Chin Music Press was founded by Bruce Rutledge and Yuko Enomoto in 2002. Their mission is create “literary objects” — books that are a pleasure to touch as well as read. NPR describes them as “a triumphant kick in the pants for anyone who doubts the future of paper-and-ink books.” In 2014, Chin Music opened a bookstore in the Pike’s Place Market. You can read what Publisher’s Weekly said here. Publisher Bruce Rutledge sat down online for an interview about Chin Music Press.

Ed Battistella: How did Chin Music get started? You’ve been around for quite some time.

Bruce Rutledge: My wife Yuko Enomoto and I formed the company in 2002 while working with designer Craig Mod, who was finishing up his undergraduate degree at the University of Pennsylvania. As soon as he graduated, we hired him and sent him to Japan (I still don’t know how we managed to get him a work visa, but we did). Yuko and I had just returned to the States after working as journalists in Tokyo during the 1990s, and we were eager to publish books about Japan. Back then, we even printed in Japan, so having a production person there made sense. Plus, Craig was inspired on a daily basis by what he saw, which helped make our books keepsakes.

Bruce Rutledge: My wife Yuko Enomoto and I formed the company in 2002 while working with designer Craig Mod, who was finishing up his undergraduate degree at the University of Pennsylvania. As soon as he graduated, we hired him and sent him to Japan (I still don’t know how we managed to get him a work visa, but we did). Yuko and I had just returned to the States after working as journalists in Tokyo during the 1990s, and we were eager to publish books about Japan. Back then, we even printed in Japan, so having a production person there made sense. Plus, Craig was inspired on a daily basis by what he saw, which helped make our books keepsakes.

EB: How did you choose the name Chin Music?

BR: I loved that phrase since growing up in Cleveland, Ohio, listening to Mudcat Grant announce Indians games. He’d use that phrase every time a pitcher would throw a high-and-tight one at the batter. Then I came across it in Mark Twain’s writing. In Roughing It, a rube corners the parson and asks him to “jerk a little chin music for us” because one of their buddies has died and they want to give him a proper send-off. I did a little research and was thrilled to find how many different meanings “chin music” has had during its lifetime. It’s a phrase that evolves and stays relevant from age to age. Today, rappers use the phrase as does Shawn Michaels of the WWE with his “sweet chin music” knockout kick. Who knows what’s next.

EB: Tell us a little about your background.

BR: I grew up in Cleveland, went to Kenyon College, where I developed a lifelong love of literature, and then went to Japan on a lark to teach English for a year, thinking I’d come back and get a job with a newspaper. This was the mid 1980s. My dream was to be a foreign correspondent. Well, one year in Japan led to 17. While in Japan, I was like a white-collar Louis L’amour, dabbling in all sorts of media jobs. I copyedited, was a stringer for wire services, even did some TV and radio work, and later did translation and interpreting work. While I loved that life, it was meant for a young person, and as I got older, I knew I wanted to work in longer forms. Setting up an independent press seemed like the next logical step.

EB: In 2014, you opened a bookstore in the Pike’s Place Market. What prompted you to do that?

BR: I had always wanted to combine the press with a store, but it never made economic sense until 2014. Our store is less a Chin Music Press store than it is a celebration of indie press in the Pacific Northwest. For me, it’s all about creating places online and in the physical world where people can gather and share ideas and stories. These spaces are so necessary.

BR: I had always wanted to combine the press with a store, but it never made economic sense until 2014. Our store is less a Chin Music Press store than it is a celebration of indie press in the Pacific Northwest. For me, it’s all about creating places online and in the physical world where people can gather and share ideas and stories. These spaces are so necessary.

I also noticed that many presses had the same idea around the same time as us. It’s interesting to see presses like Melville House, Milkweed, Two Dollar Radio and others branch out with these physical spaces. It’s a bit of a trend, and I think it’s because so much of our communal space has been gutted by gentrification and other forces.

EB: Chin Music Press publishes some beautiful books. What do you look for in a book and how do you work with authors to convert a book into a work of art?

BR: We are more open to books with visual components than most literary presses. But it is not something we look for or try to force into a narrative. We approach every book we publish organically. We discuss what is the best way to physically present the story. And usually, we come up with something unique and lasting. I think it boils down to taking the time to consider each title and not relying on a cookie-cutter approach.

Over the years, we’ve tended to attract authors who are looking for their book to be beautifully rendered. Authors who have published with large houses come to us because they want one objet in their oeuvre. We’ve gained a reputation for being able to do that.

EB: What do you look for in an author?

BR: Patience and an understanding that what we are attempting to do is very, very hard and often doesn’t make money. Also, a willingness to hustle. The author becomes part of our family for at least a year or so and sometimes for a lifetime. They need to work as hard as we do at getting their book in front of people.

EB: Let me ask about independent publishing more generally–what you call the publishing ecosystem. What’s the role of independent publishers like Chin Music in American book culture?

BR: We’re the risk takers. For example, our first two books were hardbacks without jackets in 2005. In 2010, The Guardian wrote about this “new fashion for going without wrappers.” Well, between 2005 and 2010, indie presses created that trend. We took the risk. That happens over and over. Without indie presses, the literary landscape would be arid.

EB: You have been publishing for awhile. What have you learned since beginning your press?

BR: I’ve learned to be a fluid thinker. Some of our best successes have come when we have broken from our original game plan. We did several books about New Orleans after Katrina that sold very well. That wasn’t in the game plan. We’ve also done design and editorial work for hire to stabilize our bottom line. I wasn’t expecting that to be a revenue source. You have to think and act like an entrepreneur but with no end game where a venture capitalist funds you. It’s eternal hardscrabble.

EB: What advice have you got for potential authors?

BR: Research the press you are pitching to. Show a willingness to help with sales and marketing. Show an understanding of the industry, or if you don’t have that, at least show empathy for what we do. Understand that going with an indie press to publish your book is in no way like going with a big NY firm. The economics are completely different as is the culture.

EB: Are there some forthcoming books you can highlight for us?

EB: Are there some forthcoming books you can highlight for us?

BR: We’re about to publish Timber Curtain, a collection of poetry about Richard Hugo and the Richard Hugo House, by Frances McCue. It is so timely and eloquent. It is coming out in tandem with a documentary about the Richard Hugo House called Where the House Was. Well, actually, the book will come out first, and I imagine the documentary will be ready early next year. Frances experiments with erasures, and that posed an interesting design challenge for us. I think our designer, Dan Shafer, handled it with aplomb. Timber Curtain will be out in late September.

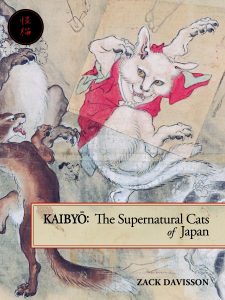

Soon after that, on Nov. 1, we’ll be doing our first co-publishing project with Mercuria Press of Portland. Mercuria Press is run by Carla Girard, who is the designer behind some of our most beautiful books. We’ll be co-publishing a series of books that explore aspects of Japan, and the first one is Kaibyo: The Supernatural Cats of Japan. It’s filled with woodblock prints depicting these supernatural cats and writing by Zack Davisson that helps us understand Japan’s relationship with cats. It’s a gorgeous book that will attract both Japanophiles and cat lovers. For Japanophiles who also love cats, it may simply be too much!

Soon after that, on Nov. 1, we’ll be doing our first co-publishing project with Mercuria Press of Portland. Mercuria Press is run by Carla Girard, who is the designer behind some of our most beautiful books. We’ll be co-publishing a series of books that explore aspects of Japan, and the first one is Kaibyo: The Supernatural Cats of Japan. It’s filled with woodblock prints depicting these supernatural cats and writing by Zack Davisson that helps us understand Japan’s relationship with cats. It’s a gorgeous book that will attract both Japanophiles and cat lovers. For Japanophiles who also love cats, it may simply be too much!

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

BR: Thanks for doing what you do, Ed.

Follow

Follow