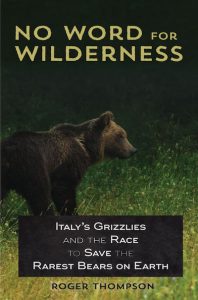

Roger Thompson is an award-winning nonfiction writer, whose work has appeared in both academic and non-academic journals. He is co-author of Beyond Duty: Life on the Frontline of Iraq, a bestselling Iraq War memoir, and has directed an international environmental research program in Banff, Alberta. He taught at the Virginia Military Academy for fourteen years as a Professor of English and fine arts. Thompson currently serves as Director of the Program in Writing and Rhetoric at Stony Brook University. His most recent book is No Word for Wilderness published by Ashland Creek Press.

Roger Thompson is an award-winning nonfiction writer, whose work has appeared in both academic and non-academic journals. He is co-author of Beyond Duty: Life on the Frontline of Iraq, a bestselling Iraq War memoir, and has directed an international environmental research program in Banff, Alberta. He taught at the Virginia Military Academy for fourteen years as a Professor of English and fine arts. Thompson currently serves as Director of the Program in Writing and Rhetoric at Stony Brook University. His most recent book is No Word for Wilderness published by Ashland Creek Press.

Ed Battistella: Congratulations on No Word for Wilderness. Tell us a little about your book and about the Abruzzi bears living not far from Rome.

Roger Thompson: Thanks Ed. The book details the surprising lives and current threats to a group of brown bears only 50 miles from Rome. Few people seem to know about these bears, and when I first learned about them myself, I was captivated by their story. Only 50 of the bears now remain, and they are facing surprising threats to their survival.

EB: As a linguist, I was fascinated by the title observation, that there is No Word for Wilderness in Italian. What does that tell us?

RT: It’s not entirely unusual for a language not to have a word for the idea of “wilderness,” but in Italy, I think it’s especially important because it points to some of the challenges for wildlife in the country. When a country has no meaningful word to describe wild places, it is especially difficult to convince a population to rally for conservation. It’s hard to save what you can’t name.

EB: A lot of the book is devoted to the aptly named Bruno. What is Bruno’s story?

RT: Bruno is bear from northern Italy who, in 2006, became probably the most famous bear the world has ever known. He migrated from Italy to Germany just as Germany began to welcome soccer fans for the World Cup, and the result was massive media coverage of Bruno’s exploits. Bruno had a habit of killing domestic animals, and while there is lingering disagreement over the degree of danger Bruno posed, the German government certainly decided that he would not be tolerated. So, what began as a story about the first wild bear in Germany in over 150 years became the story of how a government responded to a wildlife crisis–a crisis some believe the country itself created.

EB: How are the Abruzzi bears different?

RT: Bruno was born of a Slovenian sow and was among the first cubs born of an ambitious rewilding program in the north of Italy. Slovenian brown bears are not entirely unlike the American grizzly, and while the rewilding program that introduced them into the Italian Alps was by many measures a tremendous success, local Italians began to have conflict with the bears. The question began to be reasonably asked whether an introduced bear is as well suited to a region as a native population. The Abruzzo bears, unlike Bruno and his Slovenian ancestors, are entirely native to Italy. They have lived in the Apennines for a millenia, have adapted to that habitat, and are notoriously peaceful. While in the Alps, there have been a few problematic human-bear interactions, in Abruzzo, the bears have never in written record attacked a human. That’s a thousand years of recorded history without a single attack of a a bear on a human. They are an astonishing species of bear.

RT: Bruno was born of a Slovenian sow and was among the first cubs born of an ambitious rewilding program in the north of Italy. Slovenian brown bears are not entirely unlike the American grizzly, and while the rewilding program that introduced them into the Italian Alps was by many measures a tremendous success, local Italians began to have conflict with the bears. The question began to be reasonably asked whether an introduced bear is as well suited to a region as a native population. The Abruzzo bears, unlike Bruno and his Slovenian ancestors, are entirely native to Italy. They have lived in the Apennines for a millenia, have adapted to that habitat, and are notoriously peaceful. While in the Alps, there have been a few problematic human-bear interactions, in Abruzzo, the bears have never in written record attacked a human. That’s a thousand years of recorded history without a single attack of a a bear on a human. They are an astonishing species of bear.

EB: What is the state of the national parks system in Italy? I had never given it much thought before reading your book.

RT: National Parks issues in Italy are complicated. On the one hand, the country can boast an rapid expansion of the national park system over the last 50 to 100 years, faster than any other country in such a short period of time. On the other hand, the management of the land is a complex mix of national, regional, and local politics. Park Presidents are appointed as political favors, and it’s not unusual to have president appointees who have very little investment in parkland. A park granted to a president may be something akin to a bauble to brag about for an individual. Certainly, some park presidents are impressive people, and the current park president of Abruzzo National Park, which is home to most of the Abruzzo bears, is generally well regarded. Still, the system is deeply flawed, and as a result, conservation initiatives are hard to carry out over long periods of time.

EB: What does this story tell us about the wilderness—development divide? Or about attitudes toward wildlife and land more generally?

RT: To me, it suggests quite simply that the divide can be bridged. If bears and humans can coexist in Italy, they can in other parts of the world–even highly populated parts. It may require us to rethink the idea of the wild, but it still suggests pretty astonishing possibilities for the wild to not only live, but potentially thrive, alongside thoughtful and intentional development.

EB: How did you come to be a nature writer? And, as a university professor, do you have any advice for aspiring writers?

RT: I don’t have a good answer to the first part of this question. I read a lot of science writing and nonfiction, and my first piece of published nonfiction was nature writing and won an award, so I figured I might have some talent there. Still, I’m a bit hesitant to group myself with the far more accomplished groups of writers who can probably more rightly be called nature writers. As to advice, it’s pretty simple. You have to write. Then, you have to send your writing out for consideration. Then you have to endure repeated rejection with an open mind–meaning, you may need to change things about your writing. And lastly, if someone wants a career in writing–you’ll note I took the easy way out and found a full time job that allows me to write as part of my job description!–but if you want to be a full time writer, I would recommend starting with nonfiction. Fiction is tough to break into. Nonfiction or professional writing–not nearly as hard. Oh, and let me add what one of my mentors once told me: if you write fast and on deadline, work will come to you. I think this is quite true.

EB: As a writer about nature, do you have some favorite authors?

RT: Hard to beat McPhee and Lopez. I’m a sucker for Sigurd Olson. I admit I’m impatient with a lot of the self-reflective wanderings in the wilderness books, but I do find myself drawn to work that is engaged with the world and wants to make a difference. Sometimes I think that a lot of journalists who write books may have a better ear for audiences than people coming out of MFA programs.

EB: How did you happen to choose Ashland Creek Press to publish No Word for Wilderness?

RT: I had some offers on the book that I didn’t feel as confident about. Ashland Creek appealed to me simply because they seem genuinely invested in the project. I’ve published enough to feel a bit selfish. I really do want to find the right press for my work. I don’t mean that in any sort of holier-than-thou artistic way. I don’t feel protective of my words, and I try hard to listen to editors and their advice. I just mean to say that I don’t have to sell a book in order to make a living, so I like the idea of finding a publisher who actually cares about my project. The folks at Ashland Creek very much did, and they were just great editors.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

RT: It was a real pleasure. Thank you.

Follow

Follow