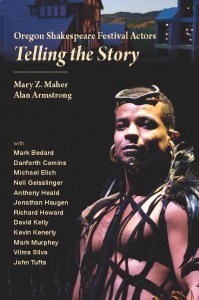

In their just-released book Oregon Shakespeare Festival Actors: Telling the Story, Mary Z. Maher and Alan Armstrong interview a baker’s dozen Oregon Shakespeare Festival actors talking about their process and telling some behind the scene stories as well.

In their just-released book Oregon Shakespeare Festival Actors: Telling the Story, Mary Z. Maher and Alan Armstrong interview a baker’s dozen Oregon Shakespeare Festival actors talking about their process and telling some behind the scene stories as well.

Mary Z. Maher has a PhD in Performance Studies from the University of Michigan, and is professor emerita at the University of Arizona in Tucson. She has written Modern Hamlets and Their Soliloquies on an AAUW fellowship, Actor Nicholas Pennell: Risking Enchantment at a residency at the Centro Studi Liguri in Italy, and Actors Talk About Shakespeare (Limelight/Applause Books). She was in the NEH seminars directed by Bernard Beckerman and Michael Goldman at the Folger Shakespeare Library and was a researcher on the Time/Life BBC’s The Shakespeare Plays series. Maher has interviewed Kevin Kline, Kenneth Branagh, Derek Jacobi, Stacy Keach, Zoe Caldwell, Martha Henry, Ben Kingsley and Simon Russell Beale, among others.

Alan Armstrong has PhD in Renaissance literature from Cornell University and served as Director of Shakespeare Studies at Southern Oregon University from 1986 until 2008. He has also been a senior scholar for the National Endowment for the Humanities national institutes for college professors at the American Shakespeare Center in Virginia and Shakespeare’s Globe Theater in London, dramaturg for seven Oregon Shakespeare Festival productions and co-editor of the journal Literature and History.

Oregon Shakespeare Festival Actors: Telling the Story is available from Wellstone Press.

EB: How did you come up with the idea this book and why did you call it Oregon Shakespeare Festival Actors: Telling the Story?

AA: Mary has done a couple of interview-based books, and once she retired to Ashland, it was natural to think about one on OSF actors. Conversations with actors had always been an essential part of the Shakespeare Studies programs I directed at SOU, and I had published interviews with Dan Donohue and Robin Goodrin Nordli. We kicked the idea around for years before the right moment—when we both had time to pursue the project—finally came. The main driver of the project, of course, was the fact that we have an extraordinarily large and talented company of actors here in Ashland, some of the best in the country. They deserve more recognition.

MM: My philosophy about titles is that they should be straightforward and should duplicate the inquiry that is going on in the mind of a Googler or an Amazon searcher: “Okay, I want a book where actors are talking about performing Shakespeare.” How about Actors Talk About Shakespeare (the title of my third book). There. You got it. Done. Actors say frequently, “My job is to tell the story.” So the actor’s goal in life can be found in the title of our book. I submitted several ideas and Alan arranged them into one neat and comprehensive title, Oregon Shakespeare Festival Actors: Telling the Story.

EB: How did you pick the actors to focus on? It must have been difficult to choose?

MM: One would think so, but it wasn’t. We’d both flirted with this book idea, and when push came to shove, we decided to meet for coffee on the Starbucks on campus, and each was to bring a list of a dozen actors. It was astonishing how close we were. Even wilder was that we split the list in seconds, and both of us were happy with our choices. There are always a couple on your partner’s list that you were drooling to interview, but life being what it is–full of surprises–sometimes you stay jealous, and sometimes you say, “Whew. Glad I didn’t get that one.”

AA: Mary remarks in our introduction that choosing the actors was easy, in the sense that the lists we brought individually to that discussion overlapped so much that we could agree on a final list. But it was hard to settle on any list of a dozen actors, knowing that there were dozens of others we’d be just as eager to include. Practical considerations also narrowed the field. It made sense for me to interview actors I had worked with and known, in some cases for decades. We wanted a mix of veterans and new faces, and of different kinds of actors. Some of the actors we admire hadn’t been doing Shakespeare recently, or were leaving the company, or were busy with other projects. Any OSF playgoer who reads the book is likely to say, “Why isn’t X here, too? What were they thinking?” I would, too—but we couldn’t do a 600-page book. What we could do is make sure that at least twelve of those beloved actors are there, in print, forever.

EB: Who did you have in mind as the audiences for the book? OSF afficionados? Students training to be company actors? Theatre historians?

AA: All of the above. But playgoers were first in our minds. OSF has such a large and loyal and knowledgeable audience that we felt sure they would want to read a book like ours. The actors we interviewed are not just respected but loved; they have followers, who are eager to know more about their stories and their skills. At the same time, since conversations with actors have been part of my classes and symposia and NEH institutes here since the 1980s, I was very conscious of the book’s value for teachers and students—especially theatre arts students. The actors’ chapters are full of hard-earned, practical advice to those just beginning in the profession, about learning lines, building a character, handling Shakespeare’s verse, etc. And for me, the interviews are also an important contribution to theatre history. Theatre is still an ephemeral art. Any evidence that we can preserve of how theatre is made—especially the direct testimony of the actors at its heart—is priceless.

MM: This question answers itself once you have to write a book proposal. It is the premier question every writer needs to clarify at the outset of the project. Our book proposal lists as potential readers novice and wannabe actors, master actors, teachers of actors, Shakespeare buffs, retired teachers (of both theatre and literature), and those many dedicated patrons who visit the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Defining that audience also conveys a sense of the local-ness of this project. It might not sell well in New York, could pick up a few buyers at Utah Shakespeare Festival, but the truth is that our audience comes to us from the West Coast, the fans that frequent this festival. They’ve had favorite performances for years, and now that their children and their children’s children also visit the festival (or already live here and reap the benefits of fantastic artists like Michael Hume or David Kelly or Barry Kraft teaching at the high school and SOU), they are eager to hear from these gilded actors who strut and fret their hour upon the stage. The entire theater community benefits, and the actors benefit because there is now a documented career for a dozen of them, their own story told. Of course we as authors benefit—not just from the quality of the information these artists provide but from the imagination and breadth of experience they offer in the book.

EB: The interviews give a sense of just how hard the OSF actors work in preparing their roles. Were there some common themes that you identified in their process?

MM: Absolutely. We asked about training and early mentors and how each actor got the acting bug, which varies from actor to actor, something I’d noticed in my other books about Shakespeare in performance. Topics that came up regularly were how each actor handled memorizing the lines (which is vastly different if the play is by Shakespeare or by Schenkken); the amount of research done and what kinds–travel, books, film and TV-watching, seeing other actors’ versions played. Several reported on the three different performance spaces at the Festival and handling each one, also referencing directors, lighting, stage, and costume designers and valued colleagues. Most of the actors had a bias against miking the stages, a revealing dialogue, with facets I’d never thought through.

MM: Absolutely. We asked about training and early mentors and how each actor got the acting bug, which varies from actor to actor, something I’d noticed in my other books about Shakespeare in performance. Topics that came up regularly were how each actor handled memorizing the lines (which is vastly different if the play is by Shakespeare or by Schenkken); the amount of research done and what kinds–travel, books, film and TV-watching, seeing other actors’ versions played. Several reported on the three different performance spaces at the Festival and handling each one, also referencing directors, lighting, stage, and costume designers and valued colleagues. Most of the actors had a bias against miking the stages, a revealing dialogue, with facets I’d never thought through.

I hear lots of variety in these actors’ methods of preparing a role. This subject also has a time factor, e.g., what did the actor do in his/her earlier days; and how does s/he do it now. Role preparation depends on one’s perspective and ideas, and most importantly of all, on the playwright. Ours is a Shakespeare festival, one with a very high caliber of master actors at work with years of fruitful experience in performing classics. That is the foundation stone and true power of OSF. You don’t find this quality of acting talent across an entire cast or across the U.S.

Who could have imagined the tutorial power of Will Shakespeare? As I sat in The Cocoanuts for the fourth time this season, I couldn’t help thinking about three of our actors–Bedard, Kelly, and Tufts—as they dished up truly divine madness onstage, yet were propelled with a legacy of performing the King of Navarre and Launcelot Gobbo, Richard II and Benedick, Henry V and Puck!

AA: One common theme: there’s no single path, not just one right way, to become an accomplished actor. Each story is different, and even individual actors use all sorts of different techniques, depending on the role—whatever they can find in their toolbags to do the job. All our actors all talked about how they marked up scripts, researched a role, memorized lines, built a character, worked in the rehearsal room, spoke Shakespeare’s language, dealt with the physical demands of acting, met the vocal challenges of the Elizabethan Theatre. And on some of these points, they disagreed completely. Some actors like to have every line memorized when they walk into the first rehearsal; others don’t, because it constrains their choices. Some like to do a lot of external research for a role; others find that a distraction from the script.

All our actors talked about what it meant to be part of a repertory company, what made an ideal director, what kind of training young stage actors need (but increasingly don’t get), what opportunities when seized made all the difference to their careers.

EB: I understand there are some never-before-told behind-the-scenes moments. Can you share one or two?

AA: I’ll defer to Mary here.

MM: Once you accept that Ashland is a small town, you remember Shakespeare’s advice on this subject: “Open your ears; for which of you will stop the vent of hearing when loud Rumour speaks?” “If false or true, I know not.”

That’s telling my story and I’m sticking to it.

EB: Mary has done earlier books interviewing actors. How are the interviews in this book different from the usual question and answer format?

AA: We started out in the conventional way, with a loose set of questions (focused especially on actor process), which we expected to be part of the book. But the interviews themselves made us start doubting the wisdom of the traditional format. Each of us, independently, remarked that our questions actually seemed to interrupt the flow of the interviews and disrupt the actor’s train of thought—not always a straightforward track, but always an interesting and illuminating one. I mentioned one day that all that was really required of us, at this stage, was to turn on the tape recorder and let the actors’ words flow. That’s an exaggeration, of course, but Mary and I both learned as we went along not to worry about “getting through our list” of questions so much as turning to them as prompts when the vein ran dry. But that didn’t happen often. Somewhere in the midst of our interviewing I ran across Holly Hill’s Actors’ Lives, which prompted us to wonder whether we, too, couldn’t in some way sieve out the questions and keep only the answers. Eventually, that’s what we did, by crafting the interview material into chapters or essays in the actor’s voice. That required cutting and some re-arranging—nobody’s conversation is perfectly linear and thematically organized—but the result was something that expressed better than a Q&A format what actors actually had to tell us about how they do their jobs.

MM: I’ve never used the question-and-answer format in any of my books because that method never tells the full story.

I’ve interviewed a number of hallmark actors–Kevin Kline, Derek Jacobi, Ben Kingsley, Kenneth Branagh, Stacy Keach–but I’ve never felt that a book about the subject of performance was comparable to the kind of feature you see in The Sunday Times Magazine. For one thing, the language actors use when talking about process is esoteric and abstract and often needs clarification for a reader who likes to explore this subject. The material needs context and framing throughout the chapters. People assume that an author does this very simple thing: asks people questions; writes the answers down. That part is actually the simplest and the most fun but far, far away from an effective, finished product.

I’ve used a number of formats, and I think Actors Talk About Shakespeare and Modern Hamlets and their Soliloquies guide the reader carefully through the interviewee’s methodologies and choices, but those books took years to write. There is a phrase you will hear once an actor has outlined how s/he actually works, how s/he completes the job: “That’s my aesthetic.” This pronouncement already tells you that there are several ways to shape a performance, and that each individual actor has figured out what works for him/her. As an interviewer, you accept that and you honor all those methods. In the actors we chose, the performance is proof of the actor’s process.

EB: Can we hope for more interviews in the future, perhaps a sequel?

MM: One hopes so. It really is too soon to tell.

AA: Certainly there are many more OSF actors whose voices and stories should be heard. But at the moment I’m satisfied to have had a part in capturing twelve of them. I’ve got other projects in the fire now—an essay related to the book, about using contemporary actors as evidence; an essay on doubling of roles in The Comedy of Errors; and another on Prospero’s hat. But first I’m going to spend some time in my kayak.

EB: What surprised you most in the course of the interviews?

EB: What surprised you most in the course of the interviews?

MM: I was surprised and delighted at how many actors responded positively. Not just in terms of all of the individual personalities that a company brings to the table, but the eagerness with which each spoke, and how freely they wanted to share their work creating characters–the whole idea of process within the actor’s art form. These are consummate artists and wonderful story tellers. Even their most outrageous moments onstage were often divine inspiration. We sought to capture both the artist and the artist’s voice, which was truly the crux of the project and demanded discipline, judgment and many conversations about what would work in the book.

Two other story tellers, actor Stacy Keach, an alumnus of OSF, and playwright Robert Schenkkan surprised us both with lovely testimonials for the book’s cover.

AA: Not so much what the actors had to say—because I’ve worked with all but one in the rehearsal room, so I went into the interviews knowing something about them and about their processes, and that’s what we wanted to share with our book’s readers. What did surprise me was their saying that they rarely got the chance to really talk, reflectively and candidly, about how they do what they do. They talk to groups of playgoers or students about their roles, or about the plays they’re in. But the invitation to speak directly about the mysteries of their craft, to try to explain what happens when they’re up there on stage, and all the preparation that goes into making it happen—that’s an opportunity they really welcomed. And that confirms my original conviction that each of these actors is a kind of neglected treasure. As a Shakespeare scholar I’m conscious of the gaps and omissions in our knowledge of how Shakespeare’s plays were acted originally. I hope these interviews will make it easier for someone a hundred years from now to understand the theatre that existed in this moment in this place.

EB: What was the writing and planning process like?

MM: Frankly, we just dove in. I know 10 minutes into an interview whether or not the information is rich, like running your fingers through gold coins. All of these were.

In retrospect, we could have been a bit more cautious about stylistics from the get-go. But Alan turned out to be the Mastermind of Proofreading and shepherded that whole phase through the mire. You never forget that you learn how to write a book by writing the book.

We were forging a new process in removing the authors from the story on the page. That meant we were learning as we journeyed through our own process. Some actors were surprised to see that they were the single public voices in the book. But our outside readers adapted very quickly and with positive responses, so we were relieved that it was working. That did not, however, eliminate our own learning curve—but it certainly sharpened it.

AA: Long, sporadic at first, and always invigorating. We figured out the details, solved the problems, as we went forward. The last six months have been the hardest, pushing toward publication. Earlier, the interviewing was certainly time-consuming, 3-4 hours with each actor (never failing to appreciate that 3-4 hours of their time was a greater gift to us). Transcribing those interviews was incredible donkey work. Imagine how long it would take just to get down correctly the 30,000 words of one interview—and each of us had six to do. My wife, whose sociological research involves a lot of interviewing, kept asking me why I didn’t just pay someone to do the transcriptions. But the kind of intense listening I had to do just to get the words down is what really got the interviews—and especially the actors’ voices—into my head. And that’s what I needed for the next phase, which was arduous in a different way: distilling those 30,000 words into the 7500 or so that would represent, e.g., Danforth Comins. Our focus on actor process guided our choices in this phase, but it was still hard to cut the interviews. I can assure you that Danforth didn’t speak 22,400 boring or irrelevant words to me, words that I could just throw out without thinking. At each stage of editing, pruning was hard, because we had to sacrifice good stuff—e.g., Danforth’s account of his film work—in the interest of even better stuff, like how he prepared to play Hamlet for the second time. When we thought we had done this job as well as we could—at around nine or ten thousand words per interview—it turned out that we were really just beginning the hard work of editing. It took several more rounds of agonizing edits to make the chapters that you’ll find in the printed book. It was a challenge to keep seeing the interviews with a fresh eye, to imagine yourself a reader coming to each chapter for the first time.

EB: Do you edit each other’s work? Fight over commas?

AA: We did read each other’s interviews and make suggestions, but I don’t think either of us is dogmatic enough to have started a comma war. We’re both professionally trained to recognize that grammar and punctuation and syntax and style are often about conventions and preferences, not absolute rules. So we expected that our “rules” and preferences would differ, and that Mary’s interviews would have a different style of punctuation from mine (how much we used dashes or semicolons, or how we chose to emphasize words—italics? boldface type? capitals?). We were able to negotiate conspicuous differences, thinking mostly about how our choices would affect readers. No accent mark in Moliere, for instance, or footnotes, or citations—it’s an informal book. What made editing easier was a special circumstance of this book: we weren’t trying to impose our individual styles and voices. What we both were trying to do was to capture the actors’ individual voices—their rhythms, their vocabularies, their conversational styles. That goal trumped grammar and punctuation. We didn’t want to be “correct”; we wanted you to hear those voices in your head as you read the interviews, as we heard them when the tape recorder was rolling. I realized just now that I was starting to channel Jonathan Haugen there, except that he would have said: “We didn’t want to be correct. #%$!@&* correctness! Who cares? We just wanted you to hear those voices.”

AA: We did read each other’s interviews and make suggestions, but I don’t think either of us is dogmatic enough to have started a comma war. We’re both professionally trained to recognize that grammar and punctuation and syntax and style are often about conventions and preferences, not absolute rules. So we expected that our “rules” and preferences would differ, and that Mary’s interviews would have a different style of punctuation from mine (how much we used dashes or semicolons, or how we chose to emphasize words—italics? boldface type? capitals?). We were able to negotiate conspicuous differences, thinking mostly about how our choices would affect readers. No accent mark in Moliere, for instance, or footnotes, or citations—it’s an informal book. What made editing easier was a special circumstance of this book: we weren’t trying to impose our individual styles and voices. What we both were trying to do was to capture the actors’ individual voices—their rhythms, their vocabularies, their conversational styles. That goal trumped grammar and punctuation. We didn’t want to be “correct”; we wanted you to hear those voices in your head as you read the interviews, as we heard them when the tape recorder was rolling. I realized just now that I was starting to channel Jonathan Haugen there, except that he would have said: “We didn’t want to be correct. #%$!@&* correctness! Who cares? We just wanted you to hear those voices.”

MM: We fought over virgules (Alan won) and we fought together for colons, which neither of us won.

And yes, we edit one another’s work. You really have to, or you lose perspective if you only write in your own little cubbyhole all year long. I value Alan’s suggestions very much, and I suspect I am a different kind of editor to him than he is to me. I am sure that we both benefit greatly from one another’s point of view. The editing process is hugely long and complicated, and we pride ourselves on having a sense of decorum and even a sense of wonder about the quality of the material we got in interview.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

AA: Thanks, Ed—always a pleasure to talk with you.

MM: Thanks.

Follow

Follow