Ed Battistella: How did Rose Alley Press get started? The name Rose Alley has a special connection to John Dryden. Can you tell us a bit about that?

David D. Horowitz: I founded Rose Alley Press on November 17, 1995. Dissident Nigerian playwright Ken Saro-Wiwa had just been executed, and Israeli politician Yitzhak Rabin had just been assassinated. I was also upset after four years of less-than-favorable involvement with some religious groups. By 1995, I had articulated and wanted to publicize a form of freethinking deism based on the twin ideals of consideration and vitality—as opposed to faith in a messiah, absolute allegiance to a holy book, surreptitious curtailment of basic individual rights by tribalistic authority, and presumed divine sanction for appropriating land and political power. I had founded and managed two small presses before: Urban Hiker Press, 1979 through 1981; and Lyceum Press, 1988 through 1990. Those two enterprises never amounted to more than self-publishing operations. This time, I wanted to publish not only my own work but that of other writers. I had a long-standing commitment to rhymed metrical poetry, so I wanted that to be a twin pillar of my new publishing company.

I had felt harassed and hounded in the late eighties and early nineties. This is a long story, the details of which I’d rather not discuss at this time. I sympathetically identified with John Dryden because of the December 18th, 1679, attack in Rose Alley, London, that nearly cost him his life but didn’t stifle his poetic voice. As my landlord’s surname was Rose, and I lived in an alley, I thought the name “Rose Alley Press” appropriate. I also loved the way “Rose” and “Alley” suggested poetry could be about both the esoteric and mundane, the beautiful and the plain. Therefore, I called my new company “Rose Alley Press.”

The first two books I published were my own eclectic collection of essays and epigrams, Strength and Sympathy, and a fine chapbook of poems, Rain Psalm, by my friend and fellow poet, Victoria Ford. This was the spring of 1996. The books sold credibly, and I enjoyed promoting them, so I decided to publish a third book. I asked my primary literary mentor, William Dunlop, a University of Washington English professor, if he would consider submitting his poems to me for possible publication. He had turned me down in 1990, but this time he agreed. A native of Britain, William wrote primarily in rhymed metrics and with Philip Larkin-esque descriptive precision. I loved William’s under-appreciated work! Nine months later, on June 17th, 1997, and after much scrupulous editing, William Dunlop’s collection, Caruso for the Children, & Other Poems, was published. Measured by poetry book standards, it was a “hit.” In my free time, away from my day job, I was running around town fulfilling bookstore orders, planning and promoting readings featuring William. To date, the book has sold 750 copies, which is quite good for poetry. It was the first book I’d published that genuinely sold well–400 copies in its first six months–and which was fairly widely reviewed and publicized. I was hooked!

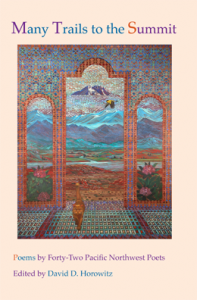

A succession of poetry collections followed: Michael Spence’s Adam Chooses; my own Streetlamp, Treetop, Star; Douglas Schuder’s To Enter the Stillness; Joannie Stangeland’s Weathered Steps; Donald Kentop’s On Paper Wings; and several more of my own collections. My own work was written almost exclusively in rhymed metrics, and at least half of the poems in the other collections were in rhymed metrics. Sales were solid, well into the hundreds for each title. Readings were increasingly well-attended and often at fine venues like Elliott Bay Book Company, University Bookstore, Powell’s on Hawthorne, the Frye Art Museum, and Bumbershoot Arts Festival, among other venues. Still more poetry collections followed, focused on rhymed metrics. These included two Pacific Northwest anthologies I’d edited: Limbs of the Pine, Peaks of the Range (2007) and Many Trails to the Summit (2010). Rose Alley Press was becoming a respected, fairly reputable name in the Seattle-area literary scene–and so it remains to this day. I claim no fantastic fame or financial success–but an earned respect, yes, and I’m glad for that.

EB: Tell us a little about your background. How did you become a publisher?

DH: I was born in New York City in 1955. My father was a sociology professor who frequently moved from job to job. Indeed, when I was two, we moved from New York City to Waltham, Massachusetts; and then to Barrytown, New York; Annandale, New York; Geneva, New York; and University City, Missouri–just outside of St. Louis. That was only by the time I was seven. I lived in University City from 1963 to 1971. My parents divorced in 1964, and my father eventually returned to New Jersey to teach at Rutgers. I got along far better with my mother than with my father, so when she earned her Ph.D. in political science from Washington University in St. Louis and got a job teaching political philosophy for the political science department at the University of Washington, I moved with her to Seattle.

My mother helped create a home environment devoted to free, honest inquiry, which was perfect for me. In 1973 I graduated from Seattle’s Lincoln High School and attended the University of Washington, majoring in philosophy. Early during my UW years, I began keeping a poetry journal. I’d scribble all manner of banality during and after long walks and bike rides to Ballard, Magnolia, Carkeek Park, or downtown. But one warm summer evening in 1974 I felt entranced and haunted by the beauty of the sunset. I couldn’t quite describe the color, but I felt impelled to try. For three consecutive weeks that August I gazed at the Olympic Mountains at twilight, backed by a fabulous mix of peachy reddish colors. I struggled to describe the colors, but finally one evening it struck me: salmon! That was the color! Not red-orange-purple-pink, but salmon! And the word was so rich in Northwest connotation, too! Well, that was it. I derived such intense pleasure from finding that right word, that essential bit of description, that I cultivated my poetry journal habit.

My emerging love of poetry prompted me to seriously pursue writing as my primary avocation. My last quarter as a philosophy major undergraduate at the UW, I decided to take an introductory poetry composition class. My teacher was British: William Dunlop. He was brilliant. And he loved rhyme as much as I did. He introduced me to the work of several influential contemporary poets, including Richard Hugo, Denise Levertov, Elizabeth Bishop, and probably his favorite (then) contemporary poet: Philip Larkin. I loved that Larkin wrote rhymed metrical poetry. I read Larkin’s The Whitsun Weddings virtually every day in 1978, my first year out of school. I would also occasionally visit Dunlop in his office. We chatted. I got to know him a bit better. I read some of the verse he’d published in various journals over the years: journals such as TLS, Poetry Northwest, Encounter, The New Statesman, and some much lesser known. Some of his poems were brilliant. And yet he was a virtual unknown seemingly without a published collection who confided to me that he did not write much verse anymore. He once said to me in his dusk-darkened office, after a long pause: “There are worse things to be than an honest failure.” This moved me. I felt some instinctive anger that the literary world often rewarded writers for reasons of fame and fashionable political commitments, not genuine artistry.

My sense that Dunlop had been slighted is the seed that yielded Rose Alley Press. I founded a small press in 1979 called Urban Hiker Press and through it published my own chapbook, Something New and Daily. I worked at Seattle Public Library but re-enrolled at the UW to complete the course work necessary to obtain a B.A. in English. I earned my B.A. in English in 1981 and in 1983 went to graduate school at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. There I studied under Donald Davie, who I came to learn had been Dunlop’s teacher at Cambridge and was largely responsible for his getting a job at the UW. Academic life and I had our disagreements, so, despite having grown greatly during my four years there, I left Vanderbilt in 1987 and returned to Seattle. I soon founded another small press, Lyceum Press, and published my second collection of verse and a few bookmarks. I was about to begin publishing an anthology of eighteenth-century verse when, for various reasons, my life collapsed. I ended Lyceum Press and never wanted to publish another syllable again.

Through all manner of fateful convolutions I wound up in 1991 teaching and tutoring English at Seattle Central Community College and, to a lesser extent, Shoreline Community College. I began studying math and science at Seattle Central, but my commitment wasn’t deep, and I kept writing poetry. Well, as I indicated earlier I founded Rose Alley Press in November 1995, published William Dunlop’s collection in 1997, and, primarily funded by my job as a conference room attendant at a Seattle law firm, I’ve kept Rose Alley Press going. It’s just about twenty-two years old now, and I’m working on the seventeenth Rose Alley Press book, our third Northwest poetry anthology. I recently retired from my job, so I have some more time now to devote to publishing. There’s so much more to tell, but this is enough. I’ll trust you get some sense of what my motivations and history are.

EB: Rose Alley specializes in poetry and is very selective. What do you look for in a book and in an author? Does Seattle have a particularly thriving poetry community?

DH: I primarily publish books featuring contemporary Pacific Northwest rhymed metrical poetry. Poetry for me is the intersection of language and music, and skillfully employed rhymed metrics deepen resonant engagement with the language. A good formal poem is a community of words, a snowflake in words–but only if its formal elements are realized skillfully, and often with just the right mix of the earthy and esoteric, the conversational and courtly, the humorous and respectful. I like formal verse that shows facility and familiarity with an occasional complex rhyme scheme; diverse forms and tones; enjambment; felicitous melding of subject and form; less-than-obvious but convincing rhymes consistent with a poem’s level of diction; and no gratuitous syllables or cloying rhymes just to fill out a pattern. I also look for the ability to set a scene through distinctively worded images and line breaks hinting at double and triple meanings. I like radical concision: poems without one wasted word. And I like to see familiarity with the great world tradition of poetry. And there we begin to touch on issues of character, beginning with the humble awareness the poet’s own (lack of) fame is not the only issue currently on the planet. I like to deal with a poet well-read in the tradition; with strong aesthetic opinions AND the patience to respectfully consider diverse perspectives. I certainly also prefer poets who can consider editorial suggestions without construing every suggestion as a personal slight. In short, I like someone who can understand and work with me to bring his or her poems to perfection prior to publication. And after publication, I like a poet who will help publicize his or her book through numerous readings, signings, launch parties, and conference teaching gigs. A good set of journal publications is always nice, but more important is the desire and social skill necessary to sell the book directly to people. And, yes, there are many such poets in the Seattle area. I’ve been lucky enough to meet, hear, and publish the work of many of them.

DH: I primarily publish books featuring contemporary Pacific Northwest rhymed metrical poetry. Poetry for me is the intersection of language and music, and skillfully employed rhymed metrics deepen resonant engagement with the language. A good formal poem is a community of words, a snowflake in words–but only if its formal elements are realized skillfully, and often with just the right mix of the earthy and esoteric, the conversational and courtly, the humorous and respectful. I like formal verse that shows facility and familiarity with an occasional complex rhyme scheme; diverse forms and tones; enjambment; felicitous melding of subject and form; less-than-obvious but convincing rhymes consistent with a poem’s level of diction; and no gratuitous syllables or cloying rhymes just to fill out a pattern. I also look for the ability to set a scene through distinctively worded images and line breaks hinting at double and triple meanings. I like radical concision: poems without one wasted word. And I like to see familiarity with the great world tradition of poetry. And there we begin to touch on issues of character, beginning with the humble awareness the poet’s own (lack of) fame is not the only issue currently on the planet. I like to deal with a poet well-read in the tradition; with strong aesthetic opinions AND the patience to respectfully consider diverse perspectives. I certainly also prefer poets who can consider editorial suggestions without construing every suggestion as a personal slight. In short, I like someone who can understand and work with me to bring his or her poems to perfection prior to publication. And after publication, I like a poet who will help publicize his or her book through numerous readings, signings, launch parties, and conference teaching gigs. A good set of journal publications is always nice, but more important is the desire and social skill necessary to sell the book directly to people. And, yes, there are many such poets in the Seattle area. I’ve been lucky enough to meet, hear, and publish the work of many of them.

Indeed, I’d happily claim Seattle DOES have a particularly thriving poetry community. We’ve got fine writing programs and instructors at the UW, Seattle University, Seattle Pacific, and numerous other colleges in the area. Excellent bookstores and reading venues remain plentiful, and the talent level is high. And I think, as well, many of the poets are friends in the best sense: there for each other, thoughtfully honest, and committed to excelling the craft. Are improvements possible? Yes. One too rarely sees students from the university writing programs and English classes attend and participate in the smaller venue readings and open mics. And Seattle generally suffers from excessive political correctness, and this can lead to some prematurely dismissive attitudes towards anything perceived as culturally conservative (e.g., rhyme and meter). But… I’d rather emphasize the good. Our fine city boasts numerous excellent poets and performance venues, and I’m glad to be here, right in the thick of it.

EB: How does poetry change people? Or does it?

DH: “or the sun’s/ Faint friendliness on the wall some lonely/ Rain-ceased midsummer evening.” — Philip Larkin

“We slowed again,/ And as the tightened brakes took hold, there swelled/ A sense of falling, like an arrow-shower/ Sent out of sight, somewhere becoming rain.” — Philip Larkin

“In friendship false, implacable in hate;/ Resolv’d to ruin or to rule the State.” — John Dryden

“The grave’s a fine and private place,/ But none, I think, do there embrace.” — Andrew Marvell

“The ides of March are come.” “Ay, Caesar, but not gone.” — William Shakespeare

These and many other eloquent, thematically rich poetic offerings inspired me to study poetry, to stay up until 4 a.m. to refine a poem, to refresh my spirit in another’s talent to develop my own. Yes, poetry can change a person! It inspires, captivates, maddens, titillates, deepens, challenges, educates, enriches, emboldens, and refines. I cite some of my early favorite lines from the great tradition, but I read widely, and poets of both genders and from diverse international regions have changed my world view and improved my craft. And, of course, millions of people can attest to poetry’s power! Their choice of favorite poets and lines would undoubtedly differ from mine, but we share the common experience of being moved by words: indeed, the right words in the right order in the right rhythm. And sometimes you never forget ’em.

EB: What advice have you got for poets?

DH: I’m guessing you would prefer I practice the concision I so eagerly preach. I will try, then, to restrain my pedagogic tendencies. There is too much to say, but… here are a dozen suggestions:

1) Read widely in diverse traditions.

2) Don’t stray too far from sincerity, but don’t preach.

3) Poetry is the intersection of language and music. Consider, then, the relationship between rhythm and resonance.

4) Master punctuation, so if you break a rule you understand why and can do so to intelligent effect. Do not dismiss knowledge of punctuation, grammar, and syntax as pedantry.

5) Distinguish urbanity from snobbery and earthiness from crudity.

6) Write many dramatic monologues–or “persona poems,” if you prefer that term. Cultivate empathy; enrich your voice.

7) Refine your skill to render a scene through imagery–precisely phrased physical imagery that evokes a scene. An old-fashioned skill and none the worse for it.

8) Browse through a dictionary for at least fifteen minutes weekly. And study the etymologies of words… Soak in their poetry.

9) Try hard to avoid blaming others for your not being internationally famous by the time you are twenty-five. Organize readings, volunteer at book fairs, host open mics, and post links to others’ websites on your own. Link with kindred spirits, and make your own fate! Blame is toxic. It’s not always wrong to blame, but it poisons the soul and work of many a poet. Try hard not to go there, although I understand you might have good reason to be angry with the literati. But… try to stay positive.

10) Try to get your work published by focusing on journals other than The New Yorker, Poetry, The Paris Review, and The Atlantic. Look for editors and journals that share your perspectives and publish at least one poem per hundred submitted. Fame will come eventually if you are talented and persistent. Build up your confidence and literary resume with real publications and performances, not fantasies of prestige readings before thousands. Focus on the gritty, unglamorous details of real career-building, if you are indeed ambitious.

11) Memorize at least six of your favorite poems of fourteen or fewer lines.

12) Distinguish absolutism from principle, skepticism from nihilism, and enlightened self-interest from narcissism. And don’t forget to have fun!

EB: Do you have some favorite poets?

DH: Yes. Let me list some of them:

Philip Larkin

W. H. Auden

W. B. Yeats

Geoffrey Chaucer

William Shakespeare

Ben Jonson

Andrew Marvell

John Dryden

Matthew Prior

Alexander Pope

Jonathan Swift

Oliver Goldsmith

A. E. Stallings

Gail White

Alison Joseph

Marilyn Nelson

Belle Randall

Rafael Campo

David Mason

William Dunlop

Michael Spence

Tu Fu

Heinrich Heine

Homer

Martial

Ovid

Catullus

Richard Wakefield

and dozens and dozens more (Please forgive me, my friends, if any of you feel slighted by not mentioning you! I’m lucky to know so many fine poets, and I can list only so many here!)

EB: Where can readers get Rose Alley Press books?

DH: I’m working to make books available for sale directly through my website: www.rosealleypress.com. That’s not ready yet, so contact me directly via email: rosealleypress@juno.com. Also, the following Seattle-area bookstores should either stock requested Rose Alley Press titles or be able to order them: University Book Store, Open Books, Elliott Bay Book Company, BookTree Kirkland, or Edmonds Bookshop. Island Books and Queen Anne Avenue Books likely could also special order them, and I do fulfill orders from my wholesaler, Baker & Taylor. I’ll have a booth, too, at the Ashland Literary Arts Festival at Hannon Library on October 28th. Come by and introduce yourself. I’ll be reading my poetry at the festival, too, so I hope to see you there–and, yes, I’ll have Rose Alley Press books for sale at my table.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

DH: Thank you, Ed, for relating such a thoughtful, challenging set of questions. I hope my answers are of use to you.

Follow

Follow