His works include Approaching Winter (Louisiana State University Press, 2015), Revertigo: An Off-Kilter Memoir (University of Wisconsin Press, 2014), The Wink of the Zenith: The Shaping of a Writer’s Life (University of Nebraska Press, 2008), A World of Light (University of Nebraska Press, 2005), In the Shadow of Memory (University of Nebraska Press, 2003), and Cream of Kohlrabi, Short Stories (Tupelo Press, 2011).

With his daughter Rebecca Skloot, he co-edited The Best American Science Writing 2011 (Ecco, 2011).

An Oregonian since 1984, Floyd moved from Portland to rural Amity when he married Beverly Hallberg in 1993. They lived in a cedar yurt in the middle of twenty acres of woods for 13 years before moving back to Portland.

We talked about his most recent book, The Phantom of Thomas Hardy (University of Wisconsin Press, 2016).

EB: How did you first get introduced to—and hooked on–Thomas Hardy?

FS: In 1968-69, as a college senior, I was led to Thomas Hardy’s novels by a teacher named Robert Russell who had become a beloved mentor, even a second father to me. “I have a feeling for Hardy,” he told me as we discussed possible topics for my honors thesis, “and I think you might too.” He was right, and the ways Hardy and Russell and I are tied together across the ensuing 48 years is an essential strand of my novel.

EB: This book started out as a vacation to visit gardens and writers’ homes in England a few years ago. What happened?

FS: Nothing unusual. My wife Beverly and I had included a two-night stay in Dorset as the final stop in our travels, an opportunity for me to pay homage to Hardy and to Russell, who had died at 86 just as we began planning our trip. While in Dorset visiting Hardy’s birthplace, home, grave, and various landmarks, I had no idea that I’d end up writing a book about it. We met no one connected to Hardy, spoke to no one about him. The visit was moving to me, and seemed like a time of closure in my relationships with Hardy and with Russell. Only once, in downtown Dorchester at the start of our Hardy wanderings, did I feel even the slightest sense of the writer’s presence, accompanied by a passing thought that it would have been sweet to somehow be able to call Russell from where I stood at #10 South Street, beside the heavy wooden door of a Barclays Bank that bore a round blue plaque saying “This house is reputed to have been lived in by the MAYOR OF CASTERBRIDGE in THOMAS HARDY’S story of that name written in 1885.” I felt that Russell would have gotten as big a kick as I did at the thought of an actual building being proclaimed as the home of a fictional character, making it a kind of gateway for our visit. And feeling that way led me to realize that my grief over his death was a big part of this journey. Only later, after we’d gotten home to Portland and I found myself drawn to re-reading various Hardy biographies, did I begin to see that building as a mystical spot linking Hardy’s real and imagined worlds, and to feel it beckoning me.

EB: You mention that Hardy ghostwrote his own biography, published under his wife’s name. Is your fictionalized memoir in a way a response to that?

FS: Yes. Hardy used the memoir form to concoct a self-ghostwritten biography designed to hide many of the deepest truths about himself , to present a dissembled or fictionalized self. In The Phantom of Thomas Hardy I used the memoir form to create a fiction meant to reveal the deepest truths about myself. I believed that, as with the four memoirs I previously published, I was on an essential journey of discovery and had to see and present the fullest truth or else I myself would be transformed into a lie. I didn’t want that to happen. Hardy did.

EB: The uncovering of memory—yours and Hardy’s—raised for me the question of what memories are at all, and the fuzzy border between memoir and biography and fiction. How do you see that literary landscape?

FS: I have always believed that when I wrote memoir, I was making a pact with the reader that said I would not make anything up. Everything in my memoirs would be the fullest truth I was capable of finding. That’s not what’s going on in fiction, even in fiction that presents itself in the form of memoir.

EB: I was struck by the way in which thinking about someone else’s life, makes us think about our own, and how you managed to make your life and Hardy’s illuminate one another. As you combined the two biographies, did you worry that you would trip over one another? Did it take a while to get it just so?

FS: No, I never felt that either Hardy or I would be lost in each other. He was and remains very Other. What did happen, after re-reading the eight Hardy biographies and various studies, some of the novels yet again and many of the poems, and after reading the absurd accounts of Hardy’s presumed secret love life, after going over my travel notes and photos and the materials gathered during our time in Dorset, I found myself feeling as though I understood Hardy more clearly. Understood where he was in terms of love and in terms of his writing about it. Began to see him as a character, as a person rather than as an iconic literary figure or as the clichéd doom-and-gloom-master.

EB: There is quite a bit of research in the book, along with the fiction. What did you learn that you didn’t know before?

FS: It was less a matter of learning things I hadn’t known before than a matter of coming to a fresher understanding. A matter of emphasis.

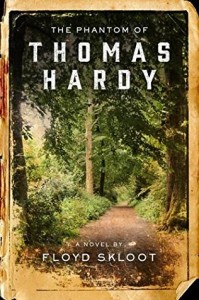

EB: I’m curious too about the cover and title, which has an interesting artistic effect giving the impression of fraying edges. How was that chosen?

EB: I’m curious too about the cover and title, which has an interesting artistic effect giving the impression of fraying edges. How was that chosen?

FS: The photo was taken by Beverly as we walked through the woods leading to Hardy’s birth home, the place where he grew up and where he wrote his first four novels, backed up to the landscape that dominated his imagination for life. So the reader enters the book at ground-zero, where Hardy entered the world. The cover design, including the fraying edges, was done by the marvelous design team at the U. of Wisconsin Press. It absolutely floored me–a perfect presentation, I believe. And, as a reader will discover, in absolute harmony with the plot of the novel.

EB: The title also struck me. Phantom seems like the right choice, as opposed to ghost. It presents a sense of something perhaps not really there as opposed to something haunting you. As a poet, did you spend much time thinking about that or settle right away on The Phantom of Thomas Hardy.

FS: The Phantom of Thomas Hardy was there as the book’s title from the get-go. Was the working title all the way through composition and three rounds of revision. At the suggestion of a reader concerned that people might not know or like Hardy, or might think it a scholarly book, I tried on an alternative title but didn’t feel comfortable with anything other than The Phantom of Thomas Hardy. I think that title refers not only to the presence of Hardy in Floyd’s story–a phantom perhaps of Floyd’s neurologically compromised thought process–but also to the various phantoms connected to Hardy himself. As one of the epigraphs–a quote from a Hardy love poem–says, “That her fond phantom lingers there/Is known only to me.”

EB: You’ve written now twenty books and move among poetry, essays, fiction, and memoir. Do you have a favorite form of expression? How do you decide the right genre for a particular topic? It does it decide for you?

FS: I don’t have a favorite genre to work in. But I think of myself as a poet first–that was how I began as a writer in the mid-1960s, and I feel that my prose work is informed by my poetry in terms of its compression, its language, its use of imagery. Eventually, my work in essays/memoir/fiction came to inform the poetry in terms of its use of scene and narrative, of character.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

Follow

Follow