Maggie Alvarez

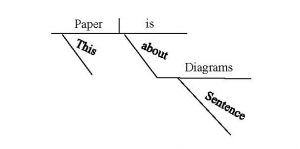

Grammar is a difficult concept for many individuals to understand, and it is even more difficult to teach. One common teaching technique that was popular at the start of the 20th century is sentence diagramming, which is a visual representation of the grammatical structures within sentences. Sentence diagrams influenced grammar education for decades; however, most students today have never even seen or heard of a sentence diagram. What happened to this form of grammar instruction? This paper will observe the process and history of sentence diagramming to discover when and why the technique was phased out of the American school system and identify if the process should be reestablished in curriculum.

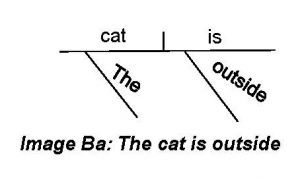

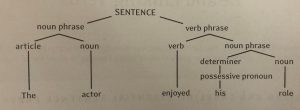

In its most basic form (identified in Image A), a traditional sentence diagram divides a sentence into two parts: the subject phrase and the predicate phrase.  All elements of the subject phrase sit on the left side, and all elements of the predicate phrase are located on the right; separating the subject and predicate is a short, straight line. In this section, we[1] will examine three different but common formats for sentence diagrams (Vitto 50).

All elements of the subject phrase sit on the left side, and all elements of the predicate phrase are located on the right; separating the subject and predicate is a short, straight line. In this section, we[1] will examine three different but common formats for sentence diagrams (Vitto 50).

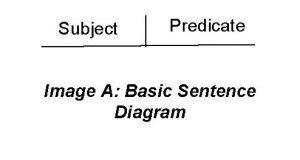

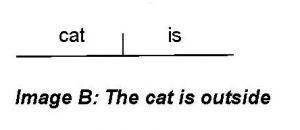

Let us examine the sentence: The cat is outside. The first step before diagramming is to identify the subject and predicate. In this case, subject equals “cat” and predicate equals “is.” Image B places the subject and predicate into their proper places. However, the diagram is not complete as it lacks the words “the” and “outside.” In any and all sentence diagrams, articles, adjectives, adverbs, and modifying pronouns are placed below the word they modify on a slanted line. Since “the” is a part of the subject phrase and modifies “cat,” it will be placed on the left side beneath “cat.”  Furthermore, “outside” needs to be placed on the diagram. In this context, “outside” is being used as an adverb to identify location. Therefore, the adverb will be placed on a slanted line below the verb it modifies. “Outside” is a part of the predicate phrase, so it will be placed on the right side below “is.” The sentence diagram in Image Ba[2] reflects the final product of the sentence: The cat is outside. Next, we will investigate how to diagram a sentence which includes either a predicate adjective or predicate noun (Vitto 50).

Furthermore, “outside” needs to be placed on the diagram. In this context, “outside” is being used as an adverb to identify location. Therefore, the adverb will be placed on a slanted line below the verb it modifies. “Outside” is a part of the predicate phrase, so it will be placed on the right side below “is.” The sentence diagram in Image Ba[2] reflects the final product of the sentence: The cat is outside. Next, we will investigate how to diagram a sentence which includes either a predicate adjective or predicate noun (Vitto 50).

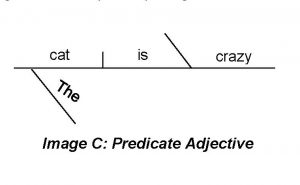

Predicate adjectives and nouns are diagrammed similarly. As they are a part of the predicate phrase, they are located on the right side of the diagram. Unlike articles, adjectives, and adverbs, which are located below the word they modify, predicate adjectives and nouns remain on the same line as the predicate. It is separated from the predicate with a backslash. To show this, we will use the sentences: The cat is crazy and The cat is my pet. Since we already diagrammed a version of this sentence earlier, we know what the subject and predicate are and how they should be formatted. It is also known that “the” modifies “cat,” so the article should be placed beneath the subject on a slanted line. Now, however, the predicate adjective “crazy” needs to be added, which is illustrated in Image C.

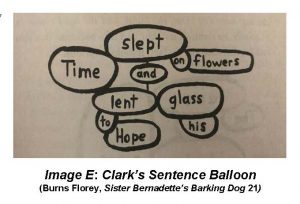

Alonzo Reed and Brainerd Kellogg are recognized as the pioneers of sentence diagramming; however, the concept was actually first created by a lifelong educator named S.W. Clark. The sentence diagrams that most people are familiar with today are an evolved version of Clark’s original work. The practice of sentence diagramming was established in 1860 when Clark published his book A Practical Grammar: In which Words, Phrases, and Sentences Are Classified According to their Offices and Their Various Relations to One Another where he compared “grammar to both geometry (‘an abstract truth made tangible’) and architecture (‘like the foundation of a building’)” (Burns Florey, Sister Bernadette’s Barking Dog 20). The original sentence diagram was formed by a series of balloons, as seen in Image E. Clark thoroughly and confidently believed his method was the best way to teach grammar as “the diagrams are made to render the Analysis of Sentences more perspicuous” (21). While Clark did have a solid understanding of sentence diagramming, his approach with balloons made the sentences difficult to understand and look at. Therefore, in 1877, Reed and Kellogg published their book Higher Lessons in English which introduced an improved version of sentence diagrams to the world. Their diagrams follow the same ideas as Clark, but their approach was better recognized by society as the straight, organized lines made for easy instruction. Both Reed and Kellogg were dedicated educators and were fascinated by the nuances of English grammar. Their attraction (and the amount of unenthusiastic students who struggled with grammatical concepts) led to the evolution of the sentence diagram which became a part of the American public school curriculum…to a point (Burns Florey, Sister Bernadette’s Barking Dog 19-33).

Since we know predicate adjectives and predicate nouns are diagrammed in the same fashion, the sentence The cat is my pet would look similar to Image C. The only difference is “my” which modifies “pet” would need to be placed beneath the word it modifies on a slanted line as shown in Image Ca. Since the overall format of the diagram does not change with the variations of the sentence, it is a beneficial grammar teaching tool. New elements can be added, and once a student recognizes the basic idea of a diagram, it is not difficult to bring in those new grammatical constructions (Vitto 51).

Since we know predicate adjectives and predicate nouns are diagrammed in the same fashion, the sentence The cat is my pet would look similar to Image C. The only difference is “my” which modifies “pet” would need to be placed beneath the word it modifies on a slanted line as shown in Image Ca. Since the overall format of the diagram does not change with the variations of the sentence, it is a beneficial grammar teaching tool. New elements can be added, and once a student recognizes the basic idea of a diagram, it is not difficult to bring in those new grammatical constructions (Vitto 51).

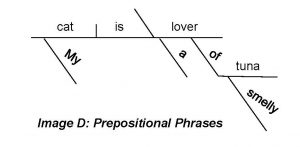

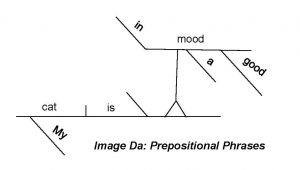

Now, we will add one more new piece to the diagram: prepositional phrases. Prepositional phrases, in general, are also located below the main line as they often function as adjectives and adverbs. The prepositional word itself belongs on a slanted line just as the words “the” and “my” do. The object of the preposition is on a connecting horizontal line which may have modifiers beneath it. For example, let us look at the sentence: My cat is a lover of smelly tuna, which Image D reflects.  Notice how the predicate noun “lover” has both “a” and the prepositional phrase “of smelly tuna” beneath it. There is no limit to how many modifiers a word can have. While it may make for a complicated looking diagram, it is all correct. There are some situations where the predicate adjective is in the form of a prepositional phrase. In these cases, the phrase is put on a pedestal which floats above the main line as identified in Image Da with the sentence: My cat is in a good mood.

Notice how the predicate noun “lover” has both “a” and the prepositional phrase “of smelly tuna” beneath it. There is no limit to how many modifiers a word can have. While it may make for a complicated looking diagram, it is all correct. There are some situations where the predicate adjective is in the form of a prepositional phrase. In these cases, the phrase is put on a pedestal which floats above the main line as identified in Image Da with the sentence: My cat is in a good mood.

Examples B, C, and D show only a few of the various structures one could make with sentence diagrams. With the many different parts of speech and ways to structure sentences, the possibilities are almost endless. In fact, there are many teachers who may present a different style of formatting just for preference.

Sentence diagramming was a national phenomenon throughout America from the moment Reed and Kellogg’s work was published. However, sometime during the 1960s, new research was produced by the Encyclopedia of Educational Research which criticized Reed and Kellogg’s technique stating, “Diagramming sentences … teaches nothing beyond the ability to diagram” (Summers). Furthermore, around that time, teachers began encouraging students to express themselves through writing rather than expressing themselves accurately (Burns Florey, Interview). With no actual educational purpose and a need for expression, the sentence diagram began to die off. The technique was still taught regularly within schools; however, in 1985, the National Council of Teachers of English decided “repetitive grammar drills and exercises [are] a deterrent to the improvement of students’ speaking and writing” (Summers). From that consensus, sentence diagramming became a mostly forgotten teaching technique. There are some teachers today who will integrate sentence diagramming into lesson plans, but those reasons are really only for nostalgia’s sake. There is a more modern style of sentence diagramming, presented in Image F, which is called the sentence tree and is easier to decipher than the traditional form (Vitto 46). Again, however, only a select few of educators across America actually integrate sentence diagramming into their curriculum. The majority of the current generation of students has no idea what sentence diagrams are or how to produce them as it has become a forgotten teaching technique.

Image F: The Sentence Tree (Vitto 46)

However, what would be so harmful in bringing the sentence diagram back? Yes, the process is tedious and the structures can get fairly complicated, but the technique is much more intriguing than a normal lecture on grammar. One of the most difficult concepts teachers have noticed when trying to teach their students about grammar is the process of engagement. As examined in the article, “Student Engagement in the Teaching and Learning of Grammar,” researchers examine the benefits of implementing engaging lesson plans into the curriculum and techniques for creating them. During their study, they realize, “traditional grammar instruction is the only [method] that has a negative impact on students’ writing, and to a compellingly significant degree” (Smagorinsky, et al. 78).

Simply identifying the different parts of speech and having students use them within sentences may not be the most engaging practice for students. Sentence diagrams, on the other hand, “is logical and especially helpful for visual learners, who can see the sentence in non-linear fashion…in addition, kinetic learners, puzzle lovers, and those with a penchant for putting things in their place typically find diagramming simultaneously challenging and satisfying” (Vitto 46). Sentence diagrams can be seen as one huge game for children, so they could be extremely effective for grammar instruction. Also, the clear, concrete ideas are much more effective than the abstract way grammar is currently taught. This teaching technique could have a place in the classroom once again. However, since Smagorinsky et al’s research found that traditional grammar negatively affects student learning, perhaps educators should shift to the more modern approach to diagramming reflected in Image F. The simplicity of the sentence tree would make for easier instruction but would still maintain the puzzling thrill of traditional diagrams. So, perhaps there is still a place for sentence diagrams within American curriculum after all.

Works Cited

Burns Florey, Kitty. Interview with Scott Simon. “Writer’s Subject? Diagramming Sentences.” NPR, 2006.

Burns Florey, Kitty. Sister Bernadette’s Barking Dog. Houghton Mifflin Publishing Company, 2006.

Smagorinsky, Peter, et al. “Student Engagement in the Teaching and Learning of Grammar.” Journal of Teacher Education, vol. 58, no. 1, 2007, pp. 76-90.

Summers, Juana. “A Picture of Language: The Fading Art of Diagramming Sentences.” NPR, 22 August 2014. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6569894. Accessed 15 May 2019.

Vitto, Cindy. Grammar by Diagram. 2nd ed., Broadview Press, 2006.

-

As this is an educational paper, the author is purposefully writing in the first person for some sections in order to engage readers in the teaching technique. ↑

-

It is recommended that all capitalization remains the same when placed within a diagram. Perhaps a teacher may challenge their students to work backwards from a sentence diagram and create the full sentence just by looking at where the words are formatted. By maintaining proper capitalization, the un-diagrammed sentence is much easier to comprehend. ↑

Follow

Follow Gwendolyn Bogard is member of the Honors College at SOU, where she studies Chemistry in preparation for a career in science communication.

Gwendolyn Bogard is member of the Honors College at SOU, where she studies Chemistry in preparation for a career in science communication. Phil Busse is an Oregon writer and publisher. Raised in Wisconsin, he graduated from Middlebury College in Vermont, and began as career as a journalist with the San Francisco Weekly. He has written for the Eugene Weekly and helped start the Portland Mercury, where he was managing editor. Busse is the executive director for the Media Institute for Social Change and is the publisher and editor for the Rogue Valley Messenger, which provides news, entertainment and reviews to southern Oregon.

Phil Busse is an Oregon writer and publisher. Raised in Wisconsin, he graduated from Middlebury College in Vermont, and began as career as a journalist with the San Francisco Weekly. He has written for the Eugene Weekly and helped start the Portland Mercury, where he was managing editor. Busse is the executive director for the Media Institute for Social Change and is the publisher and editor for the Rogue Valley Messenger, which provides news, entertainment and reviews to southern Oregon.

Jordan Hartman is an aspiring writer and photographer based in the Rogue Valley. He has recently graduated from Southern Oregon University with a Bachelor’s degree in English. Jordan has been honing his culinary skills for over eighteen years.

Jordan Hartman is an aspiring writer and photographer based in the Rogue Valley. He has recently graduated from Southern Oregon University with a Bachelor’s degree in English. Jordan has been honing his culinary skills for over eighteen years.