Chris Scofeld is a writer, teacher, world traveler, and cellist living in Eugene, Oregon, with her husband and two goldfish. She is a former special education, art, and preschool teacher who grew up in Portland and has lived in Cambridge, MA, and Puerto Angel, Oaxaca (Mexico).

Chris Scofeld is a writer, teacher, world traveler, and cellist living in Eugene, Oregon, with her husband and two goldfish. She is a former special education, art, and preschool teacher who grew up in Portland and has lived in Cambridge, MA, and Puerto Angel, Oaxaca (Mexico).

Chris Scofeld has worked with Ursula K. Le Guin and Tom Spanbauer and she writes Young Adult, Literary and Adult Fiction. Scolfeld is being recognized this October by the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association as one of ten new Northwest novelists. You can visit her website at http://chrisscofieldauthor.com/

Chris Scofeld will read at the Schneider Museum of Art in Ashland on October 8 at 7 pm and at Tsunami Books in Eugene in November (together with authors Melissa Hart and Miriam Gershow). She will also be featured on a panel on young adult novels and identity at Wordstock this year.

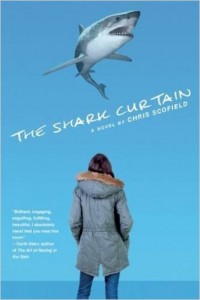

We sat down to talk about her debut novel, The Shark Curtain, which features a startlingly original hero–Lily Asher.

EB: I just finished The Shark Curtain and really enjoyed the book. How did this story–and this novel– come about?

CS: Thanks, I’m pleased you liked it. I worked on SHARK, on and off, for years; I wrote short stories and started other novels when I wasn’t working on it . . . How did it come about? Inspiration, for me anyway, is two-thirds daydream, one-third memoir. After a while, your stories have lives of their own and SHARK was particularly tenacious. As for its heroine Lily, I’ve known her for so long time now, I don’t remember how we met.

EB: Lily Asher has an active imagination. Is that they key to surviving adolescence—or life for that matter?

CS: Lily has a hyperactive imagination but something else is going on too. Something bigger than her, something possibly “supernatural” for lack of a better word. In the past her visions and behaviors might have labeled her as possessed or even a witch. These days, she’d more likely be labeled autistic or schizophrenic.

Lily lives in and out of her skin. Throw adolescence into the mix, and it’s even more difficult to predict what she’ll do next. Despite her love for her family, her growing desire to be accepted at “the watering hole,” and her need to be free of the visions and behaviors that isolate her as much as give her comfort, Lily knows how painfully different she is. Thankfully she’s an artist and her art (stories, illustrations, shoeboxes) is a tool, a conduit, a way to hold on to her sanity as well as her uniqueness. While the end of the book is hopeful, it’s also troubling—she realizes she will always be an outsider and it’s clear the visions will do what they damn well want with her. She thinks she’s finally run off SOG (Son of God) but what about the writing on her frosty window? What happens when you’re ready to cut the crazy lose, but the crazy isn’t done with you yet? There’s lots going on in The Shark Curtain. I hope the readers will see beyond a weird kid acting weird.

EB: Are there autobiographical elements here? Are you Lily Asher?

CS: SHARK is as close as I’ll get to writing a memoir.

EB: You’ve set the story in the 1960s. I’m curious about that choice…

CS: I was 17 when I graduated from high school in 1969, so I know what the culture was for a teenager back then. I also thought setting Lily’s intimate struggles against such a big canvas of change, gave The Shark Curtain more depth. Lily struggles to be honest with herself and her family, just as the demonstrators and the disenfranchised struggled for truth and transparency in the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War.

EB: Can you tell our readers a bit about the title?

CS: It’s a metaphor that runs throughout the book. The reader is introduced to it in the first chapter when Lily watches scuba diver Mike Nelson (the fictional hero of the popular 50s-60s TV show “Sea Hunt”) confront a shark under water. The “shark curtain” is where the blurred water (along with its possible danger) finally becomes clear. It’s where the unknown and reality meet, where reality finally asserts itself.

CS: It’s a metaphor that runs throughout the book. The reader is introduced to it in the first chapter when Lily watches scuba diver Mike Nelson (the fictional hero of the popular 50s-60s TV show “Sea Hunt”) confront a shark under water. The “shark curtain” is where the blurred water (along with its possible danger) finally becomes clear. It’s where the unknown and reality meet, where reality finally asserts itself.

EB: I was a young adult in the 1960s so the period details were a particular fascination for me: Sea Hunt, The Name Game song, Hai Karate, My Favorite Martian, Bonanza, and much more…. How did you research all that?

CS: I didn’t research the details , I remembered most of them. I was a TV baby and spent a lot of time soaking it up—from Edie Adams to the 1968 Democratic Convention. Up until my adolescent pot consumption got in the way anyway. Of course, when I wasn’t absolutely sure about something I googled it. Even so, one of my editors early on found a mistake. Basically I trusted myself on most of it. Writing is all about learning to trust yourself. AND your unconscious.

EB: Why did you choose the young adult genre?

CS: I didn’t. My literary agent didn’t pitch it as YA either, it was my publisher’s idea. Akashic Books wanted The Shark Curtain but they wanted it for their YA Black Sheep catalog. Akashic, along with editor JL Powers, got me excited about YA.

I’m not a YA reader but I’m becoming one. There’s wild, rich, genre-stretching stuff being written for YA readers these days, by some very talented writers too—established YA writers as well as popular adult fiction writers like Neil Gaiman and Sherman Alexie. Of course YA isn’t new: Jules Verne, Robert Louis Stevenson, JR Tolkien even Ursula le Guin wrote for “mature youth” long before that.

There are also beautifully written YA novels with an international, social justice focus—fiction and nonfiction books about young people caught up in war or racism or poverty, books with heart that are realistic but hopeful. The book blog www.thepiratetree.com is a great resource for both YA and children’s books like that.

My novel The Shark Curtain is considered YA-Crossover but the majority of my readers, and those attending my readings, are adults. That’s GREAT of course but I’d love to get teenage feedback on SHARK too.

EB: I’m an adult, more or less, but The Shark Curtain took me back. Did you also have adult readers in mind?

CS: Absolutely. Not only because it’s set in the 60s, but because of some of the questions SHARK poses. I don’t understand why some books with younger narrators are considered adult while others aren’t. Why were Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time both marketed as adult fiction and The Shark Curtain wasn’t? All three books have teenage narrators and the stories are told in first person. All three books deal with serious matters—death, family, forgiveness, identity.

Of course those distinctions are made by people who know the business better than me.

EB: What’s next for you?

CS: It was suggested that I write (another) YA novel, which I am. It’s very different from SHARK. I’ve also been making notes on a contemporary western (adult) ghost story I started a while back. I’d like to finish an (adult) murder mystery I started too. All three projects—the new YA novel, the ghost story and the mystery are fun departures from being inside Lily’s head. I’ve never attempted a ghost story or mystery before—it’ll be a challenge to see if I can pull them off!

EB: You also are a short story writer. What the difference for you between novel writing and short story writing? Does one have certain advantages over the other?

CS: Big questions. Most of my short stories average between 15-23 pages so they’re not very short, and the longer ones are still in progress so, again, “short” is a relative term. I always write more than I need (backgrounds of characters etc) so novels are probably my natural strength. My Dangerous Writer mentor Tom Spanbauer once said to me, “I bet you’ve never had writers block have you? “ No, I never have. Knock on wood—writing is a mysterious compulsion and I don’t want to queer anything.

As a reader I love the focus of a short story, the way the author drop-kicks you into another world where every word and action counts, yet you don’t necessarily know what’s going on. If it’s well-written you’re quickly sucked in, you believe, you’re transported. Writing a short story is like being inside a stretched skin, a drum maybe. The walls are right there, there’s only so far you can go, but there’s so much music between here and there. Know what I mean? It’s all about control.

A touching, well-crafted short story is a beautiful thing. But then so is a touching well-crafted novel. They’re just different animals.

EB: What are you reading right now?

CS: I hope to start either The Buried Giant by Kazuo Isaguro, or The Book of Strange New Things, by Michael Faber tonight. New novels by two of my favorite writers. Lucky me!

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

CS: Thank YOU.

Follow

Follow