Photo: © Jeff Bark

Sam Anderson is a staff writer for The New York Times Magazine.

An award-winning journalist, he has been a book critic for New York Magazine and a regular contributor to Slate. He lives in New York.

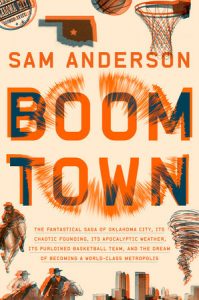

Boom Town, published in 2018 by Penguin Random House, is his debut novel.

Ed Battistella: I really enjoyed Boom Town. You’re an Oregonian, originally, so what prompted you to write a book about Oklahoma City?

Sam Anderson: Thanks! You’re right — people often assume only an Oklahoman would write a book about Oklahoma, but I had zero connection to the place. I grew up in Oregon (born in Eugene, college in Ashland) and also Northern California; since then I’ve lived in Louisiana and New York. My interest in Oklahoma didn’t start until 2012, when the New York Times Magazine, where I’m a staff writer, sent me to OKC to write an article about its new basketball team, the Thunder. The team had just made the NBA Finals on the strength of its three very young superstars: Kevin Durant, Russell Westbrook, and James Harden. So I went out to write about the relationship between this small city and its big-time sports team.

I’ve been waiting my whole magazine career for a subject to force me to write a book about it — and to my surprise, Oklahoma City turned out to be it. The place swept me away. There was this mixture of epic history and huge personalities and a unique landscape. I spent as much time as I could there, and everywhere I looked the connections and themes and material deepened. It became a magical project that consumed my whole life.

EB: After reading the book, Oklahoma City seems like an old friend to me, though I’ve never been there. Was part of your goal to make the city a character itself?

SA: I’m glad to hear it. Yes, the goal was to tell the whole story of this city, from the moment of its founding to today. Historically speaking, it’s a ridiculously young city — it was founded in 1889 — so I felt like I could get my arms around that whole history. By the end of it, the reader should know the place inside and out — not just the big flashy news events (the 1995 bombing, the rise of the OKC Thunder) but the low times and the boring times. This gives context to what those big flashy news events actually *mean* to the city.

EB: You’ve worked most of your career as an essayist and cultural critic. What was the experience like of doing a non-fiction book?

SA: It was exhilarating but also very, very hard. As I said before, I’ve been waiting for many years for a book project to come along and sweep me away. All of my writing heroes (John McPhee, Annie Dillard, Janet Malcolm, Joan Didion, et al.) have written great nonfiction books. So I knew I’d tackle one eventually. But it was a slog. I took an 8-month leave from my job at the Times Magazine to try and bang it out — those were very long, strange days: I’d wake up at 5 in the morning and go to my office and write for 8 or 10 or 12 hours. After all those months, I had some of the core parts of the book written — but there were still many years to go. My original deadline was one year. In the end, it took me more than five. There was a lot of agony. But I was lucky to work with a great, great editor at Crown, Kevin Doughten, and the project became a deep collaboration with him. And I’m really proud of the finished product.

EB: Basketball and the Oklahoma City Thunder play a part in the recent history of the city—you call it a purloined team. Reading the book, I had the feeling that your book was organized a bit like a basketball game—that you were passing the ball along among interesting topics and characters—Kevin Durant and Russell Westbrook, Gary England, Wayne Coyne, and others. Was that in your mind as a structural device?

SA: That’s fascinating. No! I didn’t think about passing a basketball around as a structural device. But that is pretty accurate. The structure was really hard to work out and developed through trial and error over years of writing. I tried to impose various structures (for a short crazy time I thought about organizing it based on the underground architecture of a prairie dog colony) but in the end decided that the book should find its own shape, exactly like OKC did in 1889 — which is to say, it should be a ridiculous pile of chaos that eventually, against the odds, found equilibrium. Which I think is an accurate description of the book.

EB: One of the themes of the book seemed to me to be the idea of process—in characters like Sam Presti and Angelo Scott. You seem to be portraying Oklahoma City as the tension between orderly process and booming exuberance.

SA: Yep, you got it. From the moment of its conception, the place has been on the brink of spiraling out of control. And there have been these key figures who have stepped in, at crucial moments, as master organizers and held everything together. Presti with basketball, Angelo Scott as a settler who kept the place from exploding into civil war, Clara Luper as a Civil Rights hero who integrated downtown. My goal was always to find those master organizers and show them battling the chaos of their moment. Then of course the city would produce some other kind of chaos that had to be overcome, and someone else would have to step in to deal with it.

EB: Can you tell us about the title? The book seems to resonate with booms, literal and metaphoric.

EB: Can you tell us about the title? The book seems to resonate with booms, literal and metaphoric.

SA: Yes — the place started as a literal “boom town,” a patch of prairie suddenly overrun with people looking to make a fortune. Since then it has bounced up and down on the boom and bust economy of the energy industry. It gets rich overnight, then poor overnight. So the notion of a “boom” runs through the history of the place, literally and metaphorically, in important ways and trivial ways. Russell Westbrook, the basketball star, used to scream “BOOM!” every time he made a three-pointer. And that’s all before we get to the defining trauma of OKC: the 1995 bombing of the federal building in the middle of downtown, an explosion that killed 168 people and scarred just about everyone in the city for generations.

EB: What surprised you the most in doing the research?

SA: There is a section of the book called “Operation Bongo” that contains the most surprising research discovery I’ve ever made, or (I’m convinced) ever will make. I won’t spoil it here, but it’s a bizarre connection between Seattle and Oklahoma City from the 1960s — it seems to foreshadow OKC taking Seattle’s basketball team 40 years later. It’s like a Borges story. My jaw dropped. I couldn’t have invented it if I tried.

EB: Any plans to take on another city?

SA: Nope. I’m happy having done this one city. Now I’m back to writing magazine articles, waiting for the spirit to move me for my next book project. If it’s another city, I guess I’ll have to write about another city.

EB: Thanks for talking with us. I really loved the book.

SA: Thanks so much!

Follow

Follow