Buried Prey

John Sandford is another of those stay up later-than-you-should authors and I’m still hooked on his Lucas Davenport series (and now on the spin-off Virgil Flowers books as well). What I like is that Stanford puts us as much energy into the endings of the stories as he puts into the beginnings. The books also have a recurring ensemble of interesting characters, who are Minnesota-nice but still break the rules when they need to. And Davenport has a quality of sprezzatura–making things look easy–even when he stymied.

Buried Prey is a flashback novel. Missing bodies from Davenport’s first case are discovered and he reopens the investigation in his usual stir-up-the-pot fashion. The part of the book set in the past takes us back to Davenport’s short-lived patrol days in his first meeting with some of the other characters in the ensemble. And (spoiler alert) one of the recurring characters is killed.

Bright-sided: How Positive Thinking Is Undermining America

I’ve been fascinated with the American fascination for success ever since I read Dale Carnegie’s How To Win Friends And Influence People in high school. And lately I’ve read some of the scholarship of success, like a Richard Huber’s The American Idea of Success, Micki McGee’s Self-Help, Inc: Makeover Culture in American Life, and John Ramage’s Twentieth-Century American Success Rhetoric: How to Construct a Suitable Self. In Bright-sided, Barbara Ehrenreich puts her own mark on the topic with a lively history of new thought, positive thinking, business training and happiness studies. Along the way, Ehrenreich exposes the pseudoscience of positive thinking analogies–from magnetism to quantum physics, which in the kookier versions are said to made up the science of positive thinking. She takes us through business leadership, which is today less about the leader as manager and more about the leader as charismatic figure (think Donald Trump and Kenneth Lay). And she explains use of positive thinking is used in the workplace as social control—nobody likes Negative Nancy!

Along the way there is some recycling of familiar Ehrenreich themes, but she gives us plenty to think about, such as the “motivation junkie” who came from a background where she hadn’t encouraged to succeed and through motivation workshops saw herself as a potential success. Toward the end, Ehrenreich she gets to the central problem of positive thinking—how do you avoid unproductive negativity but still avoid unrealistic optimism. That’s the balance that we all need to find.

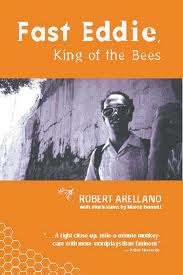

Fast Eddie–King of the Bees

Everyone likes a good dystopia, from Wells and London to Zamyatin, Huxley, Orwell, Burgess and M. T. Anderson’s Feed. In Fast Eddie–King of the Bees, Robert Arellano takes us to the dystopic Boston of the near future, where a big-footed pickpocketing contortionist becomes the leader of underground Dig City.

Everyone likes a good dystopia, from Wells and London to Zamyatin, Huxley, Orwell, Burgess and M. T. Anderson’s Feed. In Fast Eddie–King of the Bees, Robert Arellano takes us to the dystopic Boston of the near future, where a big-footed pickpocketing contortionist becomes the leader of underground Dig City.

Eddie, the pickpocket, starts out as a street orphan mentored by Shep, the faux blind street professor who schools his rats in both grifting and the liberal arts. Eddie leaves Shep’s tuteledge in search of his birth parents, but Pauly (the Mayor of Ho-Ho-Kus, New Jersey) and his wife Merry (as in Christmas) fall short. Eddie finds himself falling back through the rabbit hole to the underground city. There’s an Oedipal subplot or two—read the title slowly and a little backward and you can get to Oedipus, King of Thebes. There’s plenty of other nameplay and wordplay too (go reread Oedipus and match up the names their Greek counterparts for fun). And for the English majors out there, the book caused me to wonder what extent dystopian stories reinforce the traditional heroic values and reproduce classic themes.

The Eye: A Natural History

Last year I had cataract surgery and (in an unrelated genetic mishap) a tear in my retina. So the eye is on my mind.

Simon Ings’s book takes us there. Ings covers how the eyes has evolved, the history of eye physiological research, theories of vision, the senses in general, and the relation of seeing to thinking (and vice versa). Better yet, Ings is a good writer and he captures the reader’s interest from the get go, with depictions of cyclopses, vivescetion, daughter as an embryo, Helen Keller, and his daughter as an embryo. How can you not be interested?

And there is something for writers to learn here as well. Early on Ings describes the challenge of organizing his material as a writer. He needs to deal not only with the human aspects of vision but the science and psychology.

How to organize such diverse material? Two solutions presented themselves – as obvious as they were useless. I could describe how eyes came to be, tracing their evolution and development from their biochemical origins to their modern forms. And how dull that would have been: to plunge my reader-victims first into the toils of organic chemistry, then into the niceties of evolutionary interpretation, without a word said about why the story of the eye was all worthwhile or interesting. This would hardly be a story at all, because it would have to fan out, as the eye is fanned out over evolutionary time, into myriad forms, countless small tales of variation in innovation. It would have resembled a failed experiment in hypertext fiction – lots of promising great openings, but no satisfaction, no ending, no shape.

The obvious (and equally wrong) alternative was to write a ruthlessly simplify history of how certain men and women came to understand the eye. The trouble is, the eye is not one story. It is many. To preserve the chronology, every paragraph of the book would’ve had to begin with “Meanwhile…” or “Coincidentally…”

My solution is, I concede, little strange. It is a reflection of my own journey to the literature of the eye – a tale of wonder, and confusion, and flashes of understanding.

Good advice. One small catch for me was the English language, as opposed to the American one. Ings is British and while I’m usually happy to read books in English English, sometimes the small differences—short-sighted as opposed to near-sighted, and optician rather than optometrist—yanked me out of the exposition inopportunely. Still, this is a book to be savored, or savoured if you prefer.

Two-bit Culture: The Paper Backing of America

Before everyone was worried about the e-book, they worried about paperbacks, so I’m rereading Two-Bit Culture, Kenneth Davis’s 1984 study of the history of mass-market paperbacks. This was written before Davis began his Don’t Know Much About books, but he brings the same kind of attention to small details and large trends to this work. He begins, after a nice opening case study of Dr. Spock’s baby book, taking us back to the founding of Pocketbooks by Robert de Graff books, Tachnitz editions in Germany, and Allen Lane’s Penguin books. He takes us through the depression, the emergence of the blockbuster book, and the female romance genre of Harlequins and Avon all away up to the era of consolidation under Bertelsmann and others (little did he know…).

There are plenty of illustrations of paperback covers (including the James Avati cover of Catcher in the Rye which so angered J. D. Salinger that he changed publishers).* And Davis gives a nice treatment of one of my favorite topics, the 1950s Congressional investigations linking paperback books and moral decline.

Two Bit Culture is less fun to read than Janice Radway’s A Feeking for Books (about the Book-of-the- Month Club), but it has way more meat than Michael Korda’s Making the List, which just lists bestsellers with a little introductory essay. What is especially nice about Davis’s book for me (besides nostalgia) is the insight it gives into the relationship between distribution networks and publishing trends. The earliest paperbacks were mostly for men, since they were the most likely to visit the places where paperbacks were sold – newsstands and so on. As distribution expanded and buying power and patterns changed, new literary markets opened. That’s happening again with ebooks. Someone needs to write Two-byte Culture: The Ebooking of America or something.

(*Salinger had insisted that Holden Caulfield not be pictured.)

Follow

Follow