Sierra Adams is a senior at Southern Oregon University, where she studies English literature.

Sierra Adams is a senior at Southern Oregon University, where she studies English literature.

Authorship analysis is a branch of forensic linguistics that can be used to solve court cases as well as identify authors like JK Rowling and (possibly) Shakespeare. The term forensic linguistics was coined in 1968 by Jan Svartvik (Olsson). Forensic linguistics is a relatively new topic that has been used in some high-profile murder cases such as the 1996 case of Ted Kaczynski and more recently Chris Coleman in 2009. Authorship identification is an exciting new form of research that is used to identify authors based on linguistic analyses and computer programs. It can be useful outside of the courtroom as well. Recently, linguists have worked with computer programmers to develop software that can detect authorship, with a high-accuracy rating, within minutes. Because of the growing interest in forensic linguistics and specifically authorship identification some literary scholars have taken this opportunity to bring up the old argument of Shakespeare’s writing. Authorship identification techniques serve useful and interesting in all forms of written investigation.

Interest in linguistic authorship analyses can be traced back to the early 1700s, according to John Olsson, with some discussion over biblical passages in 1711 and Shakespeare studies in 1785. One of the first methods of forensic linguistics involved statistics and was invented by Augustus Morgan, an English mathematics professor, in 1851. However, it was not until the 1940s that authorship analyses using statistics and linguistic cues became a serious study (Olsson 12). With the new invention of powerful computers that could analyze statistics in the 1980s, computational linguistics arose and with it, more ways to analyze a text.

Tim Grant, a professor of forensic linguistics, writes that the study of authorship “attracts researchers and practitioners from a variety of disciplines including those working in linguistics, literature, history, theology, psychology, statistics, and computer science” (Grant 215). These researchers look for a variety of things when trying to understand or detect authorship. How the text was produced (medium, method, materials) is used to establish a basis of the work, especially if it was hand-written. The most important factor in authorship analysis is style (i.e. the use of pronouns or grammar cues such as semicolons, too many commas). Other telling features of writing include: tone, sentence structure, faux oversimplification or up-reaching (trying to sound uneducated vs trying to sound pedantic), and descriptions of people, places, emotions, or situations. Forensic linguists also dip into psycholinguistic profiling which means they try to determine the psychological background of the suspect and answer the question, ‘what kind of person wrote this?’ Lastly, they take a look at the texts relationship to comparison texts (Grant). These techniques allow for forensic linguists to scientifically organize and analyze data from personal writing and speaking.

One of the first high-profile court cases involving forensic linguistics was the case of Ted Kaczynski, or the Unabomber, who published a “rambling thirty-five-thousand-word declaration of the perpetrator’s philosophy” (Hitt). As the investigation progressed with little traceable evidence, the FBI turned to linguistics. They contacted a retired FBI agent and forensic linguist, James Fitzgerald, who used authorship analysis to determine who wrote the Unabomber’s Manifesto and,

By analyzing syntax, word choice, and other linguistic patterns, Fitzgerald narrowed down the range of possible authors and finally linked the manifesto to the writings of Ted Kaczynski, a reclusive former mathematician. Both Kaczynski and the Unabomber also showed a preference for dozens of unusual words and expressions…as well as the less familiar version of the cliché “You can’t eat your cake and have it too.” A judge ruled that the linguistic evidence was strong enough to prompt him to issue a search warrant for Kaczynski’s cabin in Montana; what was found there put him in prison for life. (Hitt)

This fascinating case brought a lot of recognition and interest to the field of forensic linguistics and authorship analysis. It also set the precedent for bringing linguists into the court to help sway the jury.

In 2009, Chris Coleman’s family was murdered after receiving several threatening “ransom notes” asking for money as well as emails threatening both Coleman’s family and his boss’s. No physical evidence connected him to the crime yet something about his story didn’t add up. Coleman was working as a security officer for a televised evangelical Christian company and was also having an affair. Beyond this, many of his wife’s friends testified against him in court. Forensic linguist Robert Leonard analyzed the ransom notes and Cole’s emails, journals, and notes and deduced that he was the killer himself, and even though “Leonard’s testimony was disputed in the courtroom…in a case with no physical evidence firmly linking Coleman to the crime, Leonard’s words—and Coleman’s—took on added weight.” (Hitt). This case, along with Kaczynski’s, put forensic linguistics in the courtroom and led to various classes and degree programs around the country (Butters) as well as made way for authorship analysis to be taken seriously as a form of investigation.

The tools of forensic linguistics and authorship analysis can be used in non-criminal cases as well, “today, computers can do this type of analysis in seconds, whether to uncover a case of murder-disguised-as-suicide, study an anonymous medieval poem, resolve disputes about authorial credit, or even provide political asylum for a refugee” (Juola). Patrick Juola developed a computer program that can detect authorship with over 90 percent accuracy. In 2013 J.K. Rowling published The Cuckoo’s Calling under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith. Juola’s software analyzed the novel and compared it to her other work. The software matched it within minutes. Juola writes,

Over the past decade, I have developed a computer program to do this sort of analysis of writing style, based on literally millions of different features. This program will take a sample of writing and determine, on the basis of similarity, who among a set of authors was most likely to have written that sample. (Olsson)

His computer program replaces hours of comparison work and helps build up linguistic evidence. An actual linguist would most likely have to double-check the work and be able to explain the differences and why they are significant. Even so, this is still an exciting development in the field of forensic linguistics. Not all, however, appreciate the results of computational authorship analyses.

Literary authorship analysis has been an area of interest since the 1700s and the question of Shakespeare’s authorship began around 1785 when “Reverend James Wilmot wrote that Sir Francis Bacon was the real author of the Shakespeare plays” (Olsson 11) and since then the Shakespeare Controversy has been fiercely debated. Over the years, curious fans of the famous plays have attempted to credit “Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, the 5th Earl of Rutland, the 6th Earl of Derby, and the 17th Earl of Oxford” (Dobson). The most convincing and/or popular competitor though, seems to be Christopher Marlowe who was a respected contemporary of William Shakespeare and who has a cult-like following that is just as passionate, if not as large, as the Bard himself. Organizations such as Shakespearean Authorship Trust are very active in the debate and even hold annual conferences to provide platforms for discussion. The founder of the organization runs a website called “Doubt About Will dot org” and signs his welcome letter, “Yours in doubt, Mark Rylance, Trustee of the Shakespearean Authorship Trust” (Rylance). In 2016 the Shakespeare Controversy made headlines after “The New Oxford Shakespeare edition of the playwright’s works — which will be published by Oxford University Press online ahead of a worldwide print release — lists Christopher Marlowe as Shakespeare’s co-author on the three “Henry VI” plays, parts 1, 2 and 3” (Shea). This shocking news was reported by the BBC, The New York Times, and The Washington Post among others. The Post reports that in order “to find out if collaboration occurred, 23 international scholars performed text analysis by scanning through Marlowe’s (and other contemporary writers’) works, creating computerized data sets of the words and phrases he would repeat, along with how he did so — all of the idiosyncrasies that comprise one’s writing” (Andrews). They found enough of Marlowe’s presence in the texts to credit him with co-authorship. Most Shakespearean scholars are not pleased with this controversy and have made themselves very clear on who is responsible for the Bard’s famous plays.

A particular favorite retort of mine comes from the 2008 edition of The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. This whopping 5.2 pound, 541 page encyclopedia is edited by Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells who are decidedly Stratfordians, or, pro-Shakespeare. Those who question the authorship of his plays are called anti-Stratfordians. In a biting entry under authorship controversy Dobson writes, “many commentators have paid reluctant tribute to the sheer determination and ingenuity which these anti-Stratfordian writers have displayed” (31) and later he goes on to write, “this Authorship Controversy, consciously or not, is very largely about class” (31) and since many of the anti-Stratfordians reside in the United States, Dobson claims that the USA is “a country whose citizens apparently find it easier to entertain romantic fantasies about their unacknowledged talents than do the British themselves” (31). Even though it was a little outdated it was definitely the most passionate and straightforward published response that I could find.

So, after reading this passage from 2008 and then discovering that the publishers at the very same Oxford University Press went ahead and included a co-authorship a mere eight years later, I had to find out how the editors of the encyclopedia responded. It turns out that the second edition of The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare was published in January of 2016 just before the computational authorship analytics that c-credited Marlowe were confirmed and published. In early November of 2016, the Oxford University Press released a statement by Gabriel Egan saying, “the news is that he collaborated as a writer much more than we used to think he did. We can now say with a high degree of certainty that upward of third of his plays were co-written in some sense or other” (Egan). As to how this was confirmed:

The new machine-based approach – Computational Stylistics – has started to reveal some very startling facts. For example, it is now clear that Shakespeare’s vocabulary – the total body of all the different words he knew – was not exceptionally large (as has long been assumed) but rather was just typical for the period. We now know that a lot of words and phrases that we used to think were coined by Shakespeare were already in use by other writers before him. Wherever his genius lay, it was not in his vocabulary, but in his ways of combining existing words and phrases. (Egan)

This piece seemed so defeated in tone that I began to feel genuinely sad for the self-proclaimed Stratfordians and their ardent belief in the singular-genius that was Shakespeare. I could not find any public responses from the original editors of the encyclopedia but I hope to one day read the updated entry on Authorship Controversy in the next edition. As far as Egan’s thoughts, ultimately he seemed to accept this unwelcome linguistic study by concluding, “we should apply this kind of scientific rigour as much to humanistic study as anything else, since no matter what their fields everyone who undertakes research for a living is ultimately in pursuit of the truth, and these are the best ways we have for finding it” (Egan). Regardless of co-authorship, Shakespeare is still a key figure in literature, history, and drama. The new techniques of authorship analysis may uncover even more shocking discoveries as it develops.

Authorship analysis, whether in the courtroom or in academics, remains a hot topic. This burgeoning branch of forensic linguistics will only get more valuable and more contested as time goes on. With most of us broadcasting our lives on social media, through texts, and online chatrooms, our writing can define us more than ever. How we present ourselves, what words we type, the pronouns we choose, and the slang we use, are all key pieces in creating our written and spoken identities. Now that forensic linguists can work with statistics and programmers to determine authorship from huge samples of personal writing, we will have to pay closer attention to what we are saying.

Works Cited

Andrews, Travis. “Big debate about Shakespeare finally settled by big data: Marlowe gets his due”, The Washington Post, October 25 2016.

Butters, Ronald. “Forensic Linguistics.” Journal of English Linguistics. Sage Publications, 2011.

Egan, Gabriel. “What did Shakespeare write?” Oxford University Press Online, November 8 2016.

Grant, Tim. “Approaching Questions in Forensic Authorship Analysis.” Dimensions of Forensic Linguistics, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2008.

Hitt, Jack. “Words on Trial; Can Linguists Solve Crimes that Stump the Police?” The New Yorker, July 25 2012.

Juola, Patrick. “How a Computer Program Helped Show J.K. Rowling write A Cuckoo’s Calling”, The Scientific American, 2013.

Marche, Stephan. “Wouldn’t It Be Cool If Shakespeare Wasn’t Shakespeare?” The New York Times, October 21, 2011.

Olsson, John. Forensic Linguistics. Continuum, 2004.

Rylance, Mark. The Shakespearean Authorship Trust, 2018. http://www.shakespeareanauthorshiptrust.org.uk/

Shea, Christopher. “New Oxford Shakespeare Edition Credits Christopher Marlowe as a Co-author” The New York Times, October 24 2016.

Ashland writer Morgan Hunt has written mystery novels, poetry, screenplays, short stories, and magazine articles, including Writer’s Digest. Her poems have been published in the California Quarterly, San Diego Mensan, and she’s considered one of the Oregon Poetic Voices. Hunt’s short story, “The Answer Box,” placed as a Finalist in the 2014 Saturday Evening Post Great American Fiction contest and in 2016 she published We the Peeps: A Political Caper and Wish Fulfillment.

Ashland writer Morgan Hunt has written mystery novels, poetry, screenplays, short stories, and magazine articles, including Writer’s Digest. Her poems have been published in the California Quarterly, San Diego Mensan, and she’s considered one of the Oregon Poetic Voices. Hunt’s short story, “The Answer Box,” placed as a Finalist in the 2014 Saturday Evening Post Great American Fiction contest and in 2016 she published We the Peeps: A Political Caper and Wish Fulfillment. MH: Neither Jefferson Graham nor Echo Sapien is based on a real person. Both are amalgams of my imagination, and a certain trait I may have encountered here and there. Jefferson Graham’s secret craving came about to foreshadow the theme of obsession. Most of us are obsessed with something – food, alcohol, drugs, relationships, religious fervor, politics. Inevitably that affects us. As for Echo, I do know a bit about the NSA because I was married to a Navy cryptologist who later worked as an NSA analyst. When we were married, I met enough of his social circle to absorb the type, I think. As a writer, one of the most delightful challenges of Bad Moon Rising was to see if, in the middle of a book, I could pivot from one sidekick-helper figure to another. And back again. I’ll leave it to readers as to whether I succeeded.

MH: Neither Jefferson Graham nor Echo Sapien is based on a real person. Both are amalgams of my imagination, and a certain trait I may have encountered here and there. Jefferson Graham’s secret craving came about to foreshadow the theme of obsession. Most of us are obsessed with something – food, alcohol, drugs, relationships, religious fervor, politics. Inevitably that affects us. As for Echo, I do know a bit about the NSA because I was married to a Navy cryptologist who later worked as an NSA analyst. When we were married, I met enough of his social circle to absorb the type, I think. As a writer, one of the most delightful challenges of Bad Moon Rising was to see if, in the middle of a book, I could pivot from one sidekick-helper figure to another. And back again. I’ll leave it to readers as to whether I succeeded.

Follow

Follow Sandra Scofield is the author of seven novels, including Beyond Deserving, a finalist for the National Book Award, and A Chance to See Egypt, winner of a Best Fiction Prize from the Texas Institute of Letters.

Sandra Scofield is the author of seven novels, including Beyond Deserving, a finalist for the National Book Award, and A Chance to See Egypt, winner of a Best Fiction Prize from the Texas Institute of Letters.  SS: This sounds counter intuitive but I stand by the assertion: Most writers don’t really know what their novel is about when they draft it. They have some kind of story idea and they have to pursue that to make it solid enough to carry the rest of the weight of a novel: theme, characters, motifs, etc. In revision you have to take a very intense look at what you’ve done so far in order to gain ground for rewriting. You have to be cool about it, self-critical, but also self-accepting and optimistic. The big question is: what is the story? Is it big enough for a novel? If you think the answer is yes, you begin to deconstruct the early work, seeking the best structure.

SS: This sounds counter intuitive but I stand by the assertion: Most writers don’t really know what their novel is about when they draft it. They have some kind of story idea and they have to pursue that to make it solid enough to carry the rest of the weight of a novel: theme, characters, motifs, etc. In revision you have to take a very intense look at what you’ve done so far in order to gain ground for rewriting. You have to be cool about it, self-critical, but also self-accepting and optimistic. The big question is: what is the story? Is it big enough for a novel? If you think the answer is yes, you begin to deconstruct the early work, seeking the best structure.

Sierra Adams is a senior at Southern Oregon University, where she studies English literature.

Sierra Adams is a senior at Southern Oregon University, where she studies English literature.

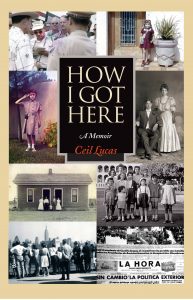

CL: See above. The effect was more powerful in Rome because I was in Italy during the Vietnam War and got the Italian/European perspective on it, for example, and on US politics in general. But in 1957, my civil engineer father was called to serve as a pallbearer at the funeral of the assassinated Guatemalan president [photo of my father with the casket in the book], in a situation that had totally been engineered by Eisenhower and the brothers Dulles. I was way too young in 1957, of course, to know what was going on, and my father passed before I was able to ask him all the questions I had. But when I went back and studied the history of Guatemala in those days, I was stunned. He was a civil engineer who did civil engineering in Guatemala, worked on irrigation projects, and he was also a fluent Spanish speaker, having been born and raised in New Mexico [he was born in 1909, before it became a state in 1912], but his company was a subcontract to the Dept of State run by John Foster Dulles [of the airport] and Dulles’ brother Allan ran the CIA. I came to find out that they were pretty much the puppeteers. I was ages 5 – 9, having a magical childhood in Guatemala. When I came back for college in 1969, I did NOT have a sense of myself as an American, not at all. I was “other”; Latin American, Italian, European. At 67, that sense of “I’m not from here” lingers, even after 46 years of living and working in the US. I started teaching Italian when I was a grad student, age 22, and am still teaching, not willing to give it up.

CL: See above. The effect was more powerful in Rome because I was in Italy during the Vietnam War and got the Italian/European perspective on it, for example, and on US politics in general. But in 1957, my civil engineer father was called to serve as a pallbearer at the funeral of the assassinated Guatemalan president [photo of my father with the casket in the book], in a situation that had totally been engineered by Eisenhower and the brothers Dulles. I was way too young in 1957, of course, to know what was going on, and my father passed before I was able to ask him all the questions I had. But when I went back and studied the history of Guatemala in those days, I was stunned. He was a civil engineer who did civil engineering in Guatemala, worked on irrigation projects, and he was also a fluent Spanish speaker, having been born and raised in New Mexico [he was born in 1909, before it became a state in 1912], but his company was a subcontract to the Dept of State run by John Foster Dulles [of the airport] and Dulles’ brother Allan ran the CIA. I came to find out that they were pretty much the puppeteers. I was ages 5 – 9, having a magical childhood in Guatemala. When I came back for college in 1969, I did NOT have a sense of myself as an American, not at all. I was “other”; Latin American, Italian, European. At 67, that sense of “I’m not from here” lingers, even after 46 years of living and working in the US. I started teaching Italian when I was a grad student, age 22, and am still teaching, not willing to give it up.