Years ago, a friend complained that everyone was so busy writing books that they had no time to read books. She was talking about people with no time to read her books, but you get the idea. I still don’t have time to post to Goodreads or Amazon, but I did commit to a lot of summer reading and to some mini-reviews. Here they are.

Last Days by Brain Everson– A bizarre but compelling tale of a cop kidnapped by a mutilation cult. Rod Serling meets Stephen King.

Freakonomics by Steven Levitt and Stephen Dunker–I’ve been wanting to read this for a while but kept putting it off (no incentive, I guess). It was excellent—informative and stylistic. It would be fun to do a course using this, Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational and Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s Nudge.

The Notebooks of Raymond Chandler –Almost all of Chandler’s notebook were destroyed at his death. This included some of the material from the two black loose-leaf notebooks that escaped including lists of similes (a face like a collapsed lung), Chandlerisms (She threw her arms around my neck and nicked my ear with the gunsight), slang, and drafts of sketches of scenes and characters.

A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles–Towles’s meditation on how to live a meaningful, even exemplary, life in difficult circumstances. Plus a lot of great Soviet-era history and spycraft. Top notch.

Exhalation by Ted Chiang –A great collection of speculative fiction – time travel, artificial life, free will, memory and more –by the writer who gave us The Story of Your Life. Chiang’s work is thoughtful and thought-provoking and optimistic. Linguists will especially like The Truth of Fact, The Truth of Feeling and The Great Silence.

How to Love a Country by Richard Blanco—Richard Blanco visited Ashland this summer for a series of workshops and reading which gave me the opportunity to delve into his latest poetry collection. Evocative, accessible writing about place, justice, belonging, exile, love and family, with a spectacular landscape piece in the epic “American Wandersong.”

The Dictionary Wars: The American Fight Over the English Language by Peter Martin— I reviewed this for Choice so I won’t repeat that, but suffice it to say it’s a compelling addition to the story of American lexicography with Noah Webster at the center.

An American Language: The History of Spanish in the United States by Rosina Lazano—This is a detailed and thought-provoking history of Spanish from the times of westward expansion through World War II covering of legal, political, and social issues as arising in keys states (New Mexico, Arizona, California, and more), and more all of which informs present-day debates. Great insights. The main drawback is that the book still read like a dissertation.

Southern Oregon Beer by Phil Busse—The story of the Jacksonville origins of southern Oregon beer, the impact of prohibition and the sustainability of the hops industry and the re-emergence of Southern Oregon as a brewing destination in the late twentieth century. Engagingly written, well documented and illustrated with both historical and contemporary photos.

The Prisoner of Guantanamo by Dan Fesperman—This is the first book I’ve read by Fesperman. It seemed to start slowly, but once I got used to the characters and figured out who was who, I was hooked. There was plenty of unpredictability and enough cynicism to capture the intelligence community milieu. I’m ready for more Fesperman.

Dr. Seuss and Mr. Geisel: A Biography by Judith Morgan and Neil Morgan— I had been wanting to read this Seuss bio for some time and it didn’t disappoint.

Engaging and packed with both information and insights about Seuss, the publishing industry, and sweep of the twentieth century.

The Crossword Century: 100 Years of Witty Wordplay, Ingenious Puzzles, and Linguistic Mischief by Alan Connor–Some interesting information but it felt like the author ran out of material quickly and had to fill the book crossword trivia. Ho hum.

Real Tigers by Mick Herron–I started reading Mick Herron last year–Slough House around Thanksgiving, Dead Lions at Spring Break, and now Real Tigers. Herron is darkly funny and the intriguing concept involves what happens to intelligence agents who screw up or become unreliable. They are assigned to Jackson Lamb’s Slough House, where they are given busy work in hopes that they will resign or quietly fade away. But the slow horses of Slough House manage to continually stay in the game thwarting the designs of the careerists at Regent’s Park.

Apex Hides the Hurt by Colson Whitehead– A hilarious sendup of American culture, following in the footsteps of John Henry Days. A town with an identity crisis based in racial history and, best of all, the protagonist is a nomenclature consultant without a name. But with an inflected toe. What name will he choose?

Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny Kate Manne–Insightful treatment of the distinction between “misogyny” and “sexism.” As she notes, the argument extendible to racism and other form of prejudice and injustice). It was interesting to read this in conjuction with Zerubavel’s Taken for Granted.

Manne writes well (and has a knack for terminology like “himpathy” and “misogynoir” and gritty real world examples) however, I thought at times the writing was still too dense.

Because Internet by Gretchen McCulloch—Filled with clever examples and histroical insight, McCullogh’s book shows nicely that internet language is written speech, which its own conventions and, yes rules. BTW, there’re emojis, memes, and more! A good gift for prescriptivists, if you are included to gift them. And I’m thinking about how to incorporate this and Lynne Murphy’s The Prodigal Tongue in the history of English class.

Born to Run by Bruce Springsteen–I started this last summer, but didn’t have time to finish. This summer I did, to the background of Western Stars and Blinded by the Light. Born to Run has Springsteen’s voice and imagery. And like the stories he tells in concerns, there are moral tales and wacky adventures throughout. Springsteen presents himself as determined and tough but vulnerable and striving, which seems about right for a guy from New Jersey.

Taken for Granted by Evitar Zerubavel–Taken for Granted is about the theory of markedness—asymmetry in language and culture—a topic that I have a long standing interest in. Zerubavel’s book brings together the social and cultural aspects of asymmetry. A solid non-academic style, but the examples are sometimes dated and some terms could have been defined more sharply.

Things Too Big to Name by Molly Tinsley—A literary thriller seamlessly weaving together of three stories covering in different time frames and themes, ultimately centered the realities love, goodness, fidelity, justice, and sacrifice. Oh, and the protagonist is a retired English professor living in the mountains near the fictional town of Pine Springs, Oregon.

Catch and Release by Les AuCoin—A political memoir that sparkles with heart and humanity and tells us all what democracy and leadership are about. AuCoin went into political in the “Ask not what your country can do for you” era and his witty, well-crafted memoir tells us not just about how things were in the past but what is missing today.

Follow

Follow In a fit of sanity, award-winning writer Molly Best Tinsley resigned from the civilian faculty of the US Naval Academy and moved west to write full-time. She is the author of My Life with Darwin (Houghton Mifflin) and Throwing Knives (Ohio State University Press), she also co-authored Satan’s Chamber (Fuze Publishing) and the textbook, The Creative Process (St. Martin’s). Her more recent books are the memoir Entering the Blue Stone and another Victoria Pierce spy thriller, Broken Angels, the sequel to Satan’s Chamber. She is also the cofounder of

In a fit of sanity, award-winning writer Molly Best Tinsley resigned from the civilian faculty of the US Naval Academy and moved west to write full-time. She is the author of My Life with Darwin (Houghton Mifflin) and Throwing Knives (Ohio State University Press), she also co-authored Satan’s Chamber (Fuze Publishing) and the textbook, The Creative Process (St. Martin’s). Her more recent books are the memoir Entering the Blue Stone and another Victoria Pierce spy thriller, Broken Angels, the sequel to Satan’s Chamber. She is also the cofounder of

Mary Gently is an aspiring historian based in the Rogue Valley. She recently graduated from Southern Oregon University with a Bachelor’s degree in History and a minor in Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies. She graduated Summa Cum Laude with Departmental Honors and is the recipient of the Arthur S. Taylor Award for Outstanding Student in History 2018-2019. She intends to begin a Ph.D. program in History in the fall of 2020. Mary enjoys traveling, watching classic movies, and drinking craft beer.

Mary Gently is an aspiring historian based in the Rogue Valley. She recently graduated from Southern Oregon University with a Bachelor’s degree in History and a minor in Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies. She graduated Summa Cum Laude with Departmental Honors and is the recipient of the Arthur S. Taylor Award for Outstanding Student in History 2018-2019. She intends to begin a Ph.D. program in History in the fall of 2020. Mary enjoys traveling, watching classic movies, and drinking craft beer.

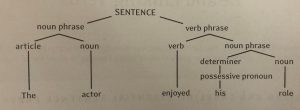

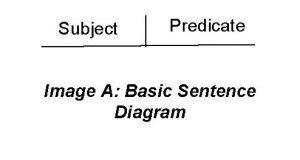

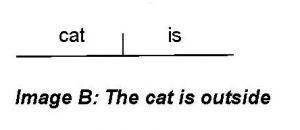

All elements of the subject phrase sit on the left side, and all elements of the predicate phrase are located on the right; separating the subject and predicate is a short, straight line. In this section, we

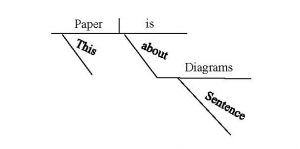

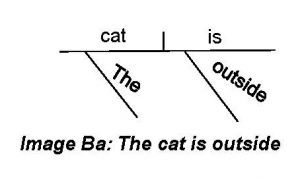

All elements of the subject phrase sit on the left side, and all elements of the predicate phrase are located on the right; separating the subject and predicate is a short, straight line. In this section, we Furthermore, “outside” needs to be placed on the diagram. In this context, “outside” is being used as an adverb to identify location. Therefore, the adverb will be placed on a slanted line below the verb it modifies. “Outside” is a part of the predicate phrase, so it will be placed on the right side below “is.” The sentence diagram in Image Ba

Furthermore, “outside” needs to be placed on the diagram. In this context, “outside” is being used as an adverb to identify location. Therefore, the adverb will be placed on a slanted line below the verb it modifies. “Outside” is a part of the predicate phrase, so it will be placed on the right side below “is.” The sentence diagram in Image Ba

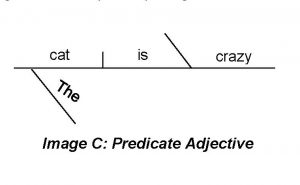

Since we know predicate adjectives and predicate nouns are diagrammed in the same fashion, the sentence The cat is my pet would look similar to Image C. The only difference is “my” which modifies “pet” would need to be placed beneath the word it modifies on a slanted line as shown in Image Ca. Since the overall format of the diagram does not change with the variations of the sentence, it is a beneficial grammar teaching tool. New elements can be added, and once a student recognizes the basic idea of a diagram, it is not difficult to bring in those new grammatical constructions (Vitto 51).

Since we know predicate adjectives and predicate nouns are diagrammed in the same fashion, the sentence The cat is my pet would look similar to Image C. The only difference is “my” which modifies “pet” would need to be placed beneath the word it modifies on a slanted line as shown in Image Ca. Since the overall format of the diagram does not change with the variations of the sentence, it is a beneficial grammar teaching tool. New elements can be added, and once a student recognizes the basic idea of a diagram, it is not difficult to bring in those new grammatical constructions (Vitto 51).

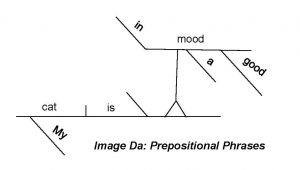

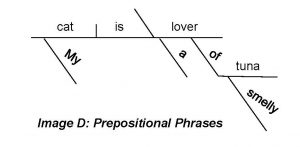

Notice how the predicate noun “lover” has both “a” and the prepositional phrase “of smelly tuna” beneath it. There is no limit to how many modifiers a word can have. While it may make for a complicated looking diagram, it is all correct. There are some situations where the predicate adjective is in the form of a prepositional phrase. In these cases, the phrase is put on a pedestal which floats above the main line as identified in Image Da with the sentence: My cat is in a good mood.

Notice how the predicate noun “lover” has both “a” and the prepositional phrase “of smelly tuna” beneath it. There is no limit to how many modifiers a word can have. While it may make for a complicated looking diagram, it is all correct. There are some situations where the predicate adjective is in the form of a prepositional phrase. In these cases, the phrase is put on a pedestal which floats above the main line as identified in Image Da with the sentence: My cat is in a good mood.