Kimberly Jensen is professor of History and Gender Studies at Western Oregon University where she teaches courses in United States history, the history of health, medicine and gender, and autobiography, biography and memoir in American history. Jensen has a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa and has published three books and several scholarly articles. Her latest book is Oregon’s Doctor to the World: Esther Pohl Lovejoy and a Life in Activism, published by the University of Washington Press. It’s the biography of the Oregon doctor who became a world-renowned public health activist and leader in medical relief efforts.

Kimberly Jensen is professor of History and Gender Studies at Western Oregon University where she teaches courses in United States history, the history of health, medicine and gender, and autobiography, biography and memoir in American history. Jensen has a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa and has published three books and several scholarly articles. Her latest book is Oregon’s Doctor to the World: Esther Pohl Lovejoy and a Life in Activism, published by the University of Washington Press. It’s the biography of the Oregon doctor who became a world-renowned public health activist and leader in medical relief efforts.

Kimberly Jensen is also the author of Mobilizing Minerva: American Women in the First World War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008) and, with Erika Kuhlman, co-editor of Women and Transnational Activism in Historical Perspective (Leiden: Republic of Letters, 2010).

We sat down to talk about Oregon’s Doctor to the World.

EB: I had not heard of Esther Pohl Lovejoy. But reading your book I see that she’s as important a figure as Jane Addams in Chicago. Could you tell our readers a little bit about her?

KJ: She was born in 1869 in the logging community of Seabeck, Washington Territory and moved with her family to Portland in 1882. A daughter of a laboring family, she worked her way through the University of Oregon Medical Department (now OHSU) by clerking in department stores and in 1894 was the second woman to graduate from the medical school. She was active in the Oregon woman suffrage movement and held appointed office as Portland’s city health officer from 1907 to 1909, the first woman to hold such a post in a major U.S. city. She helped to organize U.S. medical women for service in France in the First World War in 1917-1918 and found women doctors from other nations there who shared many of her experiences and concerns for women. As a result, Lovejoy was an organizer and the first president of the Medical Women’s International Association in 1919 to bring medical women together for effective action. She also chaired the international medical humanitarian relief organization the American Women’s Hospitals from 1919 until shortly before her death in 1967. The AWH was a precursor to groups like Doctors Without Borders but with a focus on supporting and empowering women. Both the MWIA and the AWH continue today. Lovejoy was the first woman in Oregon to campaign in a general election for U.S. Congress, in Oregon’s Third District in 1920. She was the author of four books, including the comprehensive history Women Doctors of the World published by MacMillan in 1957.

EB: How did you get interested in Lovejoy’s life and career?

KJ: My first book, Mobilizing Minerva: American Women in the First World War, addressed three groups of women – doctors, nurses, and women-at-arms – who claimed a more complete female citizenship through wartime service and who also challenged violence against women in wartime and in the institution of the military. Esther Lovejoy was a small but significant part of that study because of her medical work in France during the war and as a leader among women physicians. By the time I was completing that project I had moved to Oregon to teach, and I learned that Lovejoy’s papers had been donated to the Historical Collections & Archives at the Oregon Health & Science University not long before. I hoped that there might be enough material for a biography, for by that time I knew enough about her that I was eager to know more about what shaped her activism and what she did before and after the First World War. The strength of that collection at OHSU, combined with many other archival collections and significant coverage of her life and work in newspapers and medical journals, led me on a research and writing journey that culminated in her biography.

EB: Esther Pohl Lovejoy lived to be almost 100—she was born in 1869 and died in 1967—and she worked all over the world. What was involved in researching someone with such a long life and wide public impact?

KJ: It was definitely a long-term project. I needed to know about Lovejoy’s birthplace in the logging community of Seabeck, Washington Territory, about Portland from the 1890s to the 1920s, medical women’s history, the history of woman suffrage and women’s rights movements, medical humanitarian relief, transnational women’s activism, the First and Second World Wars, women office holders and candidates for office, women’s organizations, and international politics. Research is a process of discovery that, like any journey, requires advance preparation, travel, stamina, and sharing what one has learned. I traveled from archives in Oregon and Washington to Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and London and visited the Paris settlement house where she lived and worked during the First World War. Historians cannot make their journey without archivists who welcome us and suggest new leads and sources that we did not know existed. They even celebrate with us when we make those incredible discoveries. I did my work as historic newspapers began to be digitized, but I conducted much of it sitting in front of a microfilm reader finding the hidden treasures in the midst of pages and pages of other materials.

EB: What do you think shaped her views about health and social justice?

EB: What do you think shaped her views about health and social justice?

KJ: Lovejoy’s experiences as a physician and public health activist and city health officer in Portland demonstrated that health depended on access to health care, but also to education, a living wage, safe housing, clean milk and pure food, and freedom from violence. Poverty and inequality caused disease just as much as physical illness. She believed that the state and citizens were partners in creating civic health. This was the foundation for her work for votes for women because she knew that women needed the power of the vote to enact policies for healthy communities. When she was city health officer and the bubonic plague threatened Portland in 1907-1908 the male city council and business community did not hesitate to provide funding for prevention to save Portland’s economy. That worked and there were no cases of plague in Portland. But at the same time voteless women campaigning for pure milk in the city when children were dying (including her own son Freddie in 1908) could not get political leaders to act for change. This convinced her that women needed to be voters, office holders, and policy makers to shape healthy and just communities. Lovejoy worked with African American clubwomen in Portland and crossed other lines of class and ethnicity in her suffrage work. She continued this coalition building across groups in her work abroad. In her presidential address to the Medical Women’s International Association in 1922 she expanded the idea of civic health she had forged in her Portland years to embrace a program of international health. This she defined as the prevention of disease by ending war and social and economic inequalities across the globe. This was a big plan, but she believed that women were at the center of it and could achieve it by working together and for one another.

EB: You describe her as a believer in feminist, transnational organization and in constructive resistance. What was involved in those beliefs? Could you unpack them just a bit?

KJ: In 1926 a journalist described Lovejoy’s activism as constructive resistance and Lovejoy used this phrase to describe her work. She defined constructive resistance as the ability to take effective action against unjust power – working for votes for women, challenging city council members to take action to make Portland a safe and healthy city for all its residents, campaigning on a reform ticket for congress, supporting refugees through medical humanitarian relief, organizing women globally for international health and an end to war. She identified and resisted unjust power by taking constructive action. Her feminist transnational activism was based on the view that women working together above and across national boundaries could do things that nation states or international organizations could not do for women’s health, empowerment, and equality. And in turn that would make all communities safer and healthier and prevent conflict, war, and disease.

EB: The description of the election of 1920 was really interesting to me. Were the politics of that time just as contentious as today’s?

KJ: Oh yes! The 1920 election was the first national election after the World War. Supporters of progressive reform and peace grappled with conservative and reactionary groups who feared that activism by workers, women, and Americans of color to gain equality would unleash a socialist revolution in the United States. Lovejoy received the endorsement of the Democratic, Progressive, Labor, and Prohibition parties for her campaign for U.S. Congress in Oregon’s Third District that year. Her opponent was C.N. McArthur, the conservative Republican incumbent. Members of the Lovejoy for Congress Club emphasized that this was a battle between the people and corporate interests. They named McArthur a tool of those interests and an ineffective MAWSH (Might as Well Stay Home) member of congress in their campaign ads. The social media of their day included vivid newspaper advertisements, campaign cards by the tens of thousands, and banners and signs across the streets and in storefronts of the district. As the election approached Lovejoy was making six speeches a day to workers on their lunch hour, to women’s groups including African American clubwomen, and to other labor, civic, and political organizations. She had just published her first book, The House of the Good Neighbor, about her experiences in wartime France with a call for peace and transnational cooperation. Her opponents convinced some managers to remove it from shelves in local bookstores and department store displays, calling it Bolshevik propaganda. Lovejoy was a tireless campaigner who understood the importance of coalition building and popular media to win elections, something she had learned in her votes for women work. She garnered an impressive 44 percent of the vote when the election was generally a Republican landslide across the nation.

EB: Lovejoy gave a speech in called “woman’s big job.” What did she mean by that?

KJ: She gave the radio speech in 1928, the year that the United States and France signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact, or the Pact of Paris, that renounced the use of war to resolve conflict, an agreement eventually signed by fifty other nations. Lovejoy believed that women’s social and cultural experiences led them to value peace and health in their communities and across the globe. After the horrors of the First World War more women had achieved the vote and held political office, and they were now working to end war. She told her listeners: “the passion for permanent peace moving the world at the present time is due, in large measure, to the collective moral influence of women in politics . . . For ten years, in pulpits, women’s clubs, conferences, and elsewhere, the talking, writing, and general agitation necessary to produce the Pact of Paris has been going on in every city, town, and hamlet throughout the civilized world. Why work the churn after the butter has come?” (Oregon’s Doctor to the World, 190-91). She also maintained that in order to keep world peace women had a responsibility to use their civic power to maintain social justice – fostering healthy communities and an end to poverty, supporting education and equality.

EB: Was Lovejoy representative of women who came of age in the Progressive Era?

KJ: The Progressive Era was a time of many reform movements and a variety of challenges to the maturing industrial state and there was a tension between social reform and social control. So there were many strands of Progressivism. I think she was representative of many women who wanted to change their communities for the better and worked with others to make that happen. Knowing more about Lovejoy and her work contributes to placing Portland on the map as a key Progressive Era city. Lovejoy also took her local knowledge and experience to a transnational arena for public health after 1920, something that other women did for woman suffrage, labor, and health activism. If we only keep our focus on the United States, we miss this broader movement for progressive reform after the First World War.

EB: If she were alive today, what do you suppose she would be doing?

KJ: I think she would be working with a Non-Governmental Organization that empowers women to build coalitions to help one another achieve social justice and international health. Her goals have been adopted by many organizations including the United Nations Conferences on Women. When Lovejoy lost the 1920 Oregon congressional election she told supporters she would like to run for office again, but her transnational organizing took precedence thereafter. Perhaps she would consider a run for the White House if she were alive today.

EB: You teach memoir and autobiographical writing. What did you think of Lovejoy’s as a writer?

KJ: Lovejoy first developed her communication skills as a public speaker in the woman suffrage movement, as Portland city health officer, and as a congressional candidate. She learned to tell pithy and humorous stories to get the attention of her audience, to provide specific data to educate her listeners and convince them to act, and to stay on point and make her case quickly. She honed these skills in newspaper articles, letters to newspaper editors, interviews and reports. Then she moved to book-length histories and an unpublished autobiography. Her voice and style were remarkably constant across these different forms of expression. She used humor, memorable stories that championed the underdog, and irony to direct challenges to those in power and toward institutions and bureaucracies that limited women’s equality.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

KJ: You’re very welcome. Thank you for the invitation.

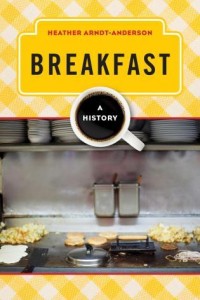

Portland-based Heather Arndt Anderson is the author of Breakfast: A History (Baltimore: Rowman & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy, 2013) and wrote the Pacific Northwest chapter in the 4-volume Food Cultures of the World Encyclopedia (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2011). Her recipes have been published in the cookbook One Big Table: 600 Recipes from the Nation’s Best Home Cooks, Farmers, Fishermen, Pit-Masters, and Chefs, and she is a contributing writer to the magazines The Farmer General and Remedy Quarterly.

Portland-based Heather Arndt Anderson is the author of Breakfast: A History (Baltimore: Rowman & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy, 2013) and wrote the Pacific Northwest chapter in the 4-volume Food Cultures of the World Encyclopedia (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2011). Her recipes have been published in the cookbook One Big Table: 600 Recipes from the Nation’s Best Home Cooks, Farmers, Fishermen, Pit-Masters, and Chefs, and she is a contributing writer to the magazines The Farmer General and Remedy Quarterly.  EB: What was the importance of the industrial revolution in changing the way we ate—and understood—breakfast?

EB: What was the importance of the industrial revolution in changing the way we ate—and understood—breakfast?

Follow

Follow