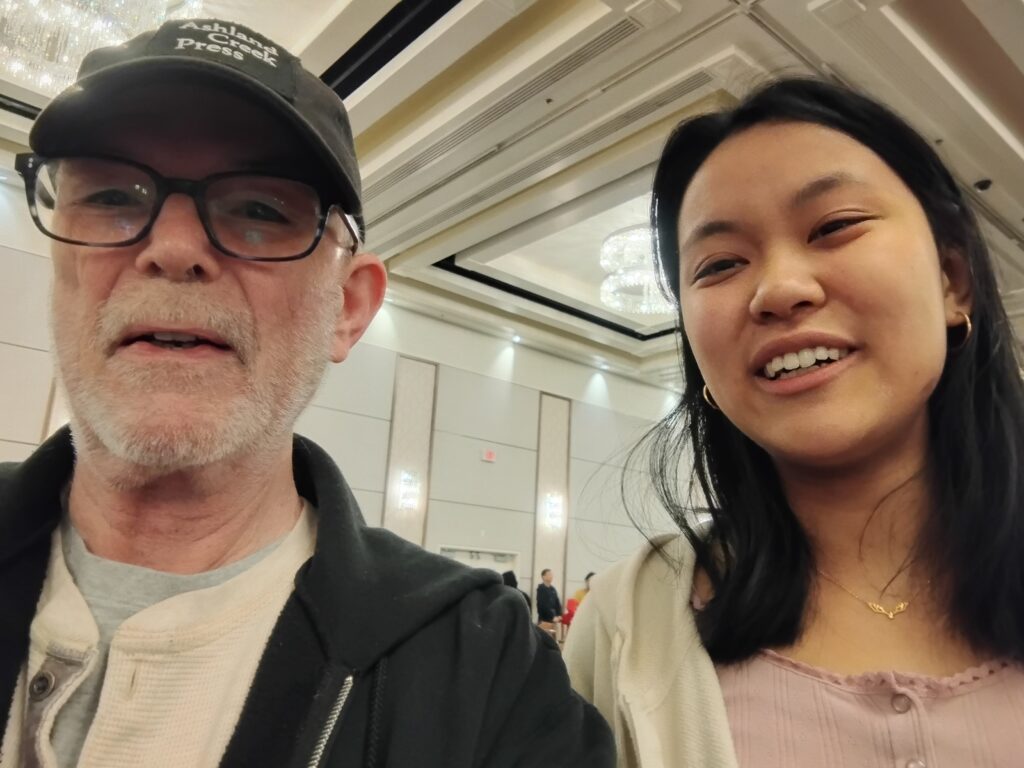

Parker Boom

Parker Boom graduated Summa Cum Laude from Southern Oregon University with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in Creative Writing. Among other things, she served as president of the Creative Writing Club and was selected to present her poetry at the Oregon House of Representatives. Her work has been published in The Hyacinth Review, Anodyne, and The Texas Review. Originally from the Central Valley of California, she will be entering study in a Master’s in Fine Arts program at the University of St. Andrew’s in Scotland.

Ed Battistella: Congratulations on your graduation from SOU.

Parker Boom: Thank you! It’s a little surreal. It was a long, deliberate effort toward graduating and it still happened more quickly than I could have expected.

EB: I understand that you were the student commencement speaker. Can you give our reader’s the 10-word version of your speech?

PB: Language belongs to us until it’s taken. Use it now.

EB: When did you decide you wanted to be a writer?

PB: Not until I was already in school. I was uncertain, and nervous, at first; I enjoyed writing but only knew it as a hobby. It was my first poetry class that truly decided it—it felt as if I had encountered something so beyond me it spoke to me as nothing else could. Language was peeled down to its DNA and then braided back together. It was exciting, intimidating, harrowing, fun; it made me want to run down every street. I began to see language as material, and how the way I shaped it (intellectually, structurally, phonetically, etc.) created certain and lasting resonances. I knew then there was no other thing for me.

EB: What sort of themes do you explore in your poetry?

PB: At the end of my first term at SOU I became slowly but seriously ill. By the end of my first year, I balanced classes, projects, and papers with emergency room visits and a half-dozen new doctors. For a long while it was an exhausting search for what was wrong with me, which seemed severe and unending. This became an exhausting search for simply a word, any diagnostic word, to contain it. I have never felt so keenly the controversy, the distance, between the language of something and the experience of it. I have ankylosing spondylitis, which is a form of autoimmune arthritis located in the spine. For a clearer picture, I like to describe it like this: if left untreated, my spine would fuse into one, long bone. It feels like that.

So, to answer the question: I often write about illness. Writing is occasionally useful to vent exhaustion and grief and pain, but writing only for that purpose is, to me, limiting. In my writing of illness, the intangible structure and materiality demonstrates the internal realities of an eternally sick person—a sculpture, in a sense, to reveal the relationships between the self, the body, and language. My work tends to focus on the experience of illness, the body as separate and inseparable from the self and the larger world, and pain, for which language fails, for which language is its only failing translator. This body-language-self dynamic extends, as it must, to other themes, like queerness, faith, and politics (though I hate to describe my work as political when literature is inherently political, and insistence on its depoliticization even more so). I want to explore broader themes in the future, such as nonlinearity, history, multimedia and digital literature.

EB: I listened to “Were Awe” the poem you presented at the Oregon State House of Representatives. How did that reading come about?

PB: I was approached by the Dean of Arts and Communication, Andrew Gay, about the opportunity, and he was the one who invited me to write a poem specifically for the occasion. Between his endorsement and the nomination of both of my Creative Writing professors, Craig Wright and Kasey Mohammad, I was chosen to read my work for SOU’s Lobby Day. I was honored to represent SOU as a young artist in higher education, and for the opportunity to speak to the House Representatives who are with us at this critical moment, who have some power to wield and the opportunity to wield it. That poem aims to be an evocative, nebulous reminder of something much larger than person or nation. It is happening right now—what are we mortals going to do about it?

EB: Who are some of your influences or writers you admire?

PB: There are too many to name, but I’ll try. For the heavyweight classics, I love Dickinson and Whitman. Then, Claudia Rankine, Lyn Hejinian, and Joan Didion, for more modern picks. Some contemporary poets who were integral to building my poetic sensibilities were sam sax, Omar Sakr, and George Abraham. All three use language to illuminate realities of identity and place. Anne Carson is brilliant. Her work is complex to the point of astonishing simplicity. Anne Boyer is arguably the most influential writer for me. Her work combines the personal, political, economic and medical in writings beyond genre and in a voice that is both distant and intimate.

EB: Do you have a favorite book?

PB: Forgive me, I have to choose more than one! In nonfiction: Anne Boyer’s The Undying. In fiction: Salman Rushdie’s The Ground Beneath Her Feet. In poetry: Anne Carson’s Plainwater.

EB: You are headed off to Scotland. How did you choose the program at St. Andrews?

PB: Anne Boyer teaches there! At SOU, we’re taught her collection Garments Against Women (which I almost included above, but figured I was breaking enough rules), and I connected with it immediately. St. Andrews is also a program that balances workshop with seminar. I appreciate this emphasis on our role as literary citizens—a major part of creating one’s own work is engaging with the work of others, past and present. I was accepted and waitlisted at other programs but chose St. Andrews to learn this way, with a writer I admire, in a completely new country. Moving across the entire length of California and then some (from San Diego to Ashland) was a major shift; now, I get the chance to do that tenfold.

EB: Thanks for talking with us. Best of luck going forward.

PB: Thank you for the chance to talk! I know wherever I go, Ashland will be with me.

Follow

Follow

Win by Harlan Coben

Win by Harlan Coben The Real-Town Murders by Adam Roberts

The Real-Town Murders by Adam Roberts