photo credit: Ivan Farkas

Margalit Fox is the author of three previous books: Talking Hands: What Sign Language Reveals about the Mind (Simon & Schuster, 2007); The Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient Code (Ecco/HarperCollins, 2013), which received the William Saroyan Prize for International Writing; and Conan Doyle for the Defense: The True Story of a Sensational British Murder, a Quest for Justice, and the World’s Most Famous Detective Writer (Random House, 2018).

Ms. Fox enjoyed a 24-year-career at the New York Times, as an editor at the Sunday Book Review and a senior writer in the Obituary News department. She received the Front Page Award from the Newswomen’s Club of New York in 2011 for feature writing, and in 2015 for beat reporting. She is one of four authors whose work is prominently featured in Steven Pinker’s 2014 best seller, The Sense of Style; in 2016, the Poynter Institute named her one of the six best writers in the Times’s history. With her Times colleagues, she stars in Obit, Vanessa Gould’s acclaimed documentary of 2017.

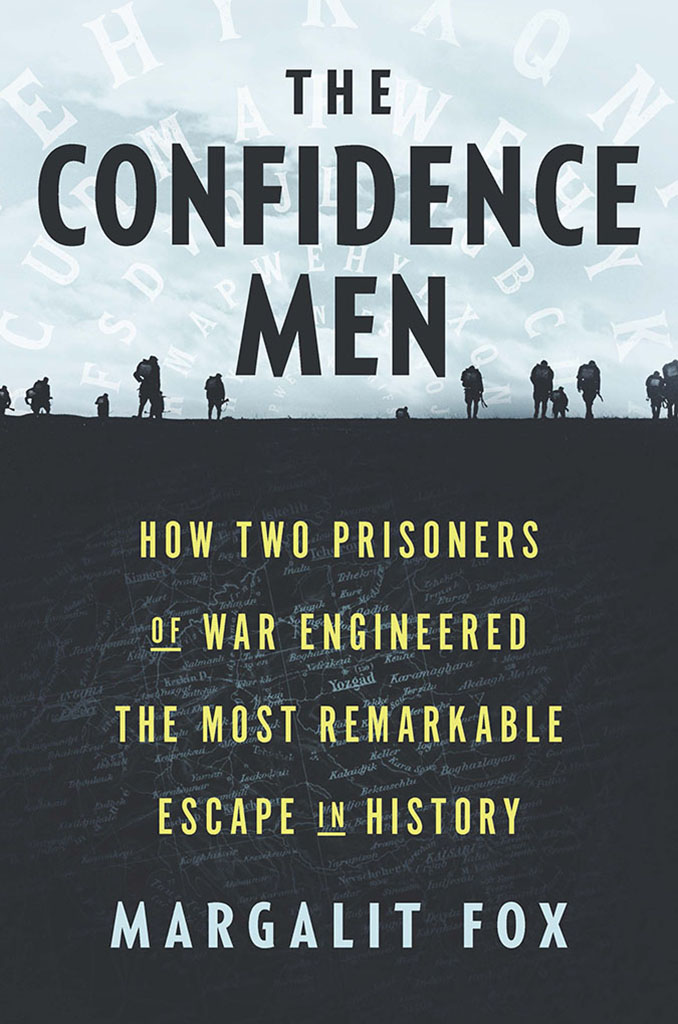

Her recently released nonfiction thriller, The Confidence Men: How Two Prisoners of War Engineered the Most Remarkable Escape in History, published by Random House, tells the true story of Elias Henry Jones and Cedric Waters Hill, two British POWs who orchestrated an elaborate con game, centering on a handmade Ouija board, that let them flee a Turkish prison camp during World War I. Publishers Weekly called The Confidence Men a “marvelous history” and the Washington Post said it was “enthralling.” (@margalitfox; #FoxConfidenceMen)

Ed Battistella: I really enjoyed The Confidence Men, both for the story itself, with its wonderful writing, and for its insights about the history of cons and mentalism. How did you discover the story of Elias Henry Jones and Cedric Waters Hill?

Margalit Fox: Thank you, Ed! This book, my fourth, is especially dear to my heart because of the eye-popping nature of its true story—the tale of a prison break so bizarre it should never have worked. What delighted me every bit as much as the story itself was the way in which I encountered it: thumbing through a dusty, long-out-of-print book, looking for something else entirely.

About three years ago, when my previous book, Conan Doyle for the Defense, was in production, I began casting about for what to write next. I was vaguely thinking of doing something about the nature of identity as seen through the exploits of pathological impostors—people like Frank Abagnale, of Catch Me if You Can fame, or Ferdinand Demara, the subject of Robert Crichton’s 1959 biography, The Great Imposter, and the Hollywood adaptation, starring Tony Curtis, released the next year.

From my home library, I took down one of my favorite volumes: Grand Deception: The World’s Most Spectacular and Successful Hoaxes, Impostures, Ruses and Frauds, a 1955 anthology edited by Alexander Klein. I knew it contained at least one piece on imposture, but what caught my eye was an essay with the most tantalizing title I’ve ever seen on a work of nonfiction: “The Invisible Accomplice.” That essay, written by my protagonist, the Welsh artilleryman Elias Henry Jones, and originally published in the 1930s, recounted his escapade in brief. It led me back to The Road to En-dor, Jones’s book-length memoir of 1919.

I’ve always been a huge fan of POW-escape narratives, both on the screen and the printed page—hardy perennials like The Great Escape, The Wooden Horse and Stalag 17. But Jones’s caper—rife with cunning, danger and moments of high farce that rival anything in Catch-22—was like nothing I’d seen before: It entailed no tunnelling, no weapons and no violence, all the stuff of traditional prison-camp breakouts.

Instead, Jones and his confederate, the Australian flier Cedric Hill, set in motion an ingeniously planned, daringly executed con game, worked bit by bit on their Ottoman captors—an elaborate piece of participatory theater entailing fake séances, magical illusions, secret codes and a hunt for buried treasure, with clues that appeared to have been planted by ghosts. If all went according to plan, the camp’s iron-fisted commandant would gleefully escort Jones and Hill along their escape route, with the Ottoman government paying their travel expenses. If their ruse was discovered, it would mean a bullet in the back for each of them.

Forget pathological imposters—here was my story! And to my wild delight, some quick research confirmed that with the exception of Hill’s own memoir, The Spook and the Commandant, published posthumously in 1975, there had been no book on the caper in the intervening hundred years. So in telling Jones and Hill’s story, I had not only the pleasure of levering it out of the crevice in history into which it had slipped, but also the privilege of a century’s hindsight, with its attendant advances in psychology. Those advances—in particular a spate of fascinating studies of magic, deception, confidence schemes and the implanting of false beliefs—let me answer the question that had beckoned since I first encountered Jones’s work: How could his escape plan, preposterous in all respects, actually have succeeded?

So began my enraptured involvement with Jones and Hill’s caper, one of the only known instances of a con game being used for good instead of ill. (On reading my proposal for The Confidence Men, my longtime literary agent, an elegant, erudite woman in her 70s, burst out: “Is this for real? These guys are wild!” I was happy to tell her that yes it is, and yes they are.)

EB: The Confidence Men was set roughly in the same time period as your book Conan Doyle for the Defense. Have you got a particular interest in British history of the early twentieth century or just in great mysteries of the past?

MF: I hadn’t planned to return to that period, so I can honestly say that the synchronicity is pure coincidence. But on second thought, one of the things that makes the early 20th century so fascinating (and a fount of wonderful real-life stories) is that it was very much a liminal time in social and intellectual history. On the one hand, you had the continued, hurtling onslaught of modern science, a development that had been a hallmark of the Victorian Age. On the other, you had the persistence—or, more accurately, the renewal, brought about by the Great War—of mass interest in spiritualism.

MF: I hadn’t planned to return to that period, so I can honestly say that the synchronicity is pure coincidence. But on second thought, one of the things that makes the early 20th century so fascinating (and a fount of wonderful real-life stories) is that it was very much a liminal time in social and intellectual history. On the one hand, you had the continued, hurtling onslaught of modern science, a development that had been a hallmark of the Victorian Age. On the other, you had the persistence—or, more accurately, the renewal, brought about by the Great War—of mass interest in spiritualism.

What seems counterintuitive to us, looking back from our 21st-century prospect, is that some of the most influential figures in both movements were one and the same. The distinguished English physicist Sir Oliver Lodge, for instance, wrote a deeply influential book, Raymond (1916), about his efforts—successful, he believed—to contact the spirit of his son, who had been killed in Flanders. And Sir Arthur Conan Doyle himself, a trained physician and the creator of the single most rationalist character in world letters, was also an ardent spiritualist.

Though the spiritualist beliefs of men like these look risible today, it’s crucial to remember that the mass-communications technologies of the period—radio, the telephone, the phonograph—had advanced to the point where they were beyond the ken of most laymen: To the general public, they seemed to be quasi-magical devices that let voices travel through the ether as if by magic, and bygone men and women speak, via wax cylinders, as if from beyond the grave. So among men of science of the period, an authentic empirical question was this: Given technology’s power to do all these miraculous things, why shouldn’t communication across the ultimate divide—between the world of the living and the world of the dead—be possible, too? I now realize that Conan Doyle and his cohort are the connective tissue that links my previous book to this one.

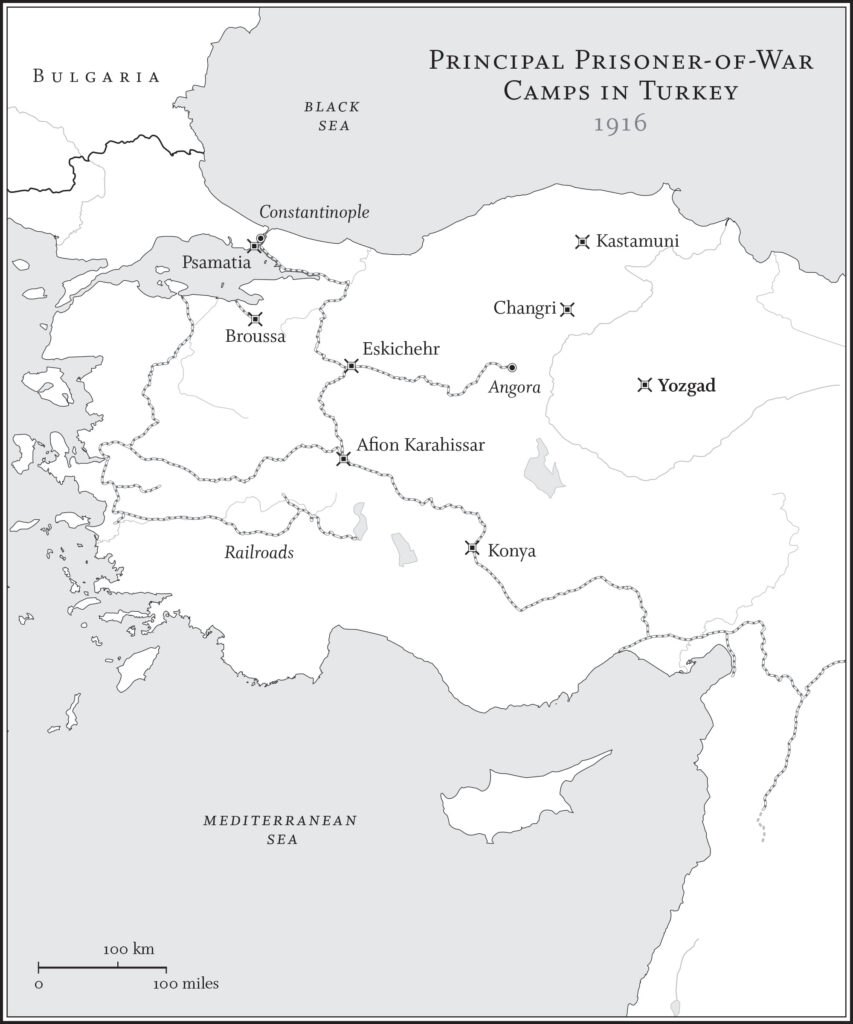

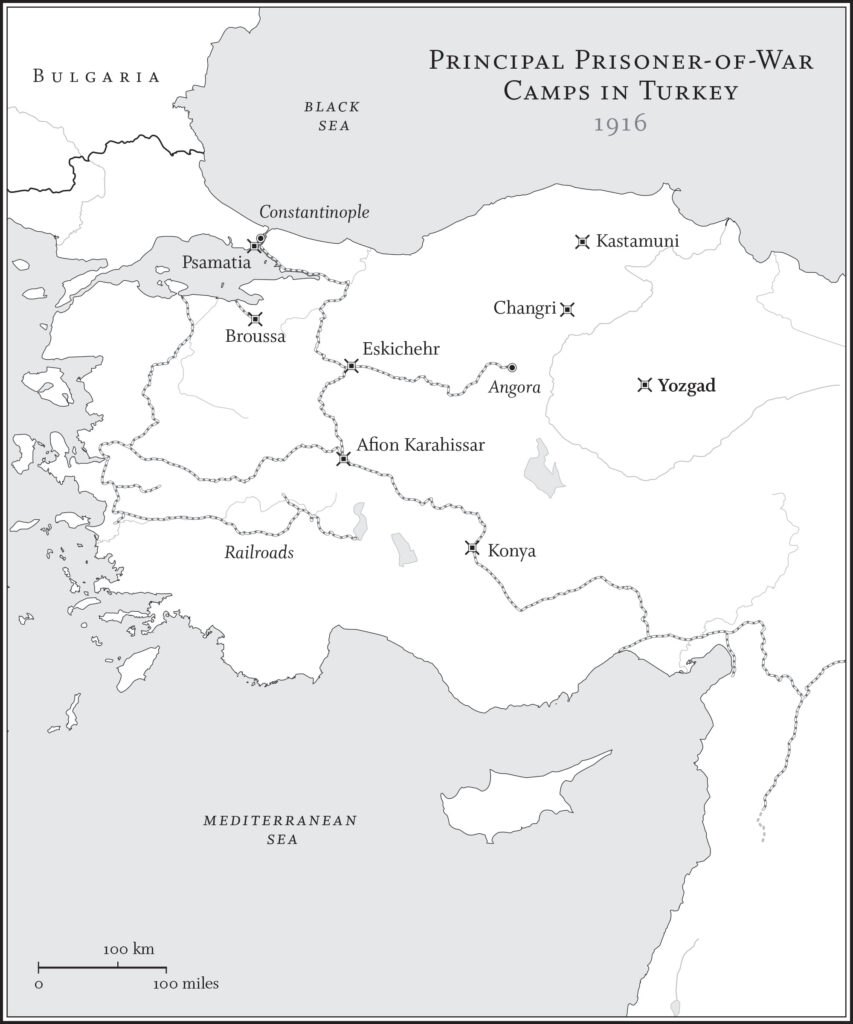

In addition, what unites all my books, from Talking Hands (about a team of linguists decoding a sign language newly emerged in a Deaf Bedouin community) through The Riddle of Labyrinth (the story of the race to decipher the mysterious Bronze Age script known as Linear B) to Conan Doyle for the Defense (about Sir Arthur’s real-life investigation of a wrongful murder conviction) is that they’re all heuristic: They all center on the step-by-step process of advancing from an agnostic state to one of knowing. All involve intellectual treasure hunts of one sort or another—and in the case of The Confidence Men, an actual, cunningly designed treasure hunt, engineered to spring our heroes from an isolated prison camp high in the mountains of Anatolia.

map credit: Jonathan Corum

EB: What was the most difficult aspect of this project? I was amazed at the level of historical detail.

MF: How lovely, thanks! I don’t want to say that this book practically wrote itself, because (a) no book is easy, and (b) that would be the most hubristic tempting of the Fates I could imagine. However … one of the most remarkable things about this story is that it cleaved naturally into the classic three-act structure: the men’s imprisonment, their longing for escape, and their building of the Ouija board in Act I; the conception and playing of the con game in Act II (culminating at the end of the act in a disaster that capsizes their entire plan on the eve of their escape); and the dark turn the story takes in Act III, with our heroes attempting to salvage their plan by having themselves committed to a Turkish insane asylum, before the triumphant resolution.

I literally had to do no restructuring of the story whatsoever to create the basic armature of the book—something that almost never happens when one writes narrative nonfiction. I also spent about a year, as I do for all my books, reading background literature on a host of subjects, including the relevant work in psychology and social history; the history of the war’s Ottoman theater—far less well known to Americans than the Western Front—along with memoirs by other POWs in that theater. But even so, I found I was able to interleave the material from these works in and out of the very sturdy structure that Jones and Hill’s story had given me.

So in the end, perhaps because I’ve been researching and writing books for some 20 years now, I found that The Confidence Men leapt onto the page with a kind of unitary ease that I hadn’t experienced before. And now that the book is out, it’s become apparent that its three-act structure is readily discernible by others: I’ve been spending a very happy summer in conference calls with a string of Hollywood producers who want to option it—a fascinating kind of occupational anthropology for an old-school print gal like me.

EB: In some ways, this story of pseudoscience, cons, and spiritualism is a cautionary tale as well as a thrilling escape story. Is there a lesson here for people today?

MF: Indeed, Jones intended The Road to En-dor to be a cautionary tale about how remarkably easy it is to become a spiritualist charlatan, a species of war profiteer that flourished between 1914 and 1918 to wring dividends from gold-star families. (Jones took his title from “En-Dor,” Rudyard Kipling’s bitter poem of 1919. In it, Kipling, who had lost a son in World War I, decries such mountebanks: “The road to En-dor is easy to tread/For Mother or yearning Wife./There, it is sure, we shall meet our Dead/As they were even in life. …” Kipling’s title invokes the biblical Witch of Endor, from the First Book of Samuel, whom Saul asks to conjure Samuel’s spirit.)

Though I hadn’t set out to relate Jones’s story to our own time, it turned out to be remarkably relevant. As I’ve written in The Confidence Men and elsewhere, the process by which a master manipulator instills and sustains belief (a subtle psychological art known as “coercive persuasion”) impeccably explains the wide popular delusions that have suffused our post-2016 landscape—from the contention that top Democrats are running a sex-trafficking ring out of a pizza parlor to the belief that Covid vaccinations scramble the recipient’s DNA. As Michael Dirda of The Washington Post wrote in his thoughtful review of The Confidence Men: “We are all vulnerable to psychological manipulation. More than ever, with no sure footing in our rabidly media-dominated world, the only sensible course left us is to tread very, very carefully.”

EB: As a writer, what do you keep foremost when you are drafting and revising? I think in some ways being a writer is like being a magician, where you have to attend to your task and to the audience.

MF: I’ve always loved best the two endpoints that bracket the actual writing of a book. The first comes after I’ve spent that initial year reading the literature. At the end of that time, I’ll have anywhere from five hundred to a thousand typed pages of notes. I then go through them, page by page, on a very large table (I usually hole up in the library at Columbia University, to which I have blessed access as an alumna of their journalism school), coding every paragraph thematically and marking the quotes and anecdotes I want to use. This process can take days—even weeks—but at the end of it, there is the great pleasure of getting to see what Henry James called the figure in the carpet. That gives me the first strong sense of what the structure and content of the book will be.

Fast-forward a year or so, to when the entire first draft has been written. The thing I love most of all in the entire process is the buffing and polishing one does at this stage—wielding finer and finer grits of sandpaper until the text shines like a mirror.

EB: You made your journalistic bones, so to speak, in obituaries, which is a fairly concise form of storytelling. Do you see some parallels between writing engaging obituaries and thrilling long form histories?

MF: Since I was trained in the Chomskyan tradition of linguistic innatism, I can say that I truly believe all writers come into the world hard-wired for either long-form or short-form work. I happen to be a long-form writer in my bones, and never in my wildest professional dreams did I imagine that I’d spend three decades on daily newspapers. But I can assure all would-be book writers that that life turns out to be sublime training for long-form writing … because a properly written newspaper article is simply a book in microcosm: A story of a thousand words, say, has only to be gridded up a hundred times until you find you’re holding a book in your hands.

The reason for this is fascinating, and it harks back to the early days of modern American journalism. The structure of the contemporary news story was established during the Civil War, thanks to the prevalence of one of those quasi-miraculous communications technologies: the telegraph. For the first time, war correspondents did their reporting in the field and then cabled their stories back to their editors in Boston or Baltimore or New York or wherever. But as with many new technologies, this one was buggy, and the lines often went down. As a result, reporters learned to triage their dispatches, sending the broadest-based, most essential information first, so that if the lines did go down, at least their editors would have basic information to put in the next day’s paper. If the lines came back up again later, the reporters would send finer and finer-grained information in succeeding dispatches—material that it would be nice for readers to have, but that wasn’t essential. And … voila! Thus emerged the classic “inverted-pyramid” structure of the modern news story—broad information at the top, progressively finer stuff at the bottom—which remains the standard today.

This structure has endured unchanged for a century and a half because it’s cognitively perfect: It is an information-processing model, pure and simple. Anyone who’s ever been a teacher knows this: You don’t start the semester (or an individual lesson) with the background detail. You start with the broad stuff, and work your way down over time. Nonfiction books turn out to rely on this model just as heavily: They’re identical in structure to news stories because to be accessible to the reader, they have to be—the only truly significant difference is one of bulk.

A last historical note: It’s absolutely fascinating to go back in the historical clips and see the inverted-pyramid form taking shape. If you look at the coverage of Lincoln’s assassination, for instance, you can see immediately that the form was still in transition in 1865: Some newspapers were already using the inverted pyramid, while others continued the former tradition of straight-ahead, leaden chronology. In those papers, you’ll get stories—shocking to read today—that start, in effect [my paraphrase]: “The president, Mrs. Lincoln and a party of distinguished friends sallied out last night to Ford’s Theater to see that entertaining play, Our American Cousin.” There follow several more paragraphs of blah-blah-blah-ing about the play, the theater party and the cast. Only then, in about Paragraph 4 or 5, does the reporter get around to “a shot rang out.” Talk about burying your lede—the cardinal sin of newswriting today!

EB: Along with your work at the Times, your background included training as a cellist and as a linguist. How do those experiences make themselves felt in your writing?

MF: I always tell young journalists that a life in music is the single best preparation for being I writer that I can conceive of: It gives you an acute sense of tone and color and cadence and pacing—all essential arrows in the writer’s quiver. The number of serious musicians one finds in big-city newsrooms is striking: At the Times, we have a delightful chamber-music group, in which I still play, called the Qwerty Ensemble. Our rehearsals have been in abeyance as a result of Covid, of course, but we’re all eager to resume playing together.

And needless to say, my linguistics training—I did bachelor’s and master’s degrees in the field at SUNY-Stony Brook—helps me as a writer every hour of every day. When I was studying linguistics (long before I had any thoughts of a writing career) I was especially drawn to the subfields of poetics and stylistics—the analysis of what’s happening metrically, syntactically, semantically, phonetically, et al., that makes literary language resonate in the particular ways it does. Even now, nearly 40 years after that education, the conscious awareness of those factors aids me immeasurably in writing, particularly in the 10,000-grit sanding process described above.

EB: Did you ever have aspirations to be a mentalist or con artist? Or do you now?

MF: Good Lord, no! (Unless you’re willing to bake me a cake with a file in it.)

EB: Thanks for talking with us. I hope you find many more untold stories.

MF: It’s been my pleasure, Ed. But I’m now fascinated by the wonderful paradox contained in your last sentence. Any story that I’m lucky enough to come across in the literature, as I did with The Confidence Men, is by definition a “told” story. If it were truly “untold,” then I’d have no way of finding it to lever it out of that historical crevice.

This actually brings us back to pathological imposters. One reason (besides stumbling upon Jones’s story) that I ultimately decided not to write about them is that we can only ever know about the ones who slip up: the men and women who get caught in the act and have books and articles written about them. The most brilliantly successful imposters remain, by definition, indetectable.

So through the twin paradoxes of the “told story” and the “known imposter” we’ve come full circle!

Dr. Michael A. Rousell is a teacher, psychologist, and professor emeritus at Southern Oregon University. Rousell studied life-changing events for over three decades and established his expertise by writing the internationally successful book Sudden Influence: How Spontaneous Events Shape Our Lives (2007). His pioneering work draws on research from a wide variety of brain sciences that show when, how, and why we instantly form new beliefs. He lives with his spouse in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Dr. Michael A. Rousell is a teacher, psychologist, and professor emeritus at Southern Oregon University. Rousell studied life-changing events for over three decades and established his expertise by writing the internationally successful book Sudden Influence: How Spontaneous Events Shape Our Lives (2007). His pioneering work draws on research from a wide variety of brain sciences that show when, how, and why we instantly form new beliefs. He lives with his spouse in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. MR: Surprise boosts attention and facilitates long-term memory. So, use it as much as you can. Here’s an example I use in my teacher-preparation classes. I ask my students to predict the correlation between self-esteem and school success. Is it positive, as one increases, so does the other, and if so, is it strong, moderate, or weak? I give them a moment to think about it, then right down their answers, then discuss it within their groups. After a minute, I tell them to openly discuss their responses. The vast majority predict a strong positive correlation. They now expect me to begin a lesson on how to raise students’ self-esteem. I tricked them. I tell them that the correlation does not even exist. This surprises them, “What the,” and this surprise drives curiosity, a need to know. Now they listen thoughtfully as I give challenging examples. You know, the bully who loves himself but gets low grades, victims of ridicule that earn great grades but feel horrible about themselves. If I had simply lectured on the topic, it would have the same results as any lecture material. But because I surprised them, they will all remember this lesson and maybe even try to surprise other teachers. The media and entertainment use surprise strategically all the time to keep your attention. Think of news teasers, “And you thought dogs were your best friend—stay tuned. You won’t believe it.”

MR: Surprise boosts attention and facilitates long-term memory. So, use it as much as you can. Here’s an example I use in my teacher-preparation classes. I ask my students to predict the correlation between self-esteem and school success. Is it positive, as one increases, so does the other, and if so, is it strong, moderate, or weak? I give them a moment to think about it, then right down their answers, then discuss it within their groups. After a minute, I tell them to openly discuss their responses. The vast majority predict a strong positive correlation. They now expect me to begin a lesson on how to raise students’ self-esteem. I tricked them. I tell them that the correlation does not even exist. This surprises them, “What the,” and this surprise drives curiosity, a need to know. Now they listen thoughtfully as I give challenging examples. You know, the bully who loves himself but gets low grades, victims of ridicule that earn great grades but feel horrible about themselves. If I had simply lectured on the topic, it would have the same results as any lecture material. But because I surprised them, they will all remember this lesson and maybe even try to surprise other teachers. The media and entertainment use surprise strategically all the time to keep your attention. Think of news teasers, “And you thought dogs were your best friend—stay tuned. You won’t believe it.”

Follow

Follow Dr. Margaret Perrow is Professor of English and English Education at Southern Oregon University, where she has taught since 2006. She has a BA from Yale University and an MA and PhD in Language, Literacy, and Culture in Education from the University of California, Berkeley and is the co-director of the Oregon Writing Project at SOU. Prior to joining Southern Oregon University, she worked at the Bay Area Coalition for Equitable Schools.

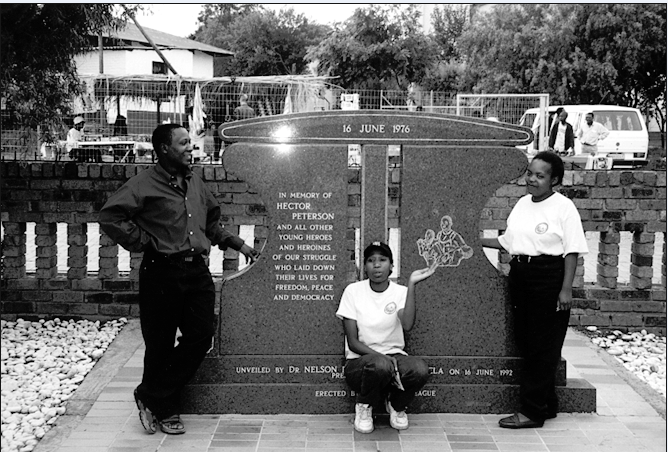

Dr. Margaret Perrow is Professor of English and English Education at Southern Oregon University, where she has taught since 2006. She has a BA from Yale University and an MA and PhD in Language, Literacy, and Culture in Education from the University of California, Berkeley and is the co-director of the Oregon Writing Project at SOU. Prior to joining Southern Oregon University, she worked at the Bay Area Coalition for Equitable Schools. On the professional front, I had been teaching in an alternative education (GED) program for young adults in San Francisco. My master’s thesis had investigated their perceptions of learning — what learning meant for them — and I was feeling around for a good related focus for my PhD dissertation. South Africa had recently held its first democratic elections after years of anti-apartheid struggle, and it seemed like an interesting place to do a similar study, looking at what learning might mean in alternative education settings for young adults in a country that was undergoing rapid socio-economic and political transition. Post-apartheid South Africa was also a good bet for finding research funding at the time. Several grants, including a Fulbright dissertation fellowship, made it possible for me to spend 18 months in Johannesburg. A series of fortuitous connections led me to the Joint Enrichment Project (JEP). JEP was a prominent youth-development NGO with strong roots in anti-apartheid resistance. I was privileged to be invited into JEP as a visiting researcher, where I got to know a group of young adults from Soweto, the townships outside Johannesburg.

On the professional front, I had been teaching in an alternative education (GED) program for young adults in San Francisco. My master’s thesis had investigated their perceptions of learning — what learning meant for them — and I was feeling around for a good related focus for my PhD dissertation. South Africa had recently held its first democratic elections after years of anti-apartheid struggle, and it seemed like an interesting place to do a similar study, looking at what learning might mean in alternative education settings for young adults in a country that was undergoing rapid socio-economic and political transition. Post-apartheid South Africa was also a good bet for finding research funding at the time. Several grants, including a Fulbright dissertation fellowship, made it possible for me to spend 18 months in Johannesburg. A series of fortuitous connections led me to the Joint Enrichment Project (JEP). JEP was a prominent youth-development NGO with strong roots in anti-apartheid resistance. I was privileged to be invited into JEP as a visiting researcher, where I got to know a group of young adults from Soweto, the townships outside Johannesburg.

Writer Nathan Harris has a MFA from the

Writer Nathan Harris has a MFA from the  EB: What was the historical research like for The Sweetness of Water? It must have been extensive.

EB: What was the historical research like for The Sweetness of Water? It must have been extensive.

MF: I hadn’t planned to return to that period, so I can honestly say that the synchronicity is pure coincidence. But on second thought, one of the things that makes the early 20th century so fascinating (and a fount of wonderful real-life stories) is that it was very much a liminal time in social and intellectual history. On the one hand, you had the continued, hurtling onslaught of modern science, a development that had been a hallmark of the Victorian Age. On the other, you had the persistence—or, more accurately, the renewal, brought about by the Great War—of mass interest in spiritualism.

MF: I hadn’t planned to return to that period, so I can honestly say that the synchronicity is pure coincidence. But on second thought, one of the things that makes the early 20th century so fascinating (and a fount of wonderful real-life stories) is that it was very much a liminal time in social and intellectual history. On the one hand, you had the continued, hurtling onslaught of modern science, a development that had been a hallmark of the Victorian Age. On the other, you had the persistence—or, more accurately, the renewal, brought about by the Great War—of mass interest in spiritualism.