Here’s my third summer reading update featuring The Glass Rainbow, Girl Sleuth, The Gift of El Tio, and Winning at Aging.

The Glass Rainbow

I find myself tiring of some authors, but never James Lee Burke. The Glass Rainbow is 18th novel in the Dave Robicheaux series, about the morally complex deputy sheriff in fictional New Iberia, Louisiana. It shows the decaying feudal south at its most raw.

What keeps the Robicheaux series so interesting for me is Burke’s ability to show evil. He creates more villains in one book that other writers do in a career and part of the mystery is wondering whose evil will be banal and whose will be the most repugnant. In The Glass Rainbow, we get to choose from the drug dealer, the prison guard, the aging oligarch, the smarmy rich boy dating Robicheaux’s daughter, the corrupt alcoholic deputy, the ex-con celebrity writer, another mysterious ex-con, an ex-cop turned banker, and his cheating wife. That’s a lot of bad.

Burke’s writing is realistic and complex (no two-page chapters for him). Its realism generates both cynicism and optimism. Robicheaux and Purcel are stalwart— They act not just for the dead and defeated, but for those who have been fooled into not standing up for themselves. Rage and compassion drive them and the narrative forward. Robicheaux is better than most of us and Purcel a bit worse, but both are one injustice away from rage.

In his cheery fatalism, Purcel sees things for what they are. Robicheaux, the moralist and mystic has daytime visions and nightmares too. They never waver, never give in, and never hesitate, even when they should. But they think. They are the kind of experienced observers of people and motives that not only figure things out but figure out what they mean—Purcel reads Plutarch, for crying out loud—and Robicheaux quotes Orwell (explaining that “On the whole human beings want to be good, but not too good,and not all the time”).

The title, by the way, refers to a stained glass window that Timothy Abelard, the aging oligarch gaveto Layton Blanchet, an ex-cop who became rich for a time by exploiting poor folk. (His wife Carolyn, who is even worse describes him as someone who’d stealing a poor a widow’s last dime.). The light through the stained glass creates a rainbow of “awakened memories of goodness and childhood innocence, all of it to hide the ruination they had brought to the Caribbean-like fairyland they had inherited.” But it’s an illusion, showing how people like Blanchet deceive themselves and degrade themselves in the hopes of pleasing oligarchs, who just have contempt for them. Here is where the cynicism comes in to balance the quixotic optimism of Robicheaux and Purcel.

The Glass Rainbow is less plot driven than character-driven but as the evil unfolds the tension builds—first I’d read a chapter at a time, then fifty pages, then a hundred pages. Things don’t get tied up quite so neatly at the end— Robicheaux and Purcel are both shot in a gunfight and we are left wondering. But I’m counting on these two old warriors–the “Bobbsey Twins of Homicide” being back in a year or so.

Girl Sleuth

If I were to channel Nancy Drew, I would probably say that Melanie Rehak’s Girl Sleuth is swell. It’s more than swell though. It’s a sparkling history of the women who created Nancy Drew, the barriers they broke, their successes, fights, and tragedies, and the most of all the legacy they created. Rehak, a sleuth herself, finds clues in the correspondence between of women who negotiated Nancy over the years.

The story begins with Edward Stratemeyer, the New Jersey entrepreneur who developed the ghost-written series ideas with the Bobbsey Twins, Tom Swift, the Hardy Boys and later, Nancy Drew (who but for a good editor at Grosset & Dunlap might have been called Stella Strong). Stratemeyer had hired a young Iowa journalist to ghostwrite the books from his outlines and he edited and polished the result. When Stratemeyer died in 1930, barely a week after the first Nancy Drew was published, Tom, Frank, Joe, Bert, Nan, Flossie, Freddie, and the newly launched Nancy were nearly orphaned.

It was the height of the Great Depression (hmm—is height right should it be “the depths of the Great Depression”? Anyway, everyone was broke) and no one wanted to buy the Stratemeyer Syndicate.

Enter daughters Harriet Stratemeyer Adams and Edna Stratemeyer, who took over the business. Harriet was the driving force of the Syndicate and Edna eventually became a mostly silent partner (but her sister’s eventually bane). The Iowa journalist Mildred Wirt, eventually relocated to Toledo for her husband’s job, wrote most of the first thirty Nancy Drews. Wirt, the first woman to get a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Iowa, was as prolific as they come (she would eventually write over a hundred books). Harriet Adams in turn guided the syndicate through the Depression, lowering the ghost writers’ fees from $125 to $85 (per book!), and into the postwar period as girls reading habits changed and Nancy followed suit. As her popularity grew, Nancy dragged the aging Harriet into the 1960s and beyond.

There’s even a climax that is more Perry Mason than Nancy Drew–a legal showdown between Mildred and her old publisher Grosset & Dunlap on the eve of Nancy’s 50th anniversary. Here Rehak cranks up the mystery—who will be recognized as the real Carolyn Keene? Is it Harriet, who wrote increasingly detailed outlines and often argued with Mildred Wirt over Nancy’s characterization (refined and demure or confidently adventurous)? Or is it Mildred, who wrote Nancy through the early 1950s before eventually leaving the syndicate?

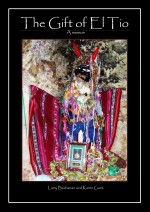

The Gift of El Tio

The Gift of El Tio is a book about change. What happens when silver is discovered and mined from a remote Quechua village in Bolivia. A village and a culture get relocated? Does that mean destruction or new opportunity? That was the question that exploration geologist Larry Buchanan and his wife, teacher Karen Gans, faced when Larry’s mining work took him to San Christobal, Bolivia. The couple viewed Larry’s project in different ways. Larry saw the mine as creating a new standard of living for poor villagers. Karen feared the destruction of their culture. The couple decided to live on site during the relocation of the village and document what happened.

The Gift of El Tio is a book about change. What happens when silver is discovered and mined from a remote Quechua village in Bolivia. A village and a culture get relocated? Does that mean destruction or new opportunity? That was the question that exploration geologist Larry Buchanan and his wife, teacher Karen Gans, faced when Larry’s mining work took him to San Christobal, Bolivia. The couple viewed Larry’s project in different ways. Larry saw the mine as creating a new standard of living for poor villagers. Karen feared the destruction of their culture. The couple decided to live on site during the relocation of the village and document what happened.

This splendid memoir tells that ten-year story. San Christobal was not the only thing to be changed, of course. Larry and Karen each became wiser as a result of their years in Bolivia. Together they traced and often influenced the preservation, development, and sustainability efforts that occurred. And they came to a new appreciation of cultural practices and beliefs they might earlier have dismissed as primitive and irrational.

The San Christobal silver deposit, by the way, was the largest ever discovered and Larry Buchanan received the 2006 Thayer Lindsley Award for the discovery—more or less the Nobel Prize of geology. In more ways than one, Larry shared the prize with El Tio, the god of the underground that the San Christobal villagers credited with the silver find.

What I especially liked about The Gift of El Tio was how the book took me, along with Larry and Karen, out of my comfort zone. I had never thought much about how the relocation and preservation efforts work, outside of the movies Avatar. So it was nice to see a real life example, with a different plot line but just as happy an ending.

Winning at Aging

John Kalb’s Winning at Aging is not your usual self-help book. There are the things you might expect from a book called Winning at Aging—advice on exercise, diet (low calories, low fat, no refined sugar, and so on) and supplements (C, D, Omega 3, and much more). And there are useful exercises for readers to do along the way—Lifesavers—and in the appendix–Lifeboats. The book’s real strength though is in its attitude. Kalb takes his readers seriously and doesn’t just provide platitudes and bromides. There is discussion of culture and history as well as summaries of and citations to medical and psychological research. And the book is enlivened with case studies, personal insights, and quotes from the likes Karl Jung, Victor Frankl, Joseph Campbell, E. B. White, and Marcel Proust (and Woody Allen too).

Kalb starts with the big paradox of aging. We all die, so how do you win a contest whose outcome is already known? His idea is to deal with the real symptoms of aging. Not just creaky joints, age spots, wrinkles, gray hair, and loss of hearing, but the emotional, social, and spiritual symptoms. Winning at aging means being as intentional about our emotional and mental selves as we are about our physical selves. And it means exploring the ways that we might sabotage ourselves in these efforts.

A large part of the book reports on Kalb’s research on happiness (yes, research not just musing), and that’s the real key to winning at aging. Being happy means pursuing social capital as well as financial and continuing to have goals–using your talents in the service of your authentic purpose. To do that we need to decide what gives us purpose, grace and worth as elders, and Kalb’s Lifesavers guide readers along that process.

It’s never too early start winning at aging, and I’m no longer willing to settle for a draw.

Winning at Aging brings me back to The Glass Rainbow. A recent Wall Street Journal article on “The (Really) Long Goodbye” pondered the fate of Robicheaux and others like J.P. Beaumont, Harry Bosch, and Matthew Scudder who are all aging in their long-running series (female characters seem to age more slowly for some reason). They’ve got grandkids, 401k plans, bad knees, and plenty of enemies, but they seem to get the job done. Fictional characters are pretty good at winning at aging.

Follow

Follow