Peter Laufer is a journalist, broadcaster and documentary filmmaker and he holds the James Wallace Chair in Journalism at the University of Oregon. He is the author of 20 books on such topics as the media, immigration, natural history, and crime. He has a Master’s Degree from the American University in Washington, DC, and a Ph.D. in Cultural Studies from Leeds Metropolitan in England.

Peter Laufer is a journalist, broadcaster and documentary filmmaker and he holds the James Wallace Chair in Journalism at the University of Oregon. He is the author of 20 books on such topics as the media, immigration, natural history, and crime. He has a Master’s Degree from the American University in Washington, DC, and a Ph.D. in Cultural Studies from Leeds Metropolitan in England.

Laufer was a correspondent for NBC News and the charter anchor of the radio program “National Geographic World Talk,” a nationally-syndicated show he created.

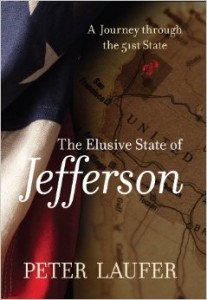

We sat down to talk about his most recent book: The Elusive State of Jefferson: A Journey through the 51st State, available from Globe Pequot Press.

EB: What got you interested in the State of Jefferson?

PL: Borders, identity and migration fascinate me. After I finished a book that focused on California’s southern border, it occurred to me that I should look at the less spotlighted northern border. Once I started the preliminary research I realized that the so-called State of Jefferson movement not only is intrinsically intriguing, it serves as a metaphor for the ghastly schisms we Americans are suffering nationwide. The Elusive State of Jefferson offers a grand adventure combined with a cautionary tale.

EB: You’ve told the story as a narrative of your research. Any particular reason you chose that style?

PL: I fancy myself a storyteller. I want the reader to come along with me as I travel the Jefferson backroads. I want the reader to meet the strange-but-true characters I meet during my journey. And I want the reader to consider the broader lessons of Jefferson for all of us. For these goals a narrative approach seems most alluring.

EB: Mayor Gilbert Gable died on Dec. 5, 1941—right after the initial vote to secede and right before the attack at Pearl Harbor. Would things have turned out differently if he’d lived?

PL: Not for the Jefferson movement. Even without the Pearl Harbor attack, the publicity stunt that was 1941’s Jefferson (just as today’s resurgence is a publicity stunt) had already run its course. I wager PR expert Gable would have been the first to recognize that the gambit served its purpose. The next act for him and Jefferson would have been to parlay the notoriety into productive engagement with Salem and Sacramento.

EB: How much of the 1941 secession—the roadblocks, the Proclamation of Independence, etc.–were just publicity stunts?

PL: 100 percent.

EB: What was the appeal of the story nationally? The San Francisco Chronicle coverage won a Pulitzer! And you mention that the secession vote made the front page of the New York Times in 1941.

EB: What was the appeal of the story nationally? The San Francisco Chronicle coverage won a Pulitzer! And you mention that the secession vote made the front page of the New York Times in 1941.

PL: The appeal of the story nationally was diversion and entertainment – both admirable goals. As is the case today, the nation was weary of war talk. We Americans love underdogs and seemingly independent Wild West characters. The Jefferson fairytale, then and now, suggested a quick fix for frustrations. Trouble for those who took it too seriously – then and now – is that both politically and financially there is no realistic case for Jefferson, as I explain in detail in the book. There never will be a State of Jefferson.

EB: Was there a specific issue that got people so riled up in 1941?

PL: Bad roads and irritation with feeling ignored by the rest of Oregon and California.

EB: Much of the book describes present day secessionists. In early September, in fact, the Siskiyou County Board of Supervisors voted 4-1 to secede. Are the issues different now that they were in 1941?

PL: Modoc County followed a few weeks later. They both need to look at their budgets. More tax dollars come up from Sacramento to provide these rural counties with needed social services than they send south. What are the issues? The rebels today feel their individual rights are being trampled by urbanites. They should read their Constitutions.

EB: What do you see as the future of these counties in southern Oregon and northern California?

PL: Tourism. Information industries. Timber and mining are yesterday’s news. As I suggest in the book, if the Jefferson proponents really think they can go it alone they should change the name of their nascent state to Garbo. The actress was famous for wanting to be left alone. Jefferson, on the other hand, saw the advantages of working together. (That is if they mean Thomas. If they mean Jefferson Davis, that’s another story.)

EB: You delve into the culture of the State of Jefferson. What sort of a cultural identity has evolved? Are there differences between the California parts of Jefferson and the Oregon parts?

PL: An unfortunately fractured cultural identity has evolved with competing interests at odds over water, land use, timber, fishing, tribal rights and the rule of law. Perhaps that’s why the escapism of the statehood movement charade is so appealing.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

Follow

Follow