Marcie R. Rendon is the author of four mysteries featuring Cash Blackbear, an Ojibwe woman who defies the damaged protagonist stereotype. Cash is tough, slow to trust, and courageous, careful in everything she does. Cash hasn’t exactly come to terms with the shit the world’s thrown at her, but perhaps in part because of the shit, Cash Blackbear stands tall and strong in her everyday life. She’s conscious of her inside/outside status and uses it to advantage, but when it comes to crime, stands for justice and for Native people.

Marcie R. Rendon

Set in Northern Minnesota, Rendon’s writing is descriptive, lyrical, and compelling, drawing the reader into the physical, human and spiritual landscape. “I write what I know,” Rendon states, and she knows her subject well. Rendon explores bigotry, racism, and genocide as real in Cash Blackbear’s 1970s setting as these are today. The mystery format works perfectly for Rendon’s narrative style and is used to good effect, shining a powerful spotlight on social and cultural wrongs that Native people experience.

Murder on the Red River gives Cash and so Rendon, a platform to explore traumatized families and communities, torn by unexplained loss and the foster care system. Girl Gone Missing focuses on sex trafficking, the disappearance of Native women, and a legal system that turns a blind eye to abuse. And in Sinister Graves, evil in the guise of religion recalls generations of abduction, forced assimilation, and unmarked graves.

Maureen Flanagan Battistella: Your first Cash Blackbear mystery, Murder on the Red River, hit home on many fronts. Were you surprised at the success of your debut work?

MARCIE R. RENDON: Murder on the Red River received the Pinckley Debut Crime Novel Award for Women. I am kind of naive about some things; I didn’t know awards were a ‘thing’ so that was a very pleasant surprise and I believe set the book on the trajectory to be noticed. I always felt it was a good story, but it was five years of rejection before finding a publisher, so that was a lesson in determination. I think my women’s writing group was always more believing that it would ‘hit’ than I was.

MFB: Soho has picked up the series, which is major! How did that happen?

MARCIE R. RENDON: The first publisher of Murder on the Red River and Girl Gone Missing was Cinco Puntos Press. They sold their publishing company to Lee and Low Publishers, which focuses on children’s lit by folks of color. Cash Blackbear drinks beer and smokes cigarettes so I secured an agent (Jacqui Lipton) and she was the one who negotiated the series going to Soho Press. And they have published Sinister Graves and the most recent release, Broken Fields. We seem to be a good fit for each other.

MARCIE R. RENDON: The first publisher of Murder on the Red River and Girl Gone Missing was Cinco Puntos Press. They sold their publishing company to Lee and Low Publishers, which focuses on children’s lit by folks of color. Cash Blackbear drinks beer and smokes cigarettes so I secured an agent (Jacqui Lipton) and she was the one who negotiated the series going to Soho Press. And they have published Sinister Graves and the most recent release, Broken Fields. We seem to be a good fit for each other.

MFB: Where did Cash come from? Is she a mystic, a witch or something else entirely?

MARCIE R. RENDON: Cash is Ojibwe, from Northern Minnesota. Her superpower is being a Native woman. She is a composite of all the powerful and resilient Native women I know.

MFB: Why serial killers? You avoid gruesome but really get the point across.

MARCIE R. RENDON: I grew up rural and was always intrigued by the different crimes people in isolated areas could get away with. I think the Cash Blackbear series explores rural, isolated life and instead of the crimes remaining unsolved, she finds the culprit and brings justice for folks.

MFB: The places you write of are so familiar. I love how you describe the fields, the seasons, the sounds and smells. I can almost feel the mud, the chafe of wheat against my skin. It seems so natural to you.

MARCIE R. RENDON: Again, they tell you to ‘write what you know’ – and I know Minnesota and both the rural and reservation land of this part of the country. It is a beautiful and fulfilling spot on planet earth.

MFB: Who is your audience?

MARCIE R. RENDON: I write to create mirrors for Native people. We are so invisibilized in the landscape of North America and I want my people to be able to ‘see themselves’ and I want for ‘others’ to know that we still exist and to get to know us, know our worldview, and to know our resilience in the face of the historical oppression we have lived under and with.

MFB: You write of micro aggression so well, not just the act or the words but the feelings they provoke in your characters. You make me more aware of unconscious bias and cultural assumptions.

MARCIE R. RENDON: I am writing what I know, from my worldview. Truly, my initial goal is to write a good crime novel that those who read crime can pick up at 3 in the afternoon and not be able to put down until 3 in the morning. The created awareness in the reader is a side ‘win’.

MFB: I’m curious about white writers whose work features Indigenous people or Native customs and heritage. I’m thinking of Thomas Perry, Tony Hillerman, James Doss, William Kent Kruger for example. Is this cultural appropriation?

MARCIE R. RENDON: I think you have to ask them. I write from my lived experience and knowledge. I don’t have to research Native life or make Native friends to flesh out my writing. In this current period of time I contemplate writing a book about ‘other’ – like a blond, blue-eyed detective who rescues blond, blue-eyed women. (Less chance of being banned I think).

MFB: You use your crime fiction to address serious social issues. One of these is the theme of generational trauma which comes up often in your writing. It seems that the trauma can be just one generation or two, but also over many more years. Can you talk about what this is and how it can influence Native people today?

MARCIE R. RENDON: I am writing what I know. So many Native folks have told me, you wrote my story. I am honored that I have this opportunity to write our stories in ways that make it accessible to non-Native readers.

MFB: Cash seems most comfortable with Wheaton, but also with her bar buddies and work crew. Can you talk about what makes Cash feel comfortable, safe and what character development arc you are working towards in the series?

MARCIE R. RENDON: I am an untrained writer. Seriously, I have no idea what the arc of the series is. I write one book and by the end I have the crime for the next book and know that Cash will solve it. In that sense, I have been told that my books are character driven.

MFB: So what’s next for Cash Blackbear?

MARCIE R. RENDON: Broken Fields, book four was just released and I have started book five. No spoiler alerts.

Miigwech.

MARCIE R. RENDON

MARCIE R. RENDON is an enrolled member of the White Earth Nation. She was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters by Adler University and the McKnight Distinguished Artist award by the State of Minnesota, both in 2020. Murder on the Red River (Cinco Puntos Press, 2017 and re-issued by Soho Crime, 2022) was the 2018 winner of the Pinckley Women’s Debut Crime Novel Award and also a Western Writers of America Spur award finalist. Girl Gone Missing (Cinco Puntos Press, 2019 and re-issued by Soho Crime, 2021) was a 2020 Edgar Award Nominee for best novel in a series featuring a female protagonist. Sinister Graves (Soho Crime, 2022) was a Minnesota Book Award Finalist, Minnesota Public Radio News Best Book of 2022, Ms. Magazine Most Anticipated Book of 2022, Publishers Weekly Big Indie Book of Fall, and CrimeReads’ Most Anticipated Crime Book of Fall. Broken Fields, the 4th in the series was published in 2025. A standalone mystery, Where They Last Saw Her was published in 2024 by Bantam. This one features Quill, a woman who lives on the Red Pine reservation where she revives and renews strength through unity among the women of the community.

You can visit her website at: Marcie R. Rendon.

Follow

Follow

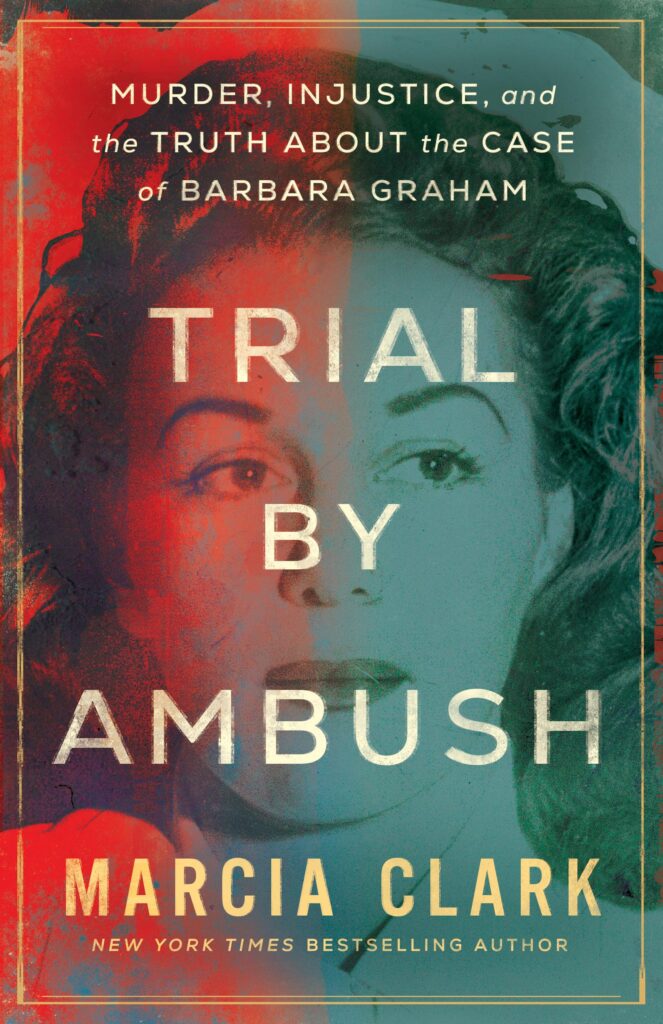

Read this one for my book club. It’s an intriguing true crime story ripped from the headlines of the 1950s. Clark is somewhat clunk as a writer–often interjecting herself into the story for no reason–but she’s done a fine job of researching the history of the Barbara Graham case and has a good eye for interesting historical details.

Read this one for my book club. It’s an intriguing true crime story ripped from the headlines of the 1950s. Clark is somewhat clunk as a writer–often interjecting herself into the story for no reason–but she’s done a fine job of researching the history of the Barbara Graham case and has a good eye for interesting historical details.