Malcolm Terence left his job as a reporter at the Los Angeles Times in the late 1960s and helped found a large hippie commune in the Klamath Mountains. He followed that with logging and reforestation work, setting up–and opposing–timber sales, and fighting wildfires.

Malcolm Terence left his job as a reporter at the Los Angeles Times in the late 1960s and helped found a large hippie commune in the Klamath Mountains. He followed that with logging and reforestation work, setting up–and opposing–timber sales, and fighting wildfires.

Along the way, he married a local schoolteacher and raised a family. He still writes for regional papers, teaches, and cultivates a large garden.

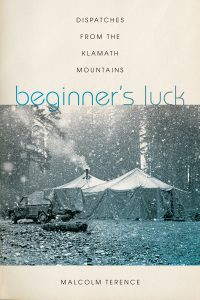

Beginner’s Luck is his first book.

Malcolm Terence will be reading and signing books at Bloomsbury Books in Ashland, June 18th, 2018 at 7 pm. It’s free and open to the public.

Ed Battistella: How did you find your way to the Black Bear Ranch in the 1960s? Tell us a little about your background and journey.

MT: When I came to Siskiyou County in 1968, it was not a friendly place to hippies. I’d left the Los Angeles Times where I’d been a reporter and then as business manager for a band of gifted musicians. I traveled with them to shows and recording dates on both coasts, but drifted away when I met the Diggers, a radical theatrical gang in San Francisco. I confess I thought them a little crazy, but when a few of them wanted to start a new commune in the mountains, I jumped in. That year, 1968, was like that. It was a full day’s drive from San Francisco and the last many miles were just the sketchiest of roads. I arrived midday and maybe 20 minutes later two carloads of deputies came in and arrested me. It seems like yesterday, but 1968 was a half century ago.

EB: Tell us a bit about your book Beginners’ Luck, where you tell the stories of commune and the nearby towns.

MT: When I moved to the mountains I figured that news was something that came out of the city halls, the courthouses and the police stations that I’d worked in Los Angeles, so I stopped writing. Instead I learned about goats, firewood and the reality of living with sixty hippies in the middle of nowhere. There was no internet then and not even many telephones, certainly none at Black Bear. But over the years it became apparent that the stories unfolding around me were as important and as gripping as those that had been on my beat in Los Angeles.

EB: What’s the significance of the title?

MT: Specifically it’s from a time when a Native American friend took me to play cards with his friends near the ceremonial grounds. But more broadly, I came in clueless but got by. I got by with the help of the few locals who found us hapless hippies kind of interesting. That’s been my luck all along. I’m grateful.

EB: How did the community sustain itself over the years?

MT: The folks at the commune gardened, of course, but that was seasonal. Some people qualified for welfare payments, what they call TANF nowadays, and shared them. A few people came from wealthy families and their parents might send them occasional checks. We called that stay-away-from-home money. Since we were snowed in every winter in those days, we’d send out a big truck in the fall once or twice to get the winter’s provisions. Huge amounts of un-milled wheat and potatoes, barrels of oil, big sacks of beans. The Diggers still in the City helped with that.

EB: You’ve also been involved with reforestation work. How did that come about?

MT: Some of the commune expates moved to the river towns and started doing jobs planting small trees in the clear cuts where logging had just happened. People liked it because it was seasonal, which left them time for their homesteads the rest of the year. After one season they organized it as an employee-owned co-op.

EB: You were one of the people who stuck it out. How did the community evolve over time? What changes did you see?

MT: I lasted four years at the commune and left when I felt I’d had enough. I tried San Francisco again for a while and also Santa Cruz, but then I returned to the river. I’d had enough of commune life but the little towns along the river, the mix of Native Americans, rednecks, agency people and other hippies had figured out how to get along. They might have doubts about each other, they might harbor reservations, but they made it work, especially when everybody was needed for things like firefighting or opposing the Forest Service policy of herbicide use in the forest.

EB: Do you think that some of these environmental collaborations served as the basis for later cooperative efforts with watershed projects?

MT: It lay the foundations for work later by restoration non-profits and for productive collaboration with the neighboring tribes. Even the Forest Service has signed on. I call that a miracle, given where we started, and salute all our brilliant allies. I’ve been especially impressed by the caliber of our children, both the ones who returned to urban settings and the ones who stayed or who went to college and then came back. They are so much smarter and so much more politically astute than their parent’s generation, my generation. They work with the Tribe, with the Forest Service, with environmental groups and with a couple of powerful restoration non-profits. Early on we elders saw the benefits of getting along with the non-hippie neighbors, but our kids are really good at it. I’m proud of them and awed.

EB:Are there similarities between America today and our country 50 years ago when the commune started?

MT: Some things seem different. People smoke pot openly and men have beards and long hair, but those shifts are kind of superficial. On a deeper level, the country is still drastically divided in culture and politics. There is a crazy war that goes on and on without clear benefits. There are still deep divisions over issues of gender, class, race and much more. There is more poverty and more concentration of great wealth. The government talks democracy, but practices secrecy, corruption and authoritarianism. Is Trump worse than Nixon? We may have been utopians, but we didn’t leave a very perfect world for our kids. Still, if we hadn’t done the work we did, culturally and politically, it would be even worse. I remain an optimist.

EB: Thanks for talking with us. Good luck with your book.

MT: I hope you find it interesting.

Follow

Follow