TOD DAVIES is the author of The History of Arcadia series: Snotty Saves the Day, Lily the Silent, The Lizard Princess and now Report to Megalopolis: or The Post-modern Prometheus, which Kirkus Reviews called “A philosophical fable.”

TOD DAVIES is the author of The History of Arcadia series: Snotty Saves the Day, Lily the Silent, The Lizard Princess and now Report to Megalopolis: or The Post-modern Prometheus, which Kirkus Reviews called “A philosophical fable.”

Tod is also the author two cooking memoirs Jam Today: A Diary of Cooking With What You’ve Got and Jam Today Too: The Revolution Will Not Be Catered.

Along with that, she’s the editorial director of Exterminating Angel Press and EAP: The Magazine. Tod lives with her husband, the filmmaker Alex Cox, and their two dogs in Colestin, Oregon.

Ed Battistella: You have recently released the audiobook version of Snotty Saves the Day produced by Last Word Audio and read by Colby Elliott. What motivated you to release Snotty as an audiobook?

Tod Davies: I’ve been wanting to get more into audiobooks in a big way, since I think they are one of the fastest growing platforms for books. But I especially wanted to do The History of Arcadia series that way—it’s particularly good content for an aural experience, since it’s a bunch of different voices chiming in on how the world can change, and why. The series was conceived as a unified theme told by many different types of literary voice, including the early spoken story of fairy tales, legends, and myths. I knew it would be fascinating to hear, as well as see it on the page.

EB: Do you think more people are listening to audio books, these days? I know I am.

TD: Oh, absolutely. Anecdotally, some of my closest friends are addicted to them. For many good reasons: long commute drives, need to relax while doing other chores, less strain on eyes that have spent all day on the computer, etc. That screen time is an increasing drag. And the fact that the younger generation likes to travel light means they don’t want to pack up books for the next move. Audiobooks fit in perfectly with that ‘don’t want to own a lot of stuff’ ethos.

EB: This is the second EAP book you’ve released as an audiobook. Are you planning to do the whole History of Arcadia series? How about the Jam Today books?

TD: To have the entire The History of Arcadia series as a Last Word Audio production is an author’s dream come true. I think Colby Elliott is a dream narrator (and these books should be read, or heard, as a long dream). But the next two in the series are narrated by women, and I’m not sure Colby wants to take that on. It would be great if Last Word found a great woman narrator for those two.

EB: What makes a good audiobook in your opinion?

TD: A really engaging narrator is the main thing. One of my dearest friends is an avid audiobookphile, and she says she’ll listen to content she wouldn’t usually go for if the narrator is one she loves. She likens it to restaurants: “If the food is great but the service is terrible, you won’t go back. But if the food is only good and the service is wonderful, you WILL go back.” Of course you need good content, since if the food is great and the service is wonderful, it’s a perfect score. I do think you need content that lends itself to person-to-ear narration. Incidentally, I love that we’re coming full circle, and returning to bard recitation of story!

EB: Snotty Save the Day and The Supergirls were read by Colby Elliott of Last Work Audio. How did you discover him?

TD: Actually, he discovered me, or at least, EAP books. He got in touch after reading Mike Madrid’s The Supergirls, and said he wanted to do it as an audiobook. I even think it was one of the first that Last Word Audio did, though of course now they have a huge list. Anyway, we arranged a phone call, and I could tell right away that Colby was my perfect kind of partner. Usually I can tell pretty quickly, which saves a lot of time and angst. And Colby was obviously multi-talented, no-nonsense, and very human, which last is probably the most important. This was particularly lucky, since I’d been dreaming about doing audiobooks, though at the time I had my hands completely full with publishing our list. That’s slowed down now, fourteen books later, and I’m looking to expand our publishing horizons in a different direction. Audiobooks are a big part of that vision.

TD: Actually, he discovered me, or at least, EAP books. He got in touch after reading Mike Madrid’s The Supergirls, and said he wanted to do it as an audiobook. I even think it was one of the first that Last Word Audio did, though of course now they have a huge list. Anyway, we arranged a phone call, and I could tell right away that Colby was my perfect kind of partner. Usually I can tell pretty quickly, which saves a lot of time and angst. And Colby was obviously multi-talented, no-nonsense, and very human, which last is probably the most important. This was particularly lucky, since I’d been dreaming about doing audiobooks, though at the time I had my hands completely full with publishing our list. That’s slowed down now, fourteen books later, and I’m looking to expand our publishing horizons in a different direction. Audiobooks are a big part of that vision.

EB: Have you ever thought of narrating your own books?

TD: I think The History of Arcadia series needs another set of voices than just mine. The more the merrier, as long as they are, literally, on the same page. And you know, I never could have figured out how to handle the footnotes in Snotty Saves the Day, and you’ll hear that Colby did an enchanting job with them. I was thrilled.

I’d love to see Arcadia as a streaming series, and I can tell you, I would not want to be the showrunner on that! It would need another perspective. Other perspectives are always a great thing.

That said, I think I may be the best person to narrate the Jam Today cookbook/memoir series, since in great part it’s about my wistful desire to actually be in the reader’s kitchen, holding my glass of wine, and chatting about what they’re doing for dinner. So an audio narration would get me that much closer. It wouldn’t be tough for the recipes, since all of them in the Jam Today series are so flexible. I could adlib. I’d like that. That’s why you embrace as many platforms as possible—every one is a different way of looking at the material.

EB: Any Exterminating Angel news you can share?

TD: I’m focusing more on writing these days. I do find that all those years of endless multitasking have left me with my multitasking capability worn plumb out. So writing is more than enough for me right now. I’m working on the fifth The History of Arcadia book, narrated by a member of the next generation of Arcadians. She cannot understand why the older generation is so obsessed with defeating Megalopolis when there is so much to enjoy about life. Kali, my heroine, just wants to get on with having fun, and to be left alone to enjoy her hybrid monster companion and friends from over the forbidden border to imperial Pavopolis. She learns what she needs to do in her generation to evolve to something completely new, a solution never thought of before.

I’m also writing My Life with Dogs, which is kind of a memoir about dogs in the same way that the Jam Today books are about food—really it’s just a way to get into talking about my own experience of life in this time and place. It does feature some wonderful dogs, though, I will say that.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

TD: My dear Literary Ashland, always a pleasure. Looking forward already to our next chat.

Follow

Follow Stephanie Raffelock is the author of Creatrix Rising, Unlocking the Power of Midlife Women, (She Writes Press – August, 2021). She also penned the award winning book, A Delightful Little Book on Aging.

Stephanie Raffelock is the author of Creatrix Rising, Unlocking the Power of Midlife Women, (She Writes Press – August, 2021). She also penned the award winning book, A Delightful Little Book on Aging.  SR: Self-knowledge reveals all things. Somewhere along the way, I committed to living the examined life. The older I’ve gotten, the more I’ve been able to appreciate the psychological and spiritual insights not only within my self, but within others as they walk the path of what we call the human experience.

SR: Self-knowledge reveals all things. Somewhere along the way, I committed to living the examined life. The older I’ve gotten, the more I’ve been able to appreciate the psychological and spiritual insights not only within my self, but within others as they walk the path of what we call the human experience. EB: Tell us about your earlier book on aging,

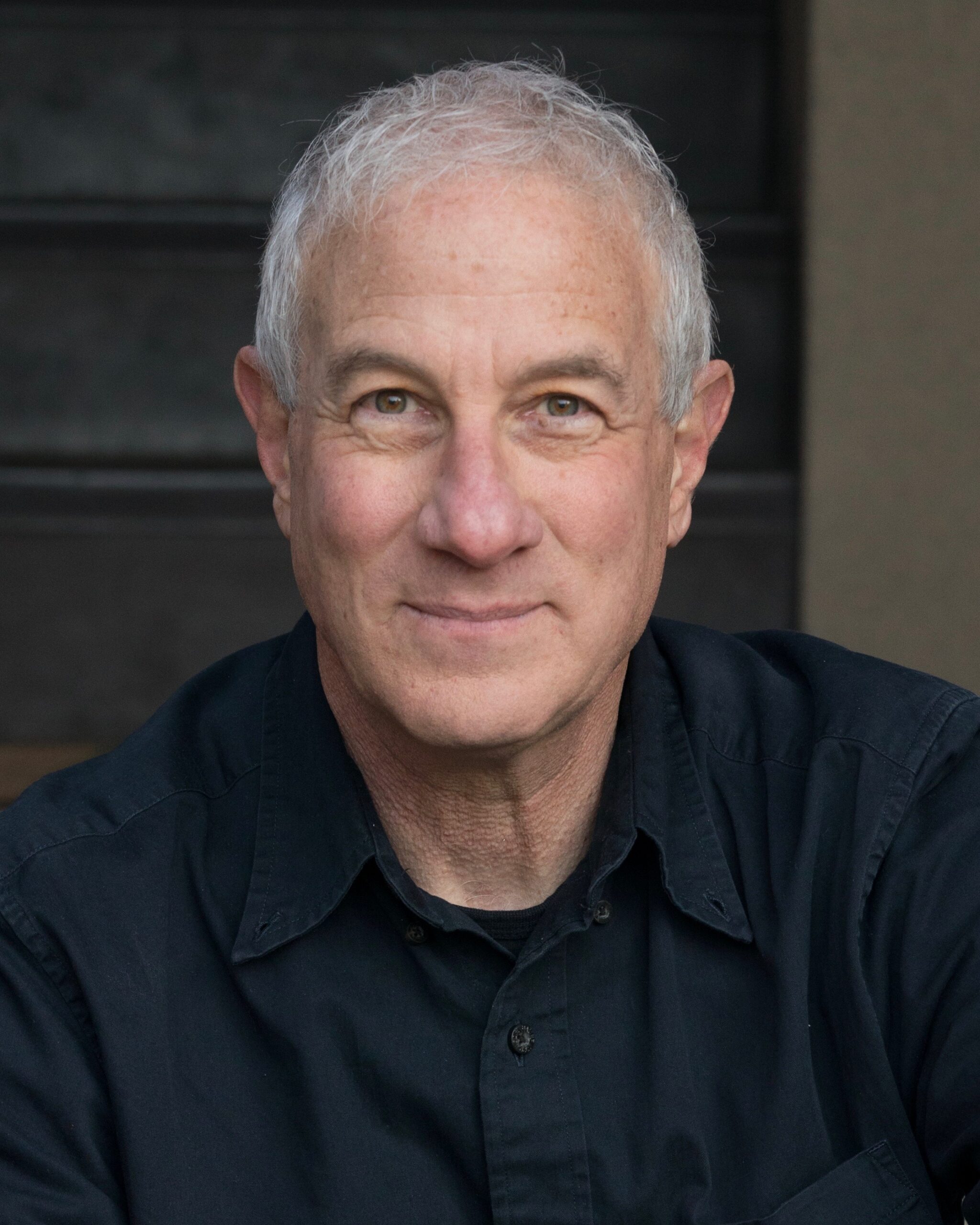

EB: Tell us about your earlier book on aging,  Scott Kaiser is a director, playwright, master teacher of acting, and author who spent 28 seasons as a member of the artistic staff at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland, where he directed, adapted, coached, or performed in all 38 of Shakespeare’s plays.

Scott Kaiser is a director, playwright, master teacher of acting, and author who spent 28 seasons as a member of the artistic staff at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland, where he directed, adapted, coached, or performed in all 38 of Shakespeare’s plays. SK: Like most satires, the aim of the book is not necessarily to advocate for particular changes, but to hold a mirror up to all the absurdity that Shakespeare inspires in our modern culture. Such as endless movie adaptations, “translations” of his work into plain English, people who want to ban him from the curriculum, Anti-Stratfordians who believe in a centuries-old conspiracy, First Folio freaks, original pronunciation geeks, thousands upon thousands of books and dissertations about the Bard’s life and work, bottomless merchandising of every conceivable Shakespeare-related product, and so on, ad nauseam.

SK: Like most satires, the aim of the book is not necessarily to advocate for particular changes, but to hold a mirror up to all the absurdity that Shakespeare inspires in our modern culture. Such as endless movie adaptations, “translations” of his work into plain English, people who want to ban him from the curriculum, Anti-Stratfordians who believe in a centuries-old conspiracy, First Folio freaks, original pronunciation geeks, thousands upon thousands of books and dissertations about the Bard’s life and work, bottomless merchandising of every conceivable Shakespeare-related product, and so on, ad nauseam. Amber R. Reed is the author of

Amber R. Reed is the author of  AR: A clear example from my research is the nostalgia rural Xhosa teachers have for students during the apartheid era. They wax nostalgic for how the apartheid government was strict in schools and helped them manage their classrooms – students were well-behaved, the curricula allowed them to teach in ways they felt aligned with their cultural emphasis on rigid age hierarchies, corporal punishment was legal, etc. By comparison, democracy today in South Africa feels like an imposition; national human rights legislation has made corporal punishment illegal, the curricula demand active learning and student participation, lessons are supposed to include teaching about LGBTQ rights. These are all things many Xhosa people consider foreign and even immoral, and nostalgia becomes a way to recapture a sense of security from the past.

AR: A clear example from my research is the nostalgia rural Xhosa teachers have for students during the apartheid era. They wax nostalgic for how the apartheid government was strict in schools and helped them manage their classrooms – students were well-behaved, the curricula allowed them to teach in ways they felt aligned with their cultural emphasis on rigid age hierarchies, corporal punishment was legal, etc. By comparison, democracy today in South Africa feels like an imposition; national human rights legislation has made corporal punishment illegal, the curricula demand active learning and student participation, lessons are supposed to include teaching about LGBTQ rights. These are all things many Xhosa people consider foreign and even immoral, and nostalgia becomes a way to recapture a sense of security from the past.