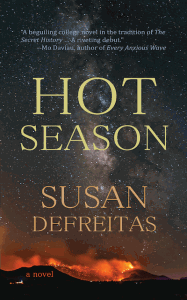

An author, editor, and educator, Susan DeFreitas’s creative work has appeared in The Utne Reader, Story Magazine, Southwestern American Literature, and Weber—The Contemporary West, along with more than twenty other journals and anthologies. She is the author of the novel Hot Season (Harvard Square Editions, 2016) and a contributor at Litreactor.com. She holds an MFA from Pacific University and lives in Portland, Oregon, where she serves as a collaborative editor with Indigo Editing & Publications.

You can learn more at susandefreitas.com

EB: I really enjoyed Hot Season. How did you come up with the idea for this particular story?

SD: In 2009, I moved from Prescott, Arizona, where I’d lived since 1995, to Portland, Oregon. There were a lot of reasons I left—to go back to school for my MFA, to pursue a career as a writer, and to explore life in a city—but in many ways it was a difficult decision. The Southwest, the high country of Arizona in particular, is close to my heart, and in many ways I dealt with the loss of that landscape and community by writing short stories set in Prescott—or, Crest Top, an anagram my friend and fellow author Christian Smith coined.

It didn’t surprise me that these stories wound up being linked, and as the work evolved, it turned into manuscript composed of three linked cycles, all set in my old neighborhood, the barrio. The first of these linked cycles was Hot Season, which I revised into a novel last year, at the behest of my publisher. I now plan to revise the next two sections of the larger manuscript into novels as well, creating a trilogy.

As for the actual content of Hot Season—it, like the next two novels, is based on real events in my life and in the life of my community. (Though it should be noted that none of the characters in the book are based on any one person, and I enjoy pulling from hearsay in my fiction as freely as I do the truth.)

EB: I appreciated the way that the work had several themes—coming of age, the appreciation of place, environmental issues. As a writer, how do you manage to balance those, without one aspect overpowering the others?

SD: Like Stephen King said, “The story is the boss.” As a writer, I’m fond of themes and aesthetics and atmosphere, but readers don’t care about such things unless they relate in a real and critical way to the emotional journey of the protagonist. Whenever I write, I usually start with the stuff most readers consider the window dressing and work down to the emotional substrate, the character arcs (pretty much the opposite of the way we’re taught). I know that I’ve reached what you term balance when all the parts of the story that my beta readers weren’t sure what to make of suddenly start to seem compelling for them. That’s how I know I’ve made that stuff matter to the reader—because they matter to the protagonist.

EB: You’ve got four protagonists: Katie, Jenna, Rell, and Michelle. As a writer, how did you give each one a distinct voice? And is there one that you identify with most strongly?

SD: I love that you consider them equal in terms of their role in this book because, again, these chapters started off as short stories—these people were their own protagonists, and they do all shift and change over the course of the book.

SD: I love that you consider them equal in terms of their role in this book because, again, these chapters started off as short stories—these people were their own protagonists, and they do all shift and change over the course of the book.

That said, I consider Rell the true protagonist of Hot Season—and though I (like every author) really am all of my characters, she is the one I most identify with. At a time when many young people are just trying to figure out how to cover the cost of keg, she’s trying to figure out the answer to Life, the Universe, and Everything, especially as it applies to the environmental crisis and where she’s going to go in terms of a career. That’s definitely who I was in my early twenties.

As for the voices, I think they come pretty naturally when you really know the characters—another benefit of working from the stuff of real life.

EB: Your character Dyson Lathe is loosely based a real-life activist Bill Rogers. How did you become acquainted with his story?

SD: Bill was a friend of mine. Most of my friends in Prescott knew him. Of course, we didn’t know he was one of the FBI’s Most Wanted—until the little community center he’d founded got raided. That event and his subsequent suicide in federal custody shook our community of activists and artists in a deep way. The shouts and rumors about the US government pursuing environmental activists under the antiterrorism laws established after 9/11 suddenly seemed a whole lot more real.

EB: Where do you see environmental literature as heading in the future?

SD: I think we’ll see “environmental literature” become less of a thing, along with another genre my book has found itself in, “political fiction.” In the years to come, I think any literature that seems truly relevant and current will incorporate environmental and political themes, even if it’s ostensibly about purely personal matters. It’s becoming more and more clear how these issues impact our lives at every level—and will impact the lives of the generations to come.

EB: The book opens with a bit of literal juggling, and I understand that you worked with a circus for a time. Tell us about that.

SD: I toured with something that called itself a circus—but was more along the lines of vaudeville—in my late teens and early twenties. There were many such roving bands of underground performers touring the country in those years (late Nineties and early Aughts), working in a range of styles. For instance, Circus Discordia was an anarchist crust punk fire and burlesque show that toured with a library housed in a giant green army tent; the Living Tarot put on New Age ritual performances in which performers embodied the Major Arcana, with an emphasis on improv (no two shows were the same).

There was a upswelling of really interesting, very grassroots performance art at that time, which I think was best documented by the book Freaks & Fire: The Underground Reinvention of Circus by Joe Hill.

As for my group, the Living Folklore Medicine Show, we were inspired by the early 20th century idea of the chautauqua, a traveling show that brought entertainment and culture to rural US communities, with speakers, teachers, musicians, entertainers, preachers and specialists of the day. My group was concerned about the environmental crisis, and we carried stories told to us by Native American elders in the Southwest and Southeast. There was an emphasis on storytelling, but also on the musical heritage of the US (we traveled with a pretty hot swing band) and on clowning, which served to bring levity to some heavy subject matter. I was both a storyteller and a clown; I occasionally played the banjo as well.

EB: What’s your life like now as a writer in Portland. I know you work as an editor and teacher and also write in various genres. You must be very busy.

SD: I am busy, it’s true. But I love not just writing but being a literary citizen, and editing and teaching are essential to that endeavor. It’s a real privilege to be part of an engaged, supportive literary community, which embodies the independent spirit of the Northwest.

EB: What are you currently working on?

SD: I’m working on a collection of speculative short stories entitled Dream Studies, one of which was recently published in Forest Avenue Press’s City of Weird anthology. In the New Year, I’ll also turn my attention to revising the next book in the Greene River trilogy, World’s Smallest Parade.

EB: Thanks for talking with us. Good luck with Hot Season.

SD: Thanks, Ed.

Follow

Follow