Earlier this year, Literary Ashland interviewed Diane L. Goeres-Gardner. Her book

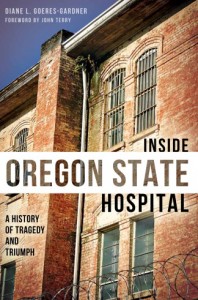

Inside Oregon State Hospital: A History of Tragedy and Triumph has recently been published by The History Press.

Diane Goeres-Gardner is a fifth-generation Oregonian, with roots in Tillamook County as early as 1852. She has a master’s degree from the University of Oregon where she studied with poet Ralph Salisbury. Her book Necktie Parties: A History of Legal Executions in Oregon, 1851-1905, was released by Caxton Press in 2005 and her Murder, Morality and Madness: Women Criminals in Early Oregon appeared in 2009, also by Caxton. Her book Images of America: Roseburg was published by Arcadia Press in 2010, part of its Images of America series, and for a history of the state hospital in images, see Goeres-Gardner’s Images of America: Oregon Asylum.

EB: How did you get interested in the Oregon State Hospital?

EB: How did you get interested in the Oregon State Hospital?

DG: While writing my second book, Murder, Morality and Madness: Women Criminals in Early Oregon I did some research into Oregon State Hospital (OSH) because before 1900 women prisoners were often sent to OSH in lieu of leaving them in isolation for so many years. The diagnosis female patients were assigned all seemed to revolve around the fact they were female, such as menopause, giving birth, and taking care of children, etc. I thought that was strange. My research also revealed that no one had ever written a history about the hospital. After that I was hooked.

EB: What was the research process like?

DG: The research was very sporadic and extremely difficult. The hospital itself had almost no archived information. Even the photos they had were mostly duplicates of photos held in other archives. I did find a file about the Calbreath family at the Oregon Historical Society, but they had almost nothing on the hospital either. That meant my main sources of information were the State Archives, the State Library, and the microfilm files at the University of Oregon, which stores copies of Oregon’s newspapers. When you look at the endnotes in the book, almost all are from those three sources.

EB: I want to ask about eugenics and sterilization. About 2,600 people were sterilized in Oregon between 1917 and 1983. Was Oregon typical in this? You mention some eugenics proponents like Bethenia Owens-Adair. What was her impact?

DG: Oregon’s enthusiastic adoption of Eugenics doctrine was not typical of other states. California sterilized over 20,000 victims and Oregon had the seventh highest number of victims (behind North Carolina, Virginia, Michigan, Georgia and Kansas). Many states didn’t sterilize anyone. Only Oregon targeted the gay community so harshly. Oregon’s use of sterilization was a “perfect storm” created by the kind of people elected to office during those years, a backlash against the gay community after a particularly well publicized expose in Portland, and the bias of the state’s institutional superintendents. Dr. Bethenia Owens-Adair was a persistent and influential proponent. She wrote the original bills Oregon’s legislatures finally approved. She just wouldn’t let it go. She was also well acquainted with the Applegate family and their mental illness problems. I believe that knowledge biased her toward the Eugenics philosophy.

EB: It was interesting that several members of the Applegate family were patients? How did so many Applegates end up in the asylum?

DG: I wanted the book to be more than just a collection of facts and figures. I wanted readers to feel the context of how patients experienced the hospital. To accomplish that, I needed to find patients in the hospital that I could research. The Applegate family was easy to research and had an extraordinary number of family members admitted to the asylum over a rather short period of time. I discovered and reported on eight members of the family committed to the hospital. There were actually two more that I didn’t mention in the book. Today we know that some kinds of mental illness do run through families. In the late 1800s people also knew from experience that some families had more incidents of mental illness than others. However they had extremely limited ways of dealing with it. Sending the patient to the Oregon State Asylum was just about their only option. There may have been other families with just as many patients in the hospital, however their names were less identifiable and harder to research.

EB: Funding seems to have always been an issue, as well as county-state disputes over funding. What did you conclude about the impact of funding on care.

DG: It is very costly to care for thousands, or even hundreds, of sick people who have no insurance and no way to pay for their care. Over the years funding issues have tormented not only the hospital, but all state institutions. Oregon is in a particularly vulnerable situation because the state’s only income is through property taxes and those have been capped. Also other states make the patient’s home county pay a portion of the expenses. Oregon doesn’t.

EB: You mention a celebrated 1914 dispute where a wife claimed that her husband was having her committed to gain control of her assets. Was this common?

DG: It may not have been common in Oregon, but it was always suspected. For many years Oregon laws protected women by prohibiting their husbands from divorcing them while they were in the hospital. The law made it very easy to have a person declared insane and a husband had greater power in front of a judge than a wife.

EB: The hospital changed its name from the Oregon Insane Asylum to the Oregon State Hospital? Did that reflect a change in its mission?

DG: Superintendent L. L. Rowland proposed changing the name as early as 1895 but it wasn’t acted upon until 1913 when a number of things changed. That year Oregon opened the Eastern Oregon State Hospital and the state discarded the old trustee system of supervision and changed to the Board of Control system. A new psychiatric and medical building was opened on campus in 1912 creating a more modern attitude toward mental illness. The mission was changed from warehousing people to trying to actively treat and cure mental illness. Certainly the term hospital had a more hopeful connotation than asylum.

EB: One long-time superintendent, Dean Brooks, allowed the film One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest to be filmed at the hospital, and even had a role in the film. Was the filming controversial?

DG: Dr. Brooks supported the project and wanted patients to be involved in all aspect of the movie’s filming. He believed it was beneficial for patients to be engaged in activities outside the hospital environment and that the movie would bring increased attention to the hospital’s needs. He did not think the movie attacked mental facilities as much as the authoritarian structure that so often surrounded them.

EB: I was fascinated by the various treatments: moral therapy, hydrotherapy, insulin and electroshock therapy, lobotomies. How did treatment evolve?

DG: OSH adopted various treatments as they developed across the United States. Treatments for mental illness went from basic incarceration to active remedies rather quickly. Soldiers returning from WWI and WWII with psychological problems created a need for better treatment modalities and OSH, like other hospitals, was eager to try them out. The need created the interest, and the interest created the cures.

EB: Funding, maintenance and staffing have always been issues, it seems. With the recent renovation, is the OSH turning a corner?

DG: Today the overcrowding is gone and instead of sharing a room with several other people, patients now live in private rooms. Their safety is no longer compromised by inadequate and outdated facilities. Staff can now focus on treating the patients instead of keeping buckets filling with rainwater from overflowing all over the floors. Superintendent Greg Roberts has reduced required staff overtime making the employees happier and healthier. All these improvements make it easier to focus on the important thing – helping patients get well and returning them to their communities.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

Follow

Follow