Peter R. Field was a story analyst for Miramax Films and New Line Cinema in New York, and is currently an MFA candidate in Dramatic Writing from Spalding University in Louisville, Kentucky. He was Student Assistant Editor on The Louisville Review and served on the Willamette Writers Board of Directors for four years. He is the founding editor of The Timberline Review.

Peter R. Field was a story analyst for Miramax Films and New Line Cinema in New York, and is currently an MFA candidate in Dramatic Writing from Spalding University in Louisville, Kentucky. He was Student Assistant Editor on The Louisville Review and served on the Willamette Writers Board of Directors for four years. He is the founding editor of The Timberline Review.

EB: Tell us a little about The Timberline Review.

PF: The Timberline Review started up at the end of 2014 with a first issue publication date of August 2015, what we thought might be the only issue. The idea was to give Willamette Writers members a gift in celebration of the organization’s 50th anniversary. Once we realized the original concept would be much stronger by including submissions from all over the world, we expanded the guidelines. Thanks to the internet, and a modest online presence, the whole notion of the timberline seemed to spread enthusiastically. Issue #4 is now available!

Before you ask, let me explain a little about the timberline. Pam Wells, my founding co-editor, and I were brainstorming names and kept returning to what seemed to us to be powerful physical images of the Pacific Northwest. Rocks. Water. Trees. So much great writing includes that tangible, visceral connection to place. I thought of the timberline, that ecological edge on the mountain where the trees just stop growing. The Timberline Literary Review sounded like a good name. Pam instantly took to it, but she dropped the Literary.

I should also mention that, after the first issue, we made the decision to pay the writers! Yes, we pay our contributors a modest one-time use fee of $25. Incredible as it may sound, this in itself sets The Timberline Review apart from hundreds of journals that pay nothing. Let me also mention that the journal is funded by Willamette Writers (an Oregon non-profit in support of writers everywhere), and staffed entirely by volunteers.

EB: What sorts of writing are you interested in receiving?

PF: First and foremost, we’re not looking for writing, per se, about trees, despite what our name suggests. The Timberline Review publishes new works of short fiction, creative nonfiction, poetry, and essays, from emerging writers and well-established writers, and everywhere in between. We’ve taken pieces from retired doctors, social workers, lawyers, several of whom have seen their work in print for the first time in The Timberline Review. We’ve received some great writing from playwrights, writing in fiction for the first time, and from writers exploring hybrid narrative forms. The mission statement says we seek strong, brave writing that speaks to the times we live in. I know that may sound abstract, but I want to emphasize a sense of urgency, and dialogue, in the literary culture between writers and readers. This goes to the heart of everything, really, the importance of art, and artists, and keeping the conversation going. You might say The Timberline Review enables a little part of that conversation.

EB: How did you and editor Pam Wells get involved with this venture?

PF: Way back in 2014, I was on the Willamette Writers board of directors, and during one board meeting we were engaged in a free-floating discussion about the 50th anniversary coming up (in 2015). Pam happened to be at that meeting, and when I suggested doing a literary journal, she responded enthusiastically. There was a lot of back and forth, hammering out details regarding design, printing, submissions, staffing. We talked to freelance writer and editor Eric Witchey. We talked to Karen Mann, Managing Editor of The Louisville Review. We sought advice from Portland writer Brian Doyle, also the editor of Portland Magazine. Brian gave us lists of other publications and resources he thought we could take inspiration from. And he gave us a powerful essay for our first issue, “The Manner of his Murder,” which received a special mention in the 2017 Pushcart Anthology.

Brian also wrote a foreword for that first issue, a distinctly Doylesque version of our mission statement, that starts with the declaration. “Well, you would have to be four kinds of silly to start a magazine these days. You would have to be some fascinating amalgam of brave and crazy.” It’s worth reading in its entirety, but this short excerpt captures the gist of what we’re about:

“…if we don’t catch and trade and foment and spark and share stories of substance and pop and verve and zest and pith and fury, we will be slathered by an endless insipid ocean of sales pitches and lies. And that would be a shame.” (used with permission of author)

EB: What’s featured in the current issue?

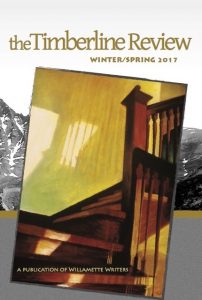

PF: Another feature of The Timberline Review is our use of cover art from local artists. Our first issue featured a gorgeous woodblock engraving by Kevin Clark, an artist in Roseburg. Issue #2 had a cover from an I-phone photograph of Haystack Rock, by Corvallis photographer Bill Laing. The third issue used a portrait by Portland artist Judy Biesanz, and the current issue, Winter/Spring 2017, features an image from another Portland visual artist, John Fisher, that strikes me as oddly fitting to our purpose. The title of the piece, “Ascension,” says it all.

PF: Another feature of The Timberline Review is our use of cover art from local artists. Our first issue featured a gorgeous woodblock engraving by Kevin Clark, an artist in Roseburg. Issue #2 had a cover from an I-phone photograph of Haystack Rock, by Corvallis photographer Bill Laing. The third issue used a portrait by Portland artist Judy Biesanz, and the current issue, Winter/Spring 2017, features an image from another Portland visual artist, John Fisher, that strikes me as oddly fitting to our purpose. The title of the piece, “Ascension,” says it all.

So what’s inside the cover? New poetry from several local poets, Kim Stafford, Brittney Corrigan, Devon Balwit, a lovely poem from Julie Price, a poet who lives in Illinois (and whose work was recognized in 2016 as the winner of The Rattle poetry prize). A terrific story from Jaime Balboa, a Los Angeles writer, inspired by a tragic news story, but told almost as a modern day fairy tale. That piece is called “Raziel’s Last Enchantment.” This is a story that must be told, but it’s not a light piece. Another piece that seems to take issue with the conventions of narrative form is Suzanne Cody’s “Island (I),” both inviting and startling.

Mike Francis, a writer from the Oregonian, gave us a first-person stream-of-consciousness account of his experience as an embedded journalist in Iraq. Natasha Tynes, from Rockville, Maryland, shares a fictional perspective of a would-be Jordanian emigrant in “Uniform.” Even though we don’t request specifically themed material, themes do seem to emerge that complement and counterpoint and more or less peacefully co-exist with each other. “Halab”, by Tala Abu Rahmeh, and Chris Ellery’s “Sparkler”, give us two distinct views of Aleppo.

EB: What’s been the most surprising thing about launching The Timberline Review?

PF: Maybe more of a discovery, than a surprise, but what I love about the journal is the eclectic nature of the whole process. It’s a process of assembling parts into a collage, in this case, literary works of different forms, with this amazing variety of voices and ideas. Sometimes the term aggregation is used to describe a collection like this, but I prefer to think of it as an assemblage, which hopefully stands on its own as a distinctive form.

It’s definitely been a surprise at how well the journal has been received, and how, as a new tangible artifact of contemporary culture, we’ve emerged from the “endless insipid ocean” to stake this claim on the literary landscape.

strong>EB: What other writing projects are you involved in besides The Timberline Review?

PF: I’m at the end of a low-residency MFA program, through Spalding University, in Louisville, Kentucky. I’ve written a screenplay that I’m shopping in Hollywood. And I’ve got a nonfiction book proposal I’m working on in the middle of the night. Pam has decided to move on from her role as editor. She’s deeply involved with the graduate program in book publishing at Portland State University.

Issue #5, the Summer/Fall 2017 issue, which is now open for submissions through April 30th, will go on with new editorial staff.

Stevan Allred, a Portland writer known for his book A Simplified Map of the Real World, published by Forest Avenue Press in 2013, joins us as fiction editor. C. Wade Bentley, a poet and teacher who lives in Salt Lake City, returns for his second stint as poetry editor.

I mentioned Brian Doyle’s role in the genesis of The Timberline Review, and we’ve also included him on our advisory board, along with Per Henningsgaard, director of the PSU Book Publishing program.

EB: How can readers get a copy of The Timberline Review?

PF: The Timberline Review is available through the website(timberlinereview.com), for single issue purchase, or by subscription. A number of local bookstores carry us — Powell’s, Annie Bloom’s, Broadway Books. The Southern Oregon Chapter of Willamette Writers usually has copies for sale at their meetings ). We get around to various events, Wordstock, Poets & Writers, AWP. We’re in a few local libraries in Portland and Corvallis. Bloomsbury Books might have a few copies on the shelf by the time you read this.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

PF: Ed, this has been a delight to talk with you about The Timberline Review, and I want to encourage every writer and reader out there to find a way to participate in our cultural discussion, a conversation that must never end.

Follow

Follow