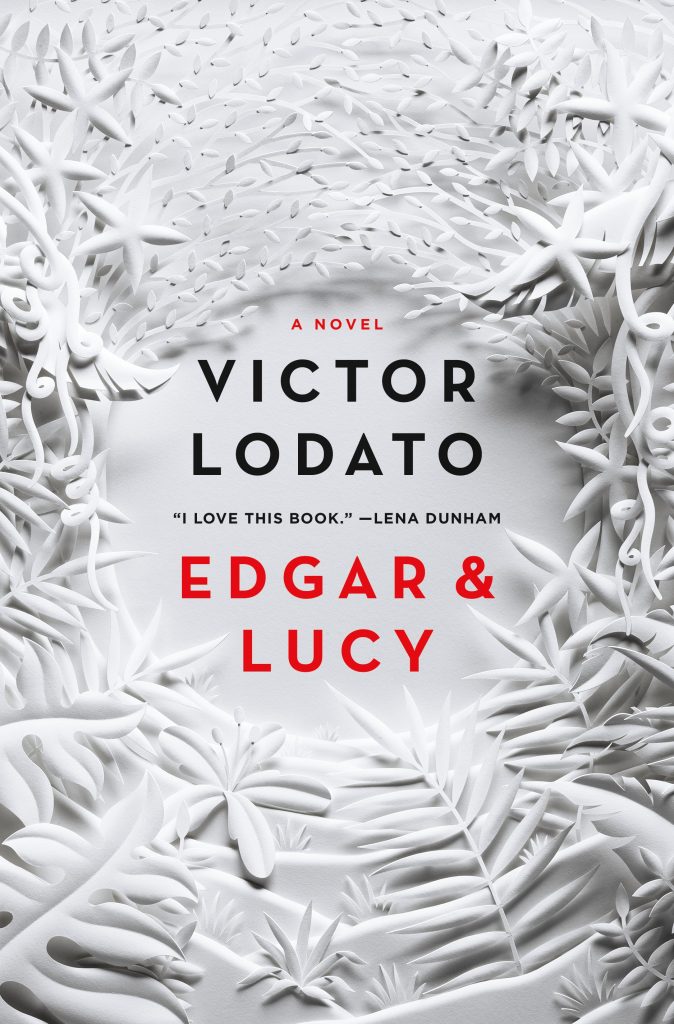

Victor Lodato is a novelist, playwright, and poet. His first novel, Mathilda Savitch, was called “a Salingeresque wonder” by The New York Times and was on the “Best Book” lists of The Christian Science Monitor, Booklist, and The Globe and Mail. Mathilda Savitch won the PEN USA Award for Fiction and the Barnes & Noble Discover Prize.

Victor Lodato is a novelist, playwright, and poet. His first novel, Mathilda Savitch, was called “a Salingeresque wonder” by The New York Times and was on the “Best Book” lists of The Christian Science Monitor, Booklist, and The Globe and Mail. Mathilda Savitch won the PEN USA Award for Fiction and the Barnes & Noble Discover Prize.

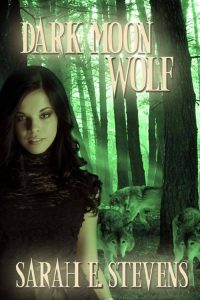

Victor’s second novel, Edgar and Lucy, was published this week (St. Martin’s Press). Lena Dunham calls Edgar and Lucy “profoundly spiritual and hilariously specific” and Sophie McManus lauds the “tender, funny, living immediacy of its characters.”

Victor is a Guggenheim Fellow and the recipient of fellowships from The National Endowment for the Arts, The Princess Grace Foundation, The Camargo Foundation in France, and The Bogliasco Foundation in Italy.

His work has been published in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Granta, and Best American Short Stories. A recent essay was published in the “Modern Love” column at The New York Times.

Originally from New Jersey, Victor lives in Ashland, Oregon and Tucson, Arizona.

EB: Tell us a little bit about your background. How did you find your way to writing?

VL: As a kid, growing up in New Jersey, in a working-class Italian-Polish family, I was the odd duck, writing poetry and melodramatic skits that I begged my older jock brother to perform with me. When I went to college (the first person in my family to do so), I entered a fine arts program, to study acting. After college, I was an actor for years. Often, though, I found myself being cast in plays that I didn’t really care for (for instance, a stint as Nicky the warlock in a revival of the 1950s Bell, Book, and Candle). Eventually, I decided to try my hand at writing some one-character plays for myself. Over a six-year period, I wrote and performed seven one-man plays, supported in part by a Solo Theater Artist Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. It was a busy and intense time, but, ultimately, I burned myself out. I’m basically an introvert, fairly shy, and after years of doing these shows, I realized that I felt much more myself when I was writing the pieces, rather than performing them. I stopped acting and became a playwright—and then, twelve or so years ago, I switched paths again. I wrote my first novel—Mathilda Savitch—which was published in 2009.

In regard to the multiple genres I’ve worked in, I used to feel that it was the moody, somewhat depressed Polish boy in me that wrote the poems, and then the more hot-blooded Italian boy that wrote the plays. But, in writing fiction, I feel like those two sides of me collaborate. Fiction seems to allow me to incorporate the various aspects of my nature into a single undertaking.

EB: I was really captivated by your first book, Mathilda Savitch, and by the wild combination of world-weariness and innocence that the title character brought to the narration. How did you capture such a voice?

VL: Mathilda’s voice just arrived in my head one morning with incredible force and clarity. And though the first words seemed a bit ominous (I want to be awful. I want to do awful things), I knew that they weren’t coming from someone evil, but rather from a child—a willful adolescent refusing to be contained. I really can’t begin any piece of writing without this deep connection to a voice. With Mathilda, I felt from the start that I knew her in my body, in my breath. Where such voices come from is one of the mysteries of the writing process, and one that I tend not to question.

EB: In some way that book seemed to be an allegory of the experience that young people—and all of us—had with terrorism. Is that part of what you had in mind?

VL: I started to write Mathilda Savitch in September of 2002, almost exactly one year after 9/11. The first few months of writing, I wasn’t thinking—at least not consciously—about terrorism or tragedy or grief. I didn’t know what the story was. I was simply following the voice of this young girl, who at that point was still a stranger to me. Over time, though, I began to see that Mathilda and I had a lot in common. Whereas I began the novel one year after 9/11, the story of the book begins one year after the death of Mathildaʼs beloved older sister, Helene. Terrorism hovers in the background of Mathildaʼs world, as well, and I can see now that by borrowing this child’s voice, I was able to address my own fear and confusion and sadness about 9/11 in a very open and innocent way. It was liberating to write in the voice of a child, from the perspective of someone who is still learning the world and interpreting its complexities for the first time. I think, in some ways, grief turns everyone into children: innocents standing before the incomprehensible.

EB: In Edgar and Lucy, your new novel, you tell the story of death and tragedy in an Italian-American family in New Jersey and young Edgar’s surreal path out of childhood. This seems to be a novel about what is real and true, and in which none of the characters are clear-cut. As a writer, you seem to be pushing us out of our comfort zone but holding our interest at the same time. What’s the key to that balance? For me it was in the small, familiar details of description.

EB: In Edgar and Lucy, your new novel, you tell the story of death and tragedy in an Italian-American family in New Jersey and young Edgar’s surreal path out of childhood. This seems to be a novel about what is real and true, and in which none of the characters are clear-cut. As a writer, you seem to be pushing us out of our comfort zone but holding our interest at the same time. What’s the key to that balance? For me it was in the small, familiar details of description.

VL: You always want there to be some kind of suspense in regard to what will happen next, or even in regard to understanding the motives or morality of the characters. I think at the core of all writing and reading is mystery—the ultimate mystery being, who are other people? One writes—and reads—in an attempt to answer this question, or at least to get closer to an answer.

Ultimately, I want to write stories that have transformative power—for the reader, for the characters, for myself. I guess I’m a romantic in that I want to read and write books that will change me, change my life. I like books that are grounded in emotional truth, but that can also feel mythic. Of course, I never think about myth at the front of my brain while writing. It’s more something I feel in my gut—a sort of physical sensation, a sense that this story is a matter of life and death. In Edgar and Lucy, the hero of the story is really Edgar. And his power isn’t physical strength or even overt bravery, but rather this sort of uncanny ability to love ferociously and to offer kindness in the most unlikely situations, and to offer it to people who don’t seem to deserve it. It’s funny, writing this book I realized how strangely rare real kindness is, when it’s the simplest thing in the world and should be so easy to offer. And I guess if I’ve woken up from a ten-year dream of writing this book into a world in which there is suddenly so much unkindness, then I feel good about putting this love story into the world at this particular moment. Because, ultimately, that’s how I see this book—as a love story. And not just one story, but a number of love stories that are all connected to each other. It took everything I had in me to write this book. I don’t take fiction writing lightly. I really do believe that fiction, both the writing of it and the reading of it, is a very civilizing thing. In it, there’s the possibility of learning to love people who are nothing like you—and that’s where the miracle of art happens, and you change.

EB: I wondered if the crispness of the characters in your novels—Edgar, Lucy, Mathilda—comes from your being a playwright. How do you see the two styles of writing as coming together in your work? Was it difficult to write a longer piece or did you find that freeing?

VL: Certainly, writing from voice and character is an extension of my work in the theater. When I write, I actively feel myself taking on the characters, performing them, really, while I work. I never write without talking to myself, without speaking the words out loud as I put them down.

I guess one could say that the medium of theater is fate, while the medium of fiction is memory. I try to bring into my fiction some of the danger of theater, to create narratives that, even as they describe the past, are somehow infused with a present-tense theatricality that raises the stakes of the emotional transactions.

One of the things that I love about writing novels is the freedom to let the story unfold over a greater length of time. In a play, the magic circle drawn around the characters has to be much tighter. When crafting a play, I invariably find that I write more scenes than I can actually use. In a play, too much extra material, too many diversions, can be fatal, especially if these things impede the sense of inevitability, the sense that we are witnessing characters caught in the wheels of fate. And while a novel’s power can be reduced by excess baggage, as well (and, in writing mine, I do think I apply my playwright’s habit of precision), the form is clearly a roomier one—one that allows the characters to have a few more detours of thought and situation. And, having fallen so deeply in love with Edgar and Lucy and Mathilda, I thoroughly enjoyed being able to give them a more generous life.

EB: I was struck by an early scene in the book where Edgar’s teacher is encouraging students to draw bananas and wine glasses, but Edgar wants to doodle instead. Does writing have a doodling aspect to it?

VL: I love this question. As Edgar says: drawing is when you have to make a picture of something that’s in front of you; doodling is when you just make stuff up. And writing, for me, is much more like doodling—at least in the beginning. I never work with a plan or an outline. For me, a first sentence is often like a crazy blob of paint that my subconscious throws down on the page—and then I work from there toward a greater understanding of the picture. Often, the first few paragraphs are a kind of free association—which I follow in an attempt to discover what’s really on my mind. I like to stay dumb as a writer, especially in the early stages of creating a story. I’ll trip myself up if I try to control things, or pretend that I know more that I really do.

EB: As a linguist, I feel compelled to ask about the names of your characters: Edgar and Lucy Fini, Mathilda and Helene Savitch. These are not your usual Ashleys and Michaels. What’s the role of characters’ names in fiction?

VL: To be honest, I usually just stick with the first name that pops into my head for a character. Only rarely do I question this impulse and change the name. Edgar was born to me as Edgar—the same for Lucy, the same for Mathilda. Even if a name seems a bit odd, I just go with it. And then of course sometimes the name leads me to understand more about the character later. When I landed on the name Edgar, it made me question who had given him this name—a question that ended up revealing some things to me about his father. Also, the name Edgar seemed sort of “gothic”—and maybe that encouraged me to lean into some of the more gothic elements of the story.

I do think, in many ways, that this book is a true gothic, in that it’s about Edgar and Lucy’s complicated connection to the past, and there’s definitely a sense of the past as a source of malignant influence. And of course all of this is happening in an updated version of the ruined castle, which is the dilapidated Fini house, certainly a haunted place. While working on this novel, I sometimes imagined a playful subtitle: Edgar and Lucy, A New Jersey Gothic—and this actually gave me permission to go with a more heightened kind of storytelling, and not to be afraid of the emotional temperature of the book—which gets pretty hot, at times. I was often sitting at my desk, shouting or laughing or crying. I can only imagine what my neighbors must think.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

VL: Thank you, Ed, for asking such good questions!

Follow

Follow