonian (which sent a special correspondent down to Medford to cover the story) about the increasing turmoil and threat of violence in Jackson County. The climax came with Banks’s fatal shooting of officer George Prescott, a crime for which he spent the rest of his life behind bars. That story evem made the front page of the New York Herald Tribune.

EB: Tell us a bit about Robert Ruhl, the Pulitzer-winning publisher of the Medford Mail Tribune.

JL: Robert Ruhl came from a well-off family that lived in the affluent Oak Park suburb of Chicago. He went to the exclusive Phillips Andover prep school in Massachusetts, and then on to Harvard (where he worked on the college newspaper with schoolmate Franklin Roosevelt). He came to Jackson County as a young newspaperman in about 1910 as the Valley’s phenomenal orchard boom was winding down.

During the early 1920s he took a notably courageous editorial stand again the local Ku Klux Klan (whose main targets at that time were Roman Catholics and Jews). He did the same thing during the early 1930s — facing boycott and threats of sabotage against his printing press — during the turbulent Jackson County Rebellion (his name for the GGC episode), for which the Trib won a Pulitzer Prize. And in the early 1950s he was one of very few Oregon newspapermen to criticize the demagoguery of Senator Joseph McCarthy.

EB: The print media turned out to be a crucial factor, both in fomenting the rebellion, in exposing it, and in documenting it. I was amazed at the wealth of media you cited from the Medford Mail Tribune, The Daily News, The Pacific Record Herald, and more. As a historian, do you worry that we are losing source of future documentation today?

JL: Yes, definitely. These spreading “news deserts” of today will remain as “history deserts” for future historians and other researchers. (With the sad demise of the Mail Tribune, I’m hopeful that the Rogue Valley Times, Daily Courier, Ashland News, and other such endeavors can succeed where the final owner of the Tribune failed.)

Also, the massive quantities of un-digitized governmental archives are under threat. The Trump Administration wanted the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to remove the Pacific Northwest’s entire massive collection of regional federal archives from Seattle to some place far away. The Jackson County Archives proved crucial to my research, especially the fascinating evidence provided by the district attorney’s investigatory files. The county archives were open to the public at that time, but now they’ve been turned over to management by a private company. I’ve been told that, as a result, the archives are now difficult to access and may even require a fee charged to taxpayers simply to examine some of the material there. Definitely not an improvement!

EB: A writerly question. You originally researched the Jackson County Rebellion for your PhD dissertation. How is the present book publication different? Did you do much rewriting? It read better than the average dissertation and I was pleased to see citations at the end rather than clogging the arteries of the text.

JL: The book is substantially shorter for one thing. I heavily revised (reduced the length of) the first chapters, on the history of the KKK here. In the final chapter, I incorporated substantial new scholarship, studies that came out in the years after my dissertation (e.g., on such things as agricultural marketing, agrarian unrest, and fascism).

EB: The story of the Jackson County Rebellion seems very timely (even eerily prophetic) to me, given recent events in American politics. Do you agree?

JL: I’m glad you asked that question! Most definitely there are a number of parallels between then and now: The profound divide between urban/college-educated (i.e., today’s Blue America) versus the rural and White working-class population (Red America). I think the newspapers of both Banks and Fehl acted much like today’s Fox News and other such right-wing media. Furthermore, they relentlessly accused the Mail Tribune of lying (i.e., charges of “Fake News!”). Many of Banks’s and Fehl’s readers refused to read the Trib, similar to those today who get all their news only from Fox. The GGC’s actual 1933 theft of Jackson County ballots has, I believe, similarities to the goals of the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, and so on.

However, other than a very brief and subtle allusion to our current politics in the book’s preface, I purposely did not raise such parallels and comparisons in the narrative. That wasn’t my job as a historian. Such things are better left to the reader.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

JL: Thanks, Ed. I really enjoyed it.

Follow

Follow

JL: Earl Fehl was a Medford building contractor (e.g., the Holly Theater and a number of homes) who’d come to the Valley soon after World War One. A perennial (and perennially unsuccessful) candidate for mayor throughout the Twenties, he also published a weekly newspaper, the Pacific Record Herald, that for years relentlessly castigated Medford’s “establishment” — prominent politicos, attorneys, owner/editor Robert Ruhl of the Medford Mail Tribune, and other such figures (in other words the county’s “elite”) as a corrupt and conspiratorial “Gang” (his term) that plotted against the rights of the common people.

JL: Earl Fehl was a Medford building contractor (e.g., the Holly Theater and a number of homes) who’d come to the Valley soon after World War One. A perennial (and perennially unsuccessful) candidate for mayor throughout the Twenties, he also published a weekly newspaper, the Pacific Record Herald, that for years relentlessly castigated Medford’s “establishment” — prominent politicos, attorneys, owner/editor Robert Ruhl of the Medford Mail Tribune, and other such figures (in other words the county’s “elite”) as a corrupt and conspiratorial “Gang” (his term) that plotted against the rights of the common people.

DM: I offer everything described above – narration (or casting a narrator), editing, proofing, mastering, and uploading the files. I also offer extra tools for authors who want to narrate their own works, such as a memoir or personal-brand business or life-coach approach to a common problem. I have recording equipment I loan out as needed or offer suggestions on what they need to buy. I offer live direction of the author-narrator during recording to ensure consistency and engagement/energy levels, and to proof the text as they record. I then perform the production steps for the finished audio.

DM: I offer everything described above – narration (or casting a narrator), editing, proofing, mastering, and uploading the files. I also offer extra tools for authors who want to narrate their own works, such as a memoir or personal-brand business or life-coach approach to a common problem. I have recording equipment I loan out as needed or offer suggestions on what they need to buy. I offer live direction of the author-narrator during recording to ensure consistency and engagement/energy levels, and to proof the text as they record. I then perform the production steps for the finished audio. When I first started teaching, one of the books that grounded me in the history of my field was Frederick J. Newmeyer’s Linguistic Theory in America: the first Quarter-Century of Generative Linguistics (Academic Press, 1980). In his new history, American Linguistics in Transition: From Post-Bloomfieldian Structuralism to Generative Grammar, (Oxford UP, 2022), he revisits some of the issues from his earlier work and extends his history of linguistic back to the period of the founding of the Linguistic Society of America in 1924 and forward through the 1980s.

When I first started teaching, one of the books that grounded me in the history of my field was Frederick J. Newmeyer’s Linguistic Theory in America: the first Quarter-Century of Generative Linguistics (Academic Press, 1980). In his new history, American Linguistics in Transition: From Post-Bloomfieldian Structuralism to Generative Grammar, (Oxford UP, 2022), he revisits some of the issues from his earlier work and extends his history of linguistic back to the period of the founding of the Linguistic Society of America in 1924 and forward through the 1980s.