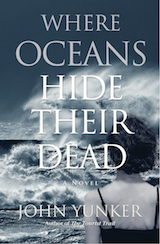

John Yunker is a writer of plays, short stories and novels focused on human/animal relationships. He is author of the novels The Tourist Trail and the sequel Where Oceans Hide Their Dead. He is also editor of the anthologies Writing for Animals and Among Animals.

John Yunker is a writer of plays, short stories and novels focused on human/animal relationships. He is author of the novels The Tourist Trail and the sequel Where Oceans Hide Their Dead. He is also editor of the anthologies Writing for Animals and Among Animals.

His full-length play Meat the Parents was a finalist at the Centre Stage New Play Festival (South Carolina) and semi-finalist in the AACT new play contest. Species of Least Concern was a finalist in the 2016 Mountain Playhouse Comedy Festival. His short play, Little Red House, was published in the literary journal Mason’s Road, and produced by the Studio Players Theatre in Lexington, Kentucky.

His short stories have been published by literary journals such as Phoebe, Qu, Flyway, and Antennae.

Yunker is also the co-founder of Ashland Creek Press, a publisher devoted to environmental and animal rights literature. He also has a passion for languages and for helping organizations develop better multilingual websites. You can find more of his work at JohnYunker.com

Ed Battistella: I enjoyed Where the Oceans Hide Their Dead. What prompted you to revisit the characters from The Tourist Trail.

John Yunker: I had a sense while writing The Tourist Trail that there was a bigger story to be told. And I too wanted to know what happened to Robert when he stepped off the plane in Namibia.

EB: One of the things that impressed me was the characterization and dialogue. You seemed to do a lot with a small ensemble of well-developed characters. I’m wondering how your work as a playwright influences your characterizations and your novelistic writing generally.

JY: I find that a character is “working” when you can hear him or her in your head and you become, in effect, the stenographer. This applies to playwriting as well. Of course, the trouble with having these characters talking inside your head is that they don’t always keep their mouths shut, which is another reason why there is a book two.

JY: I find that a character is “working” when you can hear him or her in your head and you become, in effect, the stenographer. This applies to playwriting as well. Of course, the trouble with having these characters talking inside your head is that they don’t always keep their mouths shut, which is another reason why there is a book two.

EB: The structure of the book, following three characters in different situations, was an interesting choice but it also required a sharp eye for details. How did you research the many convincing details, about seal hunting, espionage, chicken farming and more?

JY: Great question. Research, research and more research. Which includes everything from Wikipedia to Google Maps to following specific animal activists and court cases, as well as scientific journals and random news articles. I’d say the first few years of this book were more research and reading than writing. I’ve studied a number of well-documented cases of the FBI and animal activists, as well as trials. And I’ve gotten to know a few of the people who were imprisoned along the way; a few are still in prison as I write this.

EB: Are animal right groups routinely targeted as terrorist or tracked by private security? Where the Oceans Hide Their Dead painted a complex, fraught picture of activism.

JY: The FBI has targeted animal rights groups for decades now, but the risks for activists have become acute over the past decade. In 2006, the government passed the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, which effectively allowed the government to label anyone who simply disrupted the activities of a slaughterhouse or animal testing laboratory as a terrorist. In addition, many states now have “ag-gag” laws that have made it a crime to take photographs or videos within slaughterhouses or on ranches or farms – even if you’re taking a photograph from the side of the road. In addition to the FBI, corporations hire private firms to monitor and (in some cases) infiltrate these groups. And it’s not just animal rights but the health of the planet that is at stake. Being from St. Louis, I grew up not very far from Monsanto (which inspired a portion of the book). Most people don’t know that Monsanto once founded its own private town along the banks of the Mississippi specifically so it could avoid all regulation and freely do whatever it wanted with its chemical waste. The town is now called Sauget, and it includes a superfund site. But growing up there, I didn’t know any of this. I knew only that Monsanto was a very large company and that it had very tight security. I now know a great deal more about the company, as do a growing number of Americans.

EB: Have you got plans for a third book featuring Robert Porter and company?

JY: I do. Hopefully book three won’t take as long as book two, though I make no predictions.

EB: I was pleased to see Ashland and even SOU mentioned. Do you have connections with some of the other places you wrote about in the book?

JY: It’s difficult to keep my real life from seeping into my fictional life, so, yes, many of the locations are places I have a connection with. But not all. For instance, I’ve never been to Namibia and can only hope I did a decent job of portraying that region of the world; I hope to get there one day. Sadly, the seal slaughter along the shores of Namibia is all too true and still happening today. I did get to know, virtually, a man who rescued the stray seals who washed ashore in South Africa. The thing about people who devote their lives to rescuing animals – it can be such a heartbreaking and lonely life. This book, as well as the first, is my attempt to tell their stories.

EB: Thanks for talking with us!

JY: Thank you, Ed, for including me!

Follow

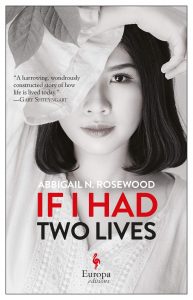

Follow Abbigail N. Rosewood was born in Vietnam, where she lived until the age of twelve. In 2012, she was the recipient of the Michael Baughman Fiction Award and the Outstanding Graduating Student in Creative Writing Award from Southern Oregon University. Her works have published in such literary journals as The Adirondack Review, Columbia Journal, Green Hills Literary Lantern, and The Missing Slate.

Abbigail N. Rosewood was born in Vietnam, where she lived until the age of twelve. In 2012, she was the recipient of the Michael Baughman Fiction Award and the Outstanding Graduating Student in Creative Writing Award from Southern Oregon University. Her works have published in such literary journals as The Adirondack Review, Columbia Journal, Green Hills Literary Lantern, and The Missing Slate.

AR: There are many successful literary works I admire that is only telling or showing. I try to balance both. In If I Had Two Lives, the protagonist’s way of expressing her feelings is often understated, which is essential to her character. Subtlety doesn’t work for everyone—I encountered a good amount of resistance from editors when my agent was trying to sell the book. Still, it is my firm belief that nothing can ever be subtle enough. Occasionally, however, it is useful to be exact, to give readers emotional anchors or affirmations of what they already know.

AR: There are many successful literary works I admire that is only telling or showing. I try to balance both. In If I Had Two Lives, the protagonist’s way of expressing her feelings is often understated, which is essential to her character. Subtlety doesn’t work for everyone—I encountered a good amount of resistance from editors when my agent was trying to sell the book. Still, it is my firm belief that nothing can ever be subtle enough. Occasionally, however, it is useful to be exact, to give readers emotional anchors or affirmations of what they already know.

Martha Darr is a poet and literary translator with advanced degrees in the Humanities. Her educational focus on African Diaspora Studies garnered funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and Fulbright Hays faculty grants. She has taught courses in Oral Literature, Language and Identity, and African/Latin American Studies. Some of her work has appeared in FIYAH, Exterminating Angel Press, Journal of American Folklore, and the bilingual anthology Knocking On The Door of The White House: Latina and Latino Poets in Washington, D.C.

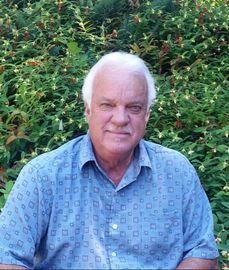

Martha Darr is a poet and literary translator with advanced degrees in the Humanities. Her educational focus on African Diaspora Studies garnered funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and Fulbright Hays faculty grants. She has taught courses in Oral Literature, Language and Identity, and African/Latin American Studies. Some of her work has appeared in FIYAH, Exterminating Angel Press, Journal of American Folklore, and the bilingual anthology Knocking On The Door of The White House: Latina and Latino Poets in Washington, D.C. Tim Applegate is the author of three poetry collections–At the End of Day (Traprock Books), Drydock (Blue Cubicle Press), and Blueprints (Turnstone Books of Oregon).

Tim Applegate is the author of three poetry collections–At the End of Day (Traprock Books), Drydock (Blue Cubicle Press), and Blueprints (Turnstone Books of Oregon).