Educator and musician Irv Lubliner of Ashland retired from Southern Oregon University in 2014 after teaching mathematics for forty years, working with every grade from kindergarten through graduate school. He recently edited and published his mother’s writing and oral presentation transcripts about her experiences living through the ghettos and concentration camps during the Holocaust.

Educator and musician Irv Lubliner of Ashland retired from Southern Oregon University in 2014 after teaching mathematics for forty years, working with every grade from kindergarten through graduate school. He recently edited and published his mother’s writing and oral presentation transcripts about her experiences living through the ghettos and concentration camps during the Holocaust.

Born in 1922 in Poland, Felicia Bornstein Lubliner was deported from the Lodz Ghetto to the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1944, and later to the Gross-Rosen concentration camp. After liberation from the camps, she married Abram Lubliner, who she met at a camp for displaced persons, and the couple made their way to Oakland, California. She died in 1974.

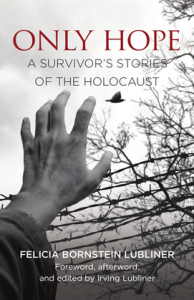

The book, for which Irv wrote the foreword and afterword, is Only Hope: A Survivor’s Stories of the Holocaust, published by Felabra Press.

Ed Battistella: Tell us about your mother.

Felicia Bornstein Lubliner

Irv Lubliner: My mother was one of eight children and grew up in a household that also included her grandmother. She was the only member of that large family to survive the Holocaust. While we might refer to her as “the lucky one,” she felt tremendous guilt about being the only survivor, always wondering what she might have differently to help the others stay alive.

Once in the United States, she began to study English (probably at Laney College in Oakland, though I was too young to have paid attention). I don’t know what compelled her to start writing about her Holocaust experiences, but it may be that she felt a moral obligation to see to it that the horrors she survived were not “swept under the rug,” that the world would come to grips with what had taken place, and that no such thing would ever happen again.

Though my parents, in keeping with Jewish tradition, lit memorial candles for their lost loved ones, the names of those deceased relatives were never spoken in my home, and there was no talk of what they had experienced. My mom and dad seemed determined to give me a “normal” American upbringing, without my fearing that my life, my education, and my sense of security would be disrupted as theirs had been. She wrote the stories that I compiled in the book and spoke each year to a class studying the Holocaust at San Francisco State University, but she and I never had an adult conversation about her life prior to coming to the U.S. At the time of her death, she was only 51, and I was 21.

EB: Given that your mother passed away in the 1970s, I’m wondering why you chose this moment to put her remembrances and speeches together as a book.

IL: For about thirty years, I’ve been visiting school classrooms (from middle school on up) to share my mother’s writing, reading the stories aloud and engaging students in conversation about them. I would often have parents contact me afterwards, telling me that their children had spoken of the stories at home and asking if they, the parents, could read them. I received tremendous encouragement—from students, teachers, and parents—to get the stories published, and have lived with that goal in mind for a very long time. I wanted to contribute something to the work, reflecting on my own experience as the child of two Holocaust survivors. It wasn’t until 2014 and my retirement from SOU that I, with the help of two writing coaches, finally wrote something that lived up to my own standards and that said what I felt needed to be said. Within the last year, I created my own publishing company, Felabra Press (honoring my parents by using a juxtaposition of their names, Felicia and Abram), and the book became available in May of this year.

A few days ago, I received an unsolicited testimonial comment from an Emeritus Professor of European History, Edward Gosselin, which read: “This is the most moving book I have ever read about the Holocaust and about Auschwitz.” This reflects my mother’s effectiveness as a writer and demonstrates that her stories have something to offer to all, those who have studied the Holocaust extensively and those who know little or nothing about it.

EB: All of the narratives were very heart-rending but I was especially horrified at the “Concert at Auschwitz,” which was published in the San Francisco Chronicle. Had you read any of your mother’s writings as you were growing up?

IL: No, I have no recollection of reading that story (which appeared in a Sunday supplement to the SF Chronicle in 1961) or any of the others while I was growing up. By the time I was old enough to read and appreciate them, I was a rebellious teenager, constantly trying to keep my distance from my parents and do “my own thing,” and I passed on the opportunity. When we got word of my mother’s terminal cancer in 1974, I was a senior at U.C. Berkeley, no longer living at home. That would have been a good time for a conversation with my mother about her experiences, but I knew that would be a painful conversation, and it was not one that I chose to initiate.

Getting back to “Concert at Auschwitz,” I think it’s worth noting that its publication came within twelve years of my mother’s arrival in this country and is written in English, which was, for her, a new language. All of the stories in Only Hope are written in English and readers often comment about how skillfully she wrote.

EB: Your father also survived imprisonment in a concentration camp during the Holocaust. But he responded much differently—you said he only spit when the topic came up. What did you make of his reactions?

IL: In the foreword, I mention a specific incident in which my father spit on a German postage stamp from the time of the Nazi regime, one that bore Hitler’s picture and a swastika. It made an indelible impression on me because it was so rare to see my father show any emotional response or share information about what he had endured, what he had lost, or how his experiences had scarred him. I only saw my father spit on that one occasion, but it was powerful. It saddens me that he never found a way to release the grief and bitterness that he must have felt.

EB: What was it like to edit your mother’s stories?

IL: Though my mother wrote in English, not in her native language, Polish, her stories did not require any editing. My role as editor was really limited to deciding in what order the stories should appear in the book and choosing which of two drafts of a given story would be used. While I was a child, she took classes to learn English, mastering not only the language, but also the craft of writing a short story. One more thing I’ll mention: She was a force to be reckoned with if you played Scrabble with her. Her vocabulary was much more extensive than the typical person raised in this country and speaking English since childhood.

EB: How can people get a copy of Only Hope?

IL: I have chosen not to turn the book over to the big-name booksellers such as Amazon or Barnes & Noble. Instead, it is being sold through my website, onlyhopebook.com, various Holocaust museums and education centers, and at a number of independent bookstores (including Bloomsbury Books in Ashland, Rebel Heart Books in Jacksonville, and Oregon Books in Grants Pass).

I hope that the book will find its way into school classrooms, and I am offering a 25% discount to educators ordering twelve or more copies.

EB: Besides the website mentioned above, is there any other place people can get more information about the book?

IL: I was recently interviewed on our local NPR radio station on the Jefferson Exchange program. Anyone interested in hearing the interview can do so by visiting this site:

https://www.ijpr.org/post/local-author-publishes-mothers-memories-holocaust#stream/0

EB: Oregon recently passed legislation requiring school districts to provide instruction specifically about the Holocaust. What other books or resources on the Holocaust would you recommended?

IL: I am very pleased that Holocaust- and genocide-related instruction is now a mandated part of the curriculum here in Oregon. What people might not realize is that the push for that legislation came from a high school student in Lake Oswego, Claire Sarnowski, who was inspired to contact her district’s state Senator after a Holocaust survivor visited her school back when she was in 4th grade. This illustrates how impacting stories such as those my mother wrote can be on younger learners. By the way, I sent Claire an inscribed copy of Only Hope, thanking her for her efforts to see to it that the stories of the Holocaust would be passed on to her generation and those that will follow.

In recent years I have been immersing myself in Holocaust-related books, articles, and films, so I could easily compile a long list, and it is difficult to narrow it down. Here is an attempt to do so, focusing on titles that your readers may have missed:

-

• Maus 1: A Survivor’s Tale: My Father Bleeds History and Maus 2: A Survivor’s Tale: And Here My Troubles Began by Art Spiegelman

• The Cap: The Price of a Life,,, by Roman Frister

• Human Smoke: The Beginnings of World War II, The End of Civilization, by Nicholson Baker

• Suite Francaise, by Irene Nemirovsky

• The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, by John Boyne (both the book and the film)

• Sarah’s Key, by by Tatiana de Rosnay (both the book and the film)

• Shoah, by Claude Lanzmann (both the book and the film)

I’m sure I’ll soon remember something else that deserved to be on that list!

EB: Thanks for talking with us and thanks for what you are doing.

IL: I appreciate this opportunity to share information about Only Hope: A Survivor’s Stories of the Holocaust. Thank you very much, Ed.

Follow

Follow