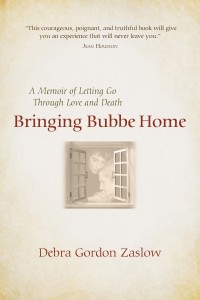

Debra Gordon Zaslow is the author of Bringing Bubbe Home, a Memoir of Letting go Through Love and Death, the story of her 103 year-old grandmother’s final months.

Debra Gordon Zaslow is the author of Bringing Bubbe Home, a Memoir of Letting go Through Love and Death, the story of her 103 year-old grandmother’s final months.

Debra Zaslow is a professional storyteller, writer and teacher whose stories have been published in anthologies that include the Cup of Comfort series, Chosen Tales, Stories told by Jewish Storytellers, and Mitzvah Stories. Her story, “Diving for Love” was a finalist in the Redbook Magazine “Your Love Story” contest. She teaches storytelling at Southern Oregon University, and her CD, “Return Again: Stories of Healing and Renewal,” combines personal narrative with Jewish folktales. You can visit her website at: http://debrazaslow.com/

We sat down to talk about Bringing Bubbe Home.

EB: I really enjoyed Bringing Bubbe Home. Before reading it, I was worried that the story would be depressing but you managed to make it quite uplifting. As a writer, how did you make that happen?

DZ: My goal was to make the story as real and accessible as possible. That meant turning notes (from a journal I kept during Bubbe’s visit) into scenes. I used sensory imagery and dialogue whenever possible. Some of the images were not pleasant, since this death was a visceral decline, along with bodily fluids and odors, but I didn’t want to “whitewash” the true experience. However, keeping it real meant including my feelings and observations, which were often humorous, and therefore lightened the mood. Plus, several scenes where Bubbe and I sat in quiet moments and talked were simply moving and uplifting in themselves. Death has a way of stripping away whatever is not important, so you can focus on what’s really there between people.

EB: Any tips for aspiring memoirists?

DZ: I think it’s important NOT to try to be deep and meaningful. Starting out with an agenda to impart wisdom can really kill a narrative. You simply tell the story. The deeper you go into the scenes with specific details, realistic dialogue, and characterization, the more the metaphors and meaning will emerge and take a shape of their own.

EB: I wanted to ask you a bit more about craft. In addition to being a writer you are also a storyteller. How does your expertise in the art of oral performance inform your work as a writer?

DZ: Unfortunately, not as much as I’d hoped. People assume there is a natural crossover between oral storytelling and written work, but they’re actually quite distinct. In writing you can’t employ the tools of facial expression and body language that a storyteller uses, so you have to develop the craft of revealing emotion, gesture, and expression with words alone. After my first draft of Bringing Bubbe Home, I realized I wasn’t as good a writer as I wanted to be, so I went to an MFA in writing program (Vermont College of Fine Arts) to improve my writing enough to do justice to this important story.

One thing that does crossover, however, is a “sense of story.” Years of feeling audiences’ reactions have given me a sense of what is a tellable story—how to dramatize conflict, move the plot along, and create satisfactory resolution. But, what works orally still has to be converted to a more descriptive language when it’s written down.

EB: You talk about your grandmother as “outliving her personality.” I thought that was a nice way of expressing things. Can you talk a little about that?

DZ: My grandmother had always been a difficult, negative person. She was born in the 1800’s in Russia, and her mother beat her constantly. She grew up to be a tough survivor, who was not pleasant to be with. By the time she came to my house at 103 years old, her mental faculties were declining along with the rest of her body, and her crusty covering of negativity began to slip off, revealing a more luminous core. The caregivers had a hard time believing she was once a negative person.

DZ: My grandmother had always been a difficult, negative person. She was born in the 1800’s in Russia, and her mother beat her constantly. She grew up to be a tough survivor, who was not pleasant to be with. By the time she came to my house at 103 years old, her mental faculties were declining along with the rest of her body, and her crusty covering of negativity began to slip off, revealing a more luminous core. The caregivers had a hard time believing she was once a negative person.

I realize this does not happen with all people who live that long. In fact, sometimes at the end of life, whatever fears and anxieties are present, can solidify and worsen. I think for my grandma, it was a combination of being in the right place at the right time. She had lived alone till she was 101, then after being put in a nursing home against her will, she had been declining with poor care. When we brought her to our home, she was surrounded by love and comfort, and was old enough to have forgotten what she was angry about.

EB: The memoir developed from journals you kept. When did you decide to write the book?

DZ: I knew immediately after my grandma died that I wanted to write a book. People had always said to me “You should write a book,” but I never had anything I wanted to write about. Now I knew I had something to say, and six months of journals to go from. The journaling was a way to keep sane under all the stress, and to keep track of what I knew was a “big “ experience. Eventually the scenes in Bringing Bubbe Home evolved from the notes I’d scribbled down during her visit.

EB: You intersperse the story of your grandmother’s last days with stories of the past, your childhood and hers. How did writing the book help you?

DZ: I wanted to put the experience of being with Bubbe for the last months of her life into context to who she had been, and who she was to me. I began writing stories from her past and my past, which is of course, our shared history. It was emotionally very difficult to write the stories of her abuse, and how that abuse trickled through the generations in my family. It took me sixteen years to complete the book! Ultimately, though, it not only deepened the memoir, but it allowed me to see my own life in a clearer context.

EB: You talk a lot about your family in the book, which is set in the late 1990s. Were they involved in the writing process? Did you share the drafts with them as you wrote? How did they like the book?

DZ: My family endured not only the months with Bubbe, but also my immersion in the writing process for many years! I didn’t share much with them during the process because I was committed to writing what I felt was the truth, without their input. I write very honestly about the difficulties inherent in dealing with death in the middle of family life, including how our teenagers were somewhat resistant to the whole process. In the beginning I was angry with my husband because I felt abandoned by him when I was overwhelmed with caring for Bubbe. Part of the arc of the story was my realization (after spending months facing the family history) that my abandonment issues stemmed from my mother, not David.

I let David read a draft a few years before it was published just to make sure he was ok with my honesty about our relationship. Fortunately, he was a really good sport about it. Now that he’s reading the final product, he sees himself as a “wisdom character,” who acts as a foil to me as the stressed-out narrator. My daughter, who is a better writer than I am, gave the book a thumbs-up. My son is reading it now, and he says it’s very emotional to revisit those early teen years.

EB: This is very much a Jewish story, with religious details and filled with Yiddish and the immigrant voice of your grandmother, but the themes are more universal. As you were writing it, how did you imagine your audience?

DZ: I pretty much imagined my audience was me—female, Jewish, Baby boomer. But, now that the book is out, I’m surprised how universal the appeal is. People who are not Jewish relate to an immigrant grandparent, no matter where they came from. And men are loving the book, too. Everyone seems to be moved by the honesty with which family life and the dying process are portrayed.

EB: Despite the serious topic, there were some very funny scenes in the book also, especially the reminiscence when your mother and her friend Ruth are psychoanalyzing the neighborhood. Have you considered writing humor?

DZ: I can’t help writing humor, because I see the ridiculous side of everything. I think good memoir looks at all facets of the story. My mother happened to be a suburban, white-collar alcoholic, but she had a singular style. I’ve learned from storytelling that audiences love to laugh, and most experiences have funny moments, even if only in retrospect. The audience is more willing to go deep with you into pain and poignancy, once you’ve gained their trust with laughter.

EB: You include book group discussion questions. Do you have any thoughts about the different experience of reading the book alone versus discussing it in a group?

DZ: There are three book groups reading “Bubbe” right now (one in Ashland, one in Corvallis, and one in Baltimore) that I will meet with soon. When I give talks or readings, the discussions afterward are always lively and compelling. The book brings up many questions, particularly for readers who are facing decisions about an elder in the family. Often people are eager to share their experiences and thoughts about the recent death of their parent or grandparent. As Baby Boomers age, death is becoming a more accepted topic. This book is perfect for a book group discussion, since it brings up these very topical issues in an unflinching way.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

Dz: THANK YOU!

Follow

Follow