Ceil Lucas is professor emerita of Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C., where she taught linguistics through American Sign Language for 31 years before retiring in 2013. She began teaching Italian at all levels in 1973 and continues to do so. She has edited or co-authored 22 books and also is editor of the scholarly journal, Sign Language Studies, published by Gallaudet University Press.

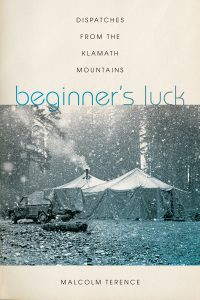

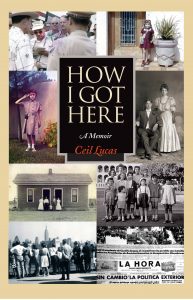

Lucas was born in the United States, but raised from ages 5 to 21 in Guatemala City and in Rome, Italy, and has written a book titled How I Got Here: A Memoir.

Ed Battistella: How I Got Here is an unusual memoir in that covers the early part of your life—up to about the early 1970s. What prompted you to organize the memoir that way?

Ceil Lucas: I always knew that I wanted to write a memoir about my upbringing in Guatemala City and Rome, Italy, 1956 – 1972. Before I started working on the memoir, I had already started working on my family’s genealogy, and I quickly realized that this information would have to be included in the memoir; it was not enough to tell the immediate stories of my parents. I needed to go back as far as I could. In the process, the stories of my ancestors really became my stories and I couldn’t leave them out. At this point, I feel like I know these people. So the memoir is about the 1951 – 1972 period and also about those who came before. It is about how I got here, in the broadest sense.

EB: What’s the significance of the title?

CL: When I came back to go to Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington in August of 1969, I heard myself saying, “Well, I wasn’t raised here; I’m not from here.”, “here” meaning America, the US. But I was starting to plan the memoir at the same time as I was working on my family history and came to find out that my mother’s people came to the Eastern Shore of Maryland from Scotland in 1654, and my father’s people came from England to Philadelphia in 1679. I had to come to terms with the fact that, when your folks arrive in 1654 and 1679, you’re “from here”. So it’s not just about how I came to be born in Phoenix in 1951 or how I got to the US in August of 1969 but how my people got here 122 years before there was an America. The memoir is about the balance between “I’m not from here.” and “I’m deeply American.”

EB: How did your upbringing in Guatemala and Rome affect your perceptions of US events and your sense of yourself as an American?

CL: See above. The effect was more powerful in Rome because I was in Italy during the Vietnam War and got the Italian/European perspective on it, for example, and on US politics in general. But in 1957, my civil engineer father was called to serve as a pallbearer at the funeral of the assassinated Guatemalan president [photo of my father with the casket in the book], in a situation that had totally been engineered by Eisenhower and the brothers Dulles. I was way too young in 1957, of course, to know what was going on, and my father passed before I was able to ask him all the questions I had. But when I went back and studied the history of Guatemala in those days, I was stunned. He was a civil engineer who did civil engineering in Guatemala, worked on irrigation projects, and he was also a fluent Spanish speaker, having been born and raised in New Mexico [he was born in 1909, before it became a state in 1912], but his company was a subcontract to the Dept of State run by John Foster Dulles [of the airport] and Dulles’ brother Allan ran the CIA. I came to find out that they were pretty much the puppeteers. I was ages 5 – 9, having a magical childhood in Guatemala. When I came back for college in 1969, I did NOT have a sense of myself as an American, not at all. I was “other”; Latin American, Italian, European. At 67, that sense of “I’m not from here” lingers, even after 46 years of living and working in the US. I started teaching Italian when I was a grad student, age 22, and am still teaching, not willing to give it up.

CL: See above. The effect was more powerful in Rome because I was in Italy during the Vietnam War and got the Italian/European perspective on it, for example, and on US politics in general. But in 1957, my civil engineer father was called to serve as a pallbearer at the funeral of the assassinated Guatemalan president [photo of my father with the casket in the book], in a situation that had totally been engineered by Eisenhower and the brothers Dulles. I was way too young in 1957, of course, to know what was going on, and my father passed before I was able to ask him all the questions I had. But when I went back and studied the history of Guatemala in those days, I was stunned. He was a civil engineer who did civil engineering in Guatemala, worked on irrigation projects, and he was also a fluent Spanish speaker, having been born and raised in New Mexico [he was born in 1909, before it became a state in 1912], but his company was a subcontract to the Dept of State run by John Foster Dulles [of the airport] and Dulles’ brother Allan ran the CIA. I came to find out that they were pretty much the puppeteers. I was ages 5 – 9, having a magical childhood in Guatemala. When I came back for college in 1969, I did NOT have a sense of myself as an American, not at all. I was “other”; Latin American, Italian, European. At 67, that sense of “I’m not from here” lingers, even after 46 years of living and working in the US. I started teaching Italian when I was a grad student, age 22, and am still teaching, not willing to give it up.

EB: When did your travel experiences awaken an interest in linguistics?

CL: Almost immediately; a chapter in the memoir is called Teaching the Dolls, about how I started teaching my dolls English and Spanish in first grade; I learned to read in Spanish and English at the same time and spoke 4 languages fluently – English, Spanish, French, Italian – by the time I was 10. The interest in language was there from my earliest memories. Good thing ‘cause I can’t do math.

EB: There is a good deal of family history in the book—going back to—what sort of research was involved in that?

CL: A lot of archival research. My mother left a good framework and I picked it up. I got comfortable with the National Archives in Washington, DC, the state archives in Maryland, and several historical societies- Eastern Shore of Maryland, Oklahoma Historical Society, New Mexico Historical Society, the Hackensack, NJ Historical Society, I spent many hours at the National Archives, filling in the framework that my mother left and I became an Ancestry.com member (still am a member) and got a lot of information on line.

EB: What was the writing process like for you compared to, for example, academic writing?

CL: It was a lot more relaxed. A lot of the stories were already formed in my head and just came out very smoothly. I am an academic of 45 years, so the first version of the memoir had references and footnotes in the text itself. I had the great fortune to start an autobiographical writing course the fall after I retired, in 2013, and the genius teacher Susan Moger (herself a novelist) said, “Um, no. Have a references section at the back; in the text makes it dry as toast.” I was so lucky to have her help me shape it. That reference section let me follow my very strong academic instinct to recognize the work of others – I can’t claim to know the history of Oliver Cromwell, for example, the dude who got my folks to Maryland’s Eastern Shore; I needed to research that and many other things – but a memoir is not an academic paper and I had to learn that. It was entirely liberating and I’m still taking the course, long after the memoir has been published. It’s really fun to write what I want without the academic constraints.

EB: How long did the memoir process take, and what was the most difficult aspect of the work?

CL: I had been listing the memories that I wanted to write about for about 3 years and eventually came up with an outline; I knew that I wanted to start with the funeral in Guatemala and go from there. I had written some of the pieces in other creative writing courses but in the fall of 2013, I got organized and made a schedule that had me finishing each section within 2 weeks. By early 2015, it was done.

EB: I was impressed with the many historical images in the book. How did you come by those?

CL: Many of them are family photos and documents that my mother had collected and passed to me and I am so grateful. I think the oldest one I have ( not in the book) is of my great-grandmother as a young woman, taken probably in 1885 and there are a number of vintage ones like that in the book; some images came from the historical societies, from newspapers of the time. A classmate in Guatemala who now runs the school that we went to ( his mother started it ) worked with the National Archives in Guatemala City to find the photo of my father at the funeral (p. 6). The census images, like the one on page 64 and the map on p. 51, are openly available; your tax dollars and mine at work. Others, like the image of Eastern Maryland on p. 69, came with permission from a relative who also worked on our family history. I was extremely careful to secure permission for any image that did not belong to me and people were always quite willing to grant it.

EB: Any advice for other aspiring memoirists?

CL: Do the research and include your family history in your memoir. The stories of all of those people are YOUR stories and helped shape who you are.

EB: Are you planning a sequel covering later times?

CL: I don’t think so. The sheer assembly of the images for my first 18 years plus the archival ones took a lot of work. I don’t think I have it in me to tackle the age 18 – age 67 time period…..

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

CL: Thank YOU for inviting me and for your great questions. It has been a pleasure to share all of this.

Visit the How I Got Here website.

Follow

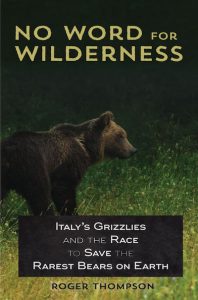

Follow Roger Thompson is an award-winning nonfiction writer, whose work has appeared in both academic and non-academic journals. He is co-author of Beyond Duty: Life on the Frontline of Iraq, a bestselling Iraq War memoir, and has directed an international environmental research program in Banff, Alberta. He taught at the Virginia Military Academy for fourteen years as a Professor of English and fine arts. Thompson currently serves as Director of the Program in Writing and Rhetoric at Stony Brook University. His most recent book is

Roger Thompson is an award-winning nonfiction writer, whose work has appeared in both academic and non-academic journals. He is co-author of Beyond Duty: Life on the Frontline of Iraq, a bestselling Iraq War memoir, and has directed an international environmental research program in Banff, Alberta. He taught at the Virginia Military Academy for fourteen years as a Professor of English and fine arts. Thompson currently serves as Director of the Program in Writing and Rhetoric at Stony Brook University. His most recent book is  RT: Bruno was born of a Slovenian sow and was among the first cubs born of an ambitious rewilding program in the north of Italy. Slovenian brown bears are not entirely unlike the American grizzly, and while the rewilding program that introduced them into the Italian Alps was by many measures a tremendous success, local Italians began to have conflict with the bears. The question began to be reasonably asked whether an introduced bear is as well suited to a region as a native population. The Abruzzo bears, unlike Bruno and his Slovenian ancestors, are entirely native to Italy. They have lived in the Apennines for a millenia, have adapted to that habitat, and are notoriously peaceful. While in the Alps, there have been a few problematic human-bear interactions, in Abruzzo, the bears have never in written record attacked a human. That’s a thousand years of recorded history without a single attack of a a bear on a human. They are an astonishing species of bear.

RT: Bruno was born of a Slovenian sow and was among the first cubs born of an ambitious rewilding program in the north of Italy. Slovenian brown bears are not entirely unlike the American grizzly, and while the rewilding program that introduced them into the Italian Alps was by many measures a tremendous success, local Italians began to have conflict with the bears. The question began to be reasonably asked whether an introduced bear is as well suited to a region as a native population. The Abruzzo bears, unlike Bruno and his Slovenian ancestors, are entirely native to Italy. They have lived in the Apennines for a millenia, have adapted to that habitat, and are notoriously peaceful. While in the Alps, there have been a few problematic human-bear interactions, in Abruzzo, the bears have never in written record attacked a human. That’s a thousand years of recorded history without a single attack of a a bear on a human. They are an astonishing species of bear.

Malcolm Terence left his job as a reporter at the Los Angeles Times in the late 1960s and helped found a large hippie commune in the Klamath Mountains. He followed that with logging and reforestation work, setting up–and opposing–timber sales, and fighting wildfires.

Malcolm Terence left his job as a reporter at the Los Angeles Times in the late 1960s and helped found a large hippie commune in the Klamath Mountains. He followed that with logging and reforestation work, setting up–and opposing–timber sales, and fighting wildfires.