Benjamin Lucas Garcia is the Education Coordinator & PBS Teacher Ambassador for Southern Oregon Public Television. In 2017, SOPTV became one of five stations in rural areas across the U.S. to become part of the PBS Teacher Community Program, which seeks to connect local media arts educators.

Benjamin Lucas Garcia is the Education Coordinator & PBS Teacher Ambassador for Southern Oregon Public Television. In 2017, SOPTV became one of five stations in rural areas across the U.S. to become part of the PBS Teacher Community Program, which seeks to connect local media arts educators.

My world has been turned upside down. I’m now teaching a video class at North Medford High School as an industry instructor. It has put me back in a role that I once inhabited for six years.

Being the proclaimed “permanent teacher” in a classroom with 30 plus teenager students used to having substitutes changes the dynamics of a learning environment immensely. I quickly rediscovered that cooped-up students do what comes naturally to an improvising new teacher: test them. After the first class I looked in vain for an employee bathroom to cry in, but in all my trips to this school the previous year, I’d somehow never used one. I found a quiet place in the library, fought back my tears, and wrote two pages of questions any new teacher might think of, starting the list with “Teacher facilities?”

I’ve been working alongside teachers and students as a “Teacher Ambassador” the last 2.5 years. I was hired by NMHS a few weeks into the fall semester 2019. On my first day at the school, I was given keys, an employee handbook and sent to a classroom where none of the essential software worked — such as the attendance software. A teacher named Mike watched me start to introduce myself to students, a student interrupted asking if I was a substitute teacher, I backtracked to explain that I was the permanent teacher. Mike walked out of the classroom as I began my PBS Newshour Student Reporting Labs elevator pitch again, but it was interrupted again by another student wanting to know if he could use the bathroom. Then the side conversations started, then the phones came out, and by the time I was done with my 30 second spiel one of 31 students was paying attention to me. A day later, the IT guy and a front office lady began to help me gain access to crucial systems I needed to do my job. A week later, a vice principal had time to cram the orientation teachers get during “in-service” week into an hour. I began to feel better. Two weeks later, about two thirds of the students looked at me when I spoke. Three weeks later no one slept in class anymore.

“Teacher Ambassador” I wish I had one of those

Midway through the first semester I’m somewhat in the rhythm of solo teaching mode, but I occasionally find myself wishing I had my own PBS Teacher Ambassador to co-plan my lessons with, or to take the lead with advanced students during class so I can focus on the bottom of the to-do list tasks like: “differentiate for struggling learners in the class.”

Also it would be nice just to have someone to confide in when crazy things happen, which seem to happen daily, and they pile up contributing to a sense of “how isolated it can feel to be an educator” — especially when all the adults around you are too busy to listen. For example, the first week we undertook a class exercise where students wrote the most important news issue to them on sticky notes and posted their top three on a class poster. Privately, one kid shared his top three with me: “damn liberals,” “church bombings” and “mass shootings.”

After class, in a state of shock, I went to talk to an educator further up the chain of command about this. This person was busy with another student and so I said “It’s about one of your students; I can come back later; do you have availability after school?”

This person bluntly said, ”No.”

Then I asked, “Do you have availability any time this week or the next?’’

“Sorry I’m booked solid.”

And so lastly I said, “I’ll email you about it.”

“I’m so behind with those; it could be awhile.”

I had a follow up talk with the student myself, and our short chat convinced me that he is just fascinated by deeply controversial issues, which he emphatically and emotionally explained to me were “tragic and should be prevented by any means necessary.” I still emailed the educator I spoke with earlier.

The case of the adjustable table feet heist

In a few short months on the job, I can already tell a few more stories like the aforementioned — the case of the adjustable table feet heist, for example. One day we were setting up cameras and tripods, and to create more space in the classroom for 30 students to set up we stacked tables on top of each other. The tables stacked on top had their legs upright, and by the end of the “block” (period) five tiny adjustable feet were missing from the ends of the table legs. I didn’t notice until the tables were upright and the next teacher who uses the room pointed out that some of them weren’t quite level. The feet weren’t the only items to go missing in Term 1.

Anyhow, within the last month a very sweet teacher on special assignment, Bonnie, has been helping me figure out the grading software, and also a teacher friend, Jamie, with whom I’d participated in Coffee EDU meet-ups last year, stopped by my classroom to let me know she’s right around the corner and that the monthly meet-ups would be starting again soon. Both helped me understand how the gradebook works the day after mid quarter grades were due.

Recently, I met up with Tisha Richmond, who I co-planned and co-facilitated a teacher conference with last year, “Make Learning Magical!” She’s going to pop in to help me with a Google Classroom issue soon — ah, how good it feels that a teacher community is being felt so quickly in my new role. Teaching this one class underscores how important my media teacher support and mentorship work is. After I leave this classroom I very much look forward to the synergetic TCP work I do alongside hard-working media arts teachers at Hedrick and Central High. I hope these two teachers consider continuing their PBS Newshour Student Reporting Labs next school year, but for now I look forward to lightening their load and helping students learn the fundamentals of video production and journalism.

Where it all started

Shortly after the PBS Teacher Community Program (TCP) adventure began, April 2017, all five of us “Teacher Ambassadors” worked together to craft our individual elevator pitches for the educator support work we were embarking upon in rural areas where our TV stations are located: Iowa, North Dakota, Montana, Idaho and Southern Oregon:

As a Teacher Ambassador, I am the bridge between Southern Oregon Public Television (SOPTV) and local educators. I support our shared goal of improving learning outcomes for Southern Oregon’s students. From my experience teaching for the past six years, I know first-hand how isolated it can feel to be an educator. In SOPTV’s Teacher Ambassador role, I am working to address educator needs in our community in ways that are authentic and effective. My goal is to connect local educators with each other and with SOPTV, which is a resource for teachers to network, access peer-to-peer professional learning opportunities and enhance their teaching practice.

This message still rings true for my local support of educators, although I’ve since added the descriptor “media arts” before “educator” and “students”. The original mission was too broad for a one-person education program at our local station to tackle in a meaningful way, so my efforts are currently focused on supporting video teachers who are interested in piloting PBS Newshour Student Reporting Labs (SRL) sites. The NMHS video teacher stepped down, and they needed a video teacher, so I thought I’d pilot my own lab. I also have another SRL site up and running at Hedrick Middle School, which is going much better because we didn’t start late, and also we have industry standard equipment–oh, and having only nine students helps too. Lastly, there’s a possibility of a third site at Central Medford High starting the second term, but so far there is just one student signed up for it. Thus, at these two sites is probably where it will all end for this short lived SRL experiment as the Teacher Community Program grant runs its course June of 2020.

Follow

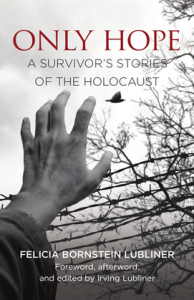

Follow Educator and musician Irv Lubliner of Ashland retired from Southern Oregon University in 2014 after teaching mathematics for forty years, working with every grade from kindergarten through graduate school. He recently edited and published his mother’s writing and oral presentation transcripts about her experiences living through the ghettos and concentration camps during the Holocaust.

Educator and musician Irv Lubliner of Ashland retired from Southern Oregon University in 2014 after teaching mathematics for forty years, working with every grade from kindergarten through graduate school. He recently edited and published his mother’s writing and oral presentation transcripts about her experiences living through the ghettos and concentration camps during the Holocaust.

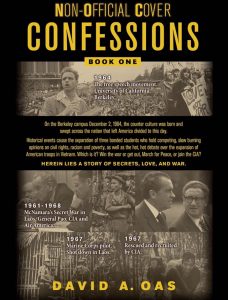

David A. Oas is Professor Emeritus of psychology at Southern Oregon University, having retired in 1997 to continue private practice as a clinical and forensic psychologist. In the 1970s he attended the University of Southern California Film School and wrote, produced and directed the film Raspberry Heaven now available as an Amazon Instant Video.

David A. Oas is Professor Emeritus of psychology at Southern Oregon University, having retired in 1997 to continue private practice as a clinical and forensic psychologist. In the 1970s he attended the University of Southern California Film School and wrote, produced and directed the film Raspberry Heaven now available as an Amazon Instant Video.

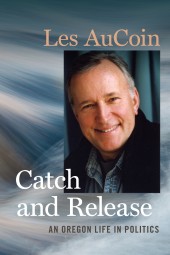

Les AuCoin was elected to the Oregon House of Representatives for two terms beginning in 1971 and was selected majority leader in 1973 at the age of thirty-one. He represented Oregon in the US House of Representatives for 18 years, from 1975 to 1993. The dean of the Oregon delegation and member of the House Appropriations Committee, he was described by the Oregonian as “the most powerful congressman in Oregon.” He helped create the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Forensics Laboratory in Ashland, the Seafood Consumer Research Center in Astoria, the Oregon Trail Center at Baker City, and the Lewis & Clark Visitors’ Center at Fort Clatsop. In 1992, he gave up his seat to run for the Senate.

Les AuCoin was elected to the Oregon House of Representatives for two terms beginning in 1971 and was selected majority leader in 1973 at the age of thirty-one. He represented Oregon in the US House of Representatives for 18 years, from 1975 to 1993. The dean of the Oregon delegation and member of the House Appropriations Committee, he was described by the Oregonian as “the most powerful congressman in Oregon.” He helped create the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Forensics Laboratory in Ashland, the Seafood Consumer Research Center in Astoria, the Oregon Trail Center at Baker City, and the Lewis & Clark Visitors’ Center at Fort Clatsop. In 1992, he gave up his seat to run for the Senate.