Alcestis, Proofiness, No Sleep Till Wonderland and Dirk Quigby’s Guide to the Afterlife

Alcestis

In Euripides’ Alcestis, the title character is the good wife, young King Admetus’ queen, who goes to hell in his place. Here’s the story: Admetus had won Alcestis’ hand with Apollo’s help but neglected to make the necessary offering to the goddess Artemis, who sends deadly snakes to the marriage bed. Helpful Apollo intervenes yet again and gets the fates to make a devil’s deal. When death comes for King Admetus, he’ll be spared if someone else offers to die instead. When the time comes, only Alcestis offers herself. Later Heracles, also a friend of Admetus, rescues Alcestis from death and returns her in disguise. Once Admetus realizes his shame, Alcestis true identity is revealed. Euripides tells it better that I do, but the classical version is pretty much all about Admetus and the Greek gods, with Alcestis (despite her title billing) merely being the object of desire and the embodiment of selflessness.

In Euripides’ Alcestis, the title character is the good wife, young King Admetus’ queen, who goes to hell in his place. Here’s the story: Admetus had won Alcestis’ hand with Apollo’s help but neglected to make the necessary offering to the goddess Artemis, who sends deadly snakes to the marriage bed. Helpful Apollo intervenes yet again and gets the fates to make a devil’s deal. When death comes for King Admetus, he’ll be spared if someone else offers to die instead. When the time comes, only Alcestis offers herself. Later Heracles, also a friend of Admetus, rescues Alcestis from death and returns her in disguise. Once Admetus realizes his shame, Alcestis true identity is revealed. Euripides tells it better that I do, but the classical version is pretty much all about Admetus and the Greek gods, with Alcestis (despite her title billing) merely being the object of desire and the embodiment of selflessness.

In Kate Buetner’s reimagining, the story is told from Alcestis’ point of view, including her reflections on life as a young princess, her sadness at her sister Hippothoe’s death, her anticipation of life with Admetus, her disappointment at his preference for Apollo’s company, and her ultimate practicality: she chooses to take Admetus’ place not out of selfless love but from the realization that her life as his widow would not be worth living. In the underworld, Alcestis hope to find her dead sister Hippothoe but is quickly swept up into the affairs of Hades and his queen Persephone. When Heracles arrives to the rescue, Alcestis would prefer to stay with Persephone. But she goes back.

Alcestis is of her time but her situation and her interior voice makes her an outsider as well. As outsiders to Greece ourselves, we resonate with her voice and her situation. Beutner’s novel also sparkles with the sounds, smells, and texture of ancient Greece and it is thick with the culture–the roles of the Gods, the dismissal of women, slaves and villagers, the casual crudity and cruelty of everyday–life from our perspective. She takes us to another world.

Proofiness

Proofiness, the mathematical sibling of Stephen Colbert’s “truthiness,” is about how people use numbers to deceive us. The fallacy that numbers don’t lie is almost so common as to be taken for granted, but it’s still fascinating (and shocking) to see how easily numbers lie. Author Charles Seife is a fine story-teller and excellent anecdote-selector he brings the unreliability of numbers to life with tales of skewed studies, meaningless polls, recounted elections (Bush-Gore, Franken-Coleman), gerrymander districts, gamed censuses, misled juries, misleading justices, and more. We see how different numerical fallacies—from Potemkin numbers to cherry picked data yield not just sloppy public policy but outright manipulation of the citizens.

Reading Proofiness, I came to have a larger worry, which Seife hints at but doesn’t dwell on. Proofiness arises because humans are pattern seekers. So we try find meaning (or find hope) in numbers even when the numbers are essentially meaningless or when they mean something else. Proofiness is about more than just deceptive mathematical story telling. It’s a design flaw in our humanity (because, presumably, finding patterns has an evolutionary advantage). So I could not help but thing of all the screeds against the humanities which attribute a supposed decline of culture to scholarship about the indeterminacy of linguistic meaning. (You know the arguments I’m sure, that relativist interpretation subverts objectivity and makes self-serving nihilists of us all.) But you have to wonder–perhaps the real culprit is not the indeterminacy of language but the indeterminacy of numbers. If the public doesn’t trust studies, polls, elections, or censuses, why should they take policy based in these seriously? After all, everyone knows the numbers are rigged.

I’m exaggerating, of course, to make the point that those who blame deception on the inadequacy of language are trying to shoot the messenger—what’s needed is a better understanding of how language, mathematics (and science too) are systematically misapplied and people like Seife who can talk intelligently about proofiness.

No Sleep till Wonderland

No Sleep till Wonderland brings back Paul Trembly’s narcoleptic detective Mark Genevich. It’s an oddly intriguing concept—reminiscent in some ways of Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn but also of Dennis Lehane in its portrayal of South Boston underclass trying to scrape by on petty crimes that get out of hand. The plot device of a detective with cataleptic blackouts mostly works. For me, the hard-boiled dialogue is most of the fun and the almost stream of consciousness is all the more gripping coming rapid-fire from a character who could fall asleep at any moment.

The narcolepsy itself is treated as more than a gimmick, and Genevich is a character often on the verge of memory, panic, and hopelessness. As Genevich says, “A narcoleptic is the ultimate cynic, left with nothing to believe in, least of all himself, because everything could simply be a dream, and a lousy, meaningless one at that.” The usual hardboiled sleuth is often a world weary outsider. In No Sleep Till Wonderland and his earlier The Little Sleep, Paul Tremblay takes world weariness to a new level.

Dirk Quigby’s Guide to the Afterlife

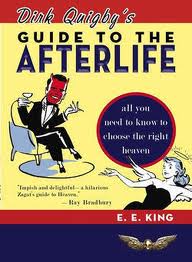

Dirk Quigby’s Guide to the Afterlife by E. E. King is both hard and easy to describe. Both Ray Bradbury and Margaret Cho call it “hilarious,” so I’ll go with that too. Quigby is an ad man who makes a deal with the devil—nothing new there. This deal however is to visit every religion’s heaven to drum up some business because, as Lucifer puts it, hell is too crowded. Dirk gets a sexy guardian angel with an electric personality, Angelica, and he is forever being whisked away to this or that afterlife through air conditioners, faucets, and other conduits.

Dirk Quigby’s Guide to the Afterlife by E. E. King is both hard and easy to describe. Both Ray Bradbury and Margaret Cho call it “hilarious,” so I’ll go with that too. Quigby is an ad man who makes a deal with the devil—nothing new there. This deal however is to visit every religion’s heaven to drum up some business because, as Lucifer puts it, hell is too crowded. Dirk gets a sexy guardian angel with an electric personality, Angelica, and he is forever being whisked away to this or that afterlife through air conditioners, faucets, and other conduits.

E. E. King does a nice job of explaining the various heavens, what to expect from the food, drink, accommodations, music, and so on, and how to get there. She give each the respect it is due, and uses italics for Dirk’s interior commentary (although sometimes I have to admit to being puzzled about whether the author is serious or kidding about some points of theology, which is more a comment of the religions than the exposition). And a lot of the writing is quite funny, and the characters are fleshed out enough to be engaging without taking over the book. In the end, all heaven breaks loose, but thankfully people have their Quigby’s.

And I learned some great Jeopardy! trivia too. Who was the only American woman to found a world religion? What two religions were founded in 1844?

(Answers: Mary Baker Eddy. And Baha’i and Seventh Day Adventists.)

Anderson’s forte is book reviewing, and he takes it seriously, as a genre of engaging criticism. In 2004 he won the Best Essay Award from The American Scholar, for an essay on James Joyce, and in 2007, the National Book Critics Circle awarded him the Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing.

Anderson’s forte is book reviewing, and he takes it seriously, as a genre of engaging criticism. In 2004 he won the Best Essay Award from The American Scholar, for an essay on James Joyce, and in 2007, the National Book Critics Circle awarded him the Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing.

Follow

Follow Everyone likes a good dystopia, from Wells and London to Zamyatin, Huxley, Orwell, Burgess and M. T. Anderson’s Feed. In Fast Eddie–King of the Bees, Robert Arellano takes us to the dystopic Boston of the near future, where a big-footed pickpocketing contortionist becomes the leader of underground Dig City.

Everyone likes a good dystopia, from Wells and London to Zamyatin, Huxley, Orwell, Burgess and M. T. Anderson’s Feed. In Fast Eddie–King of the Bees, Robert Arellano takes us to the dystopic Boston of the near future, where a big-footed pickpocketing contortionist becomes the leader of underground Dig City.  In Euripides’ Alcestis, the title character is the good wife, young King Admetus’ queen, who goes to hell in his place. Here’s the story: Admetus had won Alcestis’ hand with Apollo’s help but neglected to make the necessary offering to the goddess Artemis, who sends deadly snakes to the marriage bed. Helpful Apollo intervenes yet again and gets the fates to make a devil’s deal. When death comes for King Admetus, he’ll be spared if someone else offers to die instead. When the time comes, only Alcestis offers herself. Later Heracles, also a friend of Admetus, rescues Alcestis from death and returns her in disguise. Once Admetus realizes his shame, Alcestis true identity is revealed. Euripides tells it better that I do, but the classical version is pretty much all about Admetus and the Greek gods, with Alcestis (despite her title billing) merely being the object of desire and the embodiment of selflessness.

In Euripides’ Alcestis, the title character is the good wife, young King Admetus’ queen, who goes to hell in his place. Here’s the story: Admetus had won Alcestis’ hand with Apollo’s help but neglected to make the necessary offering to the goddess Artemis, who sends deadly snakes to the marriage bed. Helpful Apollo intervenes yet again and gets the fates to make a devil’s deal. When death comes for King Admetus, he’ll be spared if someone else offers to die instead. When the time comes, only Alcestis offers herself. Later Heracles, also a friend of Admetus, rescues Alcestis from death and returns her in disguise. Once Admetus realizes his shame, Alcestis true identity is revealed. Euripides tells it better that I do, but the classical version is pretty much all about Admetus and the Greek gods, with Alcestis (despite her title billing) merely being the object of desire and the embodiment of selflessness.  Dirk Quigby’s Guide to the Afterlife by E. E. King is both hard and easy to describe. Both Ray Bradbury and Margaret Cho call it “hilarious,” so I’ll go with that too. Quigby is an ad man who makes a deal with the devil—nothing new there. This deal however is to visit every religion’s heaven to drum up some business because, as Lucifer puts it, hell is too crowded. Dirk gets a sexy guardian angel with an electric personality, Angelica, and he is forever being whisked away to this or that afterlife through air conditioners, faucets, and other conduits.

Dirk Quigby’s Guide to the Afterlife by E. E. King is both hard and easy to describe. Both Ray Bradbury and Margaret Cho call it “hilarious,” so I’ll go with that too. Quigby is an ad man who makes a deal with the devil—nothing new there. This deal however is to visit every religion’s heaven to drum up some business because, as Lucifer puts it, hell is too crowded. Dirk gets a sexy guardian angel with an electric personality, Angelica, and he is forever being whisked away to this or that afterlife through air conditioners, faucets, and other conduits.