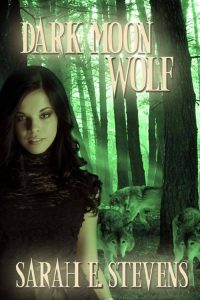

Sarah E. Stevens began her love of writing and fantasy with the tales of Narnia, Middle Earth, and Pern. A fan of all fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction, she started playing Dungeons& Dragons with the good old boxed sets. She still plays today, but divides her time between art, work, family (her partner Gary, their three kids, three cats, some fish and some hermit crabs), and writing. Dark Moon Wolf is her first novel.

Sarah E. Stevens began her love of writing and fantasy with the tales of Narnia, Middle Earth, and Pern. A fan of all fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction, she started playing Dungeons& Dragons with the good old boxed sets. She still plays today, but divides her time between art, work, family (her partner Gary, their three kids, three cats, some fish and some hermit crabs), and writing. Dark Moon Wolf is her first novel.

Sarah E. Stevens lives in Evansville, Indiana. You can learn more at her website sarahestevens.com and Twitter feed @sessiesarah .

EB: Tell us about Dark Moon Wolf.

SS: Dark Moon Wolf is a paranormal novel about Julie Hall, who discovers her four month old baby Carson is a Werewolf. She’s a single mom and a librarian in Jacksonville, kind of an everywoman, and estranged from Carson’s father—who never even knew she was pregnant. In her search for answers, Julie travels to Greybull, Wyoming to find her ex-boyfriend in the hope he has some idea of how Carson could be a Were. She does find answers, but also becomes the target of a mysterious enemy that’s out to kill her—or her son.

In addition to the intrigue of the plot, my novel revolves around motherhood and strong female friendships. Julie’s relationship with Carson is crucial throughout the book. And she couldn’t survive without a tight trio of friendship that springs up between her, her best friend Sheila, and a Werewolf named Eliza.

EB: The story involves a single mom who discovers that her son is a werewolf. How did you come up with that idea. And how did your kids react?

SS: When my son Zack was four months old, he bit my shoulder so hard that I actually have a scar from one of his teeth. He wasn’t being vicious—he was in pain from teething and from acid reflux and he just clamped down as I held him. It HURT. At the time, I remember saying a bunch of swear words and then randomly thinking, “Well, at least he’s not a Werewolf.” Then I thought… wait a minute, what if he WERE a Werewolf? How would he have become a Werewolf? That would mean everything we think we know about Weres is wrong… And that was the seed of the book. My kids think it is hilarious that Zack’s bite spawned the whole thing. And Zack likes to look at the scar on my shoulder, even though he definitely feels bad that he hurt me.

EB: How did you develop your Werewolves to be so different than the typical Weres?

SS: I love reading fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction, so I’ve read a lot of Werewolf novels. But one thing that’s always rubbed me wrong is that most writers imagine the wolf swallowing the human. Were stories describe communities focused on the alpha male, who’s usually the bad-boy love interest. What if Weres were more human than wolf? Or as much human as wolf? What if pack status didn’t revolve around brute strength, but something else? Those questions were central to my development of the Weres’ relationship to the moon and its powers. I wanted my Weres to be more than just shape-shifters, and to be less patriarchal in structure.

EB: Part of the story is set here in southern Oregon. Is this a particularly good setting for the supernatural?

SS: I think so! Besides, write what you know—isn’t that what they say? The opening of Dark Moon Wolf is set in southern Oregon. Julie’s best friend even teaches at Southern Oregon University. Julie’s adventures then take her to Greybull, Wyoming and Las Vegas—both places I’ve travelled to and know something about.

EB: What the attraction of werewolves, vampires, and so on to readers, in your opinion?

SS: Part of the reason we like fantasy in general, I think, is for the escapism it provides. Who doesn’t want to think they might meet a fairy around the corner or experience real magic in their normal lives? Paranormal fiction merges our everyday lives and fantastical elements, so we can inject ourselves into that built world in a different way than is possible in high fantasy. I think that meld of reality and fantasy is a major part of the allure. At the same time, all fantasy genres just provide a different canvas on which to explore the same central life questions that all literature explores.

SS: Part of the reason we like fantasy in general, I think, is for the escapism it provides. Who doesn’t want to think they might meet a fairy around the corner or experience real magic in their normal lives? Paranormal fiction merges our everyday lives and fantastical elements, so we can inject ourselves into that built world in a different way than is possible in high fantasy. I think that meld of reality and fantasy is a major part of the allure. At the same time, all fantasy genres just provide a different canvas on which to explore the same central life questions that all literature explores.

EB: Dark Moon Wolf is part of a planned series. What’s next?

SS: The second book in the series, Waxing Moon, is also under contract and in the editing process. The entirety of Waxing Moon is set in southern Oregon, and I had a lot of fun describing the area and bringing in locations like Lithia Park. In Waxing Moon, Julie and her son are under attack from a group Salamanders, a paranormal species with powers of light and fire. Salamanders and Werewolves exist in a kind of yin-yang relationship, balancing the sun and the moon. I enjoyed coming up with what is—to my knowledge—a new paranormal race. Waxing Moon also brings in a couple of love interests for Julie.

EB: You are a self-described “board-game geek.” What are some of your favorites?

SS: Such a hard question! Everyone in my family of five is a board game geek. When I talk about board games, I mean modern niche/hobby board games, not things like Monopoly or Risk (which are fine games, just not what I mean!). I prefer Euro-style strategy games like Terra Mystica, Euphoria, and Viticulture. Lighter games—Mysterium, Carcassonne—and party games such as One Night Ultimate Werewolf also get a lot of play at our house. Our family has a standing Thursday night Dungeons & Dragons campaign and we also play Magic the Gathering, a collectible card game. Overall geeks.

EB: Who are some of your favorite authors?

SS: Everyone who loves fantasy is going to start with J.R.R. Tolkien, for good reason. I grew up also reading C.S. Lewis, Madeline L’Engle, Anne McCaffrey, Ursula LeGuin, and Octavia Butler. Right now, two of my favorites are Robin Hobb and Sharon Shinn. I met Robin Hobb at GenCon this past summer and went totally fangirl on her. I love her skills at world-building and the way she develops characters.

EB: You’ve also got a day job. Tell us a bit about your writing life.

SS: I don’t find nearly enough time to write. I work full-time, teach a university class on top of that, and have three kids. I’m working on book three of my series right now, tentatively titled Rising Wolf. I have a separate book living in my head, and hope to have time to start it in the next six months. Sometimes I snatch 30 minutes of writing in the morning before work. Sometimes I write during my lunch time. Sometimes I write for an hour or so in the evenings after the kids are in bed. There are days I don’t write at all, though—too many of those. Thank goodness for things like iCloud, where my most recent manuscript can be pulled up anywhere, anytime. I also have other hobbies that demand some time—gaming, painting, making chain maille jewelry. I try to remember that every word and every page counts!

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

SS: Thanks so much for having me!

Follow

Follow