Jan Wright is the founder and director of Wright Research and Archives, the archivist for Harry and David in Medford, Oregon, and the former Director of the Talent Historical Society. She is the author of Images of America: Talent (Arcadia, 2009). She is working on a book project to be titled Imperfect Apostle John Beeson, Advocate for Native Americans.

Jan Wright is the founder and director of Wright Research and Archives, the archivist for Harry and David in Medford, Oregon, and the former Director of the Talent Historical Society. She is the author of Images of America: Talent (Arcadia, 2009). She is working on a book project to be titled Imperfect Apostle John Beeson, Advocate for Native Americans.

EB: Can you tell our readers a little bit about John Beeson?

JW: Injustice made John Beeson squirm. When he saw something that inflicted pain or wrong on any group of people, particularly the American Indians, he took action. Regardless of the personal consequences to himself or his family, he went straight to the source of the problem and confronted politicians, Indian agents, volunteer Indian fighters, newspaper editors and unfeeling ministers. His fire kept a smoldering camp of Beeson haters who belittled him and his mission whenever they could. Somewhat of a mystic, he fell into Spiritualism and was visited by ghostly messengers who guided him from beyond the grave.

EB: How did you get interested in his story?

JW: I resisted John Beeson for years. I was more attracted to telling the locally significant story of his son, Welborn Beeson, as it unfolded from his amazing diaries. Of course, Welborn wrote about his father’s whereabouts in the east and what he said about the father son relationship fascinated me. My research trips to New York, Illinois and DC turned up so much information about John Beeson that I gave way to the story that had a more national appeal and was so intertwined with the fate of Native Americans.

EB: Beeson wrote the Plea for the Indians in 1857. How was that received?

JW: Written after he was forced to leave Oregon, a Plea for the Indians launched his long career as an advocate for the Indians. He used the book effectively as an introduction to the the East Coast lecture circle. To the city dwellers, he was considered a credible witness of the far west experience but generally the people of the West, derided and condemned him as too soft on “savages.” He eventually became a reliable speaker at suffrage gatherings, abolitionist meetings, churches, government councils and as a form of entertainment with a troupe of Indian singers. One of his speeches in Buffalo, NY was attended by President-Elect, Abraham Lincoln, on his way to his own inauguration. After Lincoln moved to the White House, John Beeson, was invited as a guest to deliver his Indian message along with his favored Indian songstress, Larooqua.

EB: He returned to Oregon later. How was he received by his family and the community?

JW: After being gone for 8 years 8 months and 1 day, John returned (in 1865) to his family on Wagner Creek near present day Talent, Oregon. It was not an easy adjustment to be once again in a rural setting with farm work to do. He was used to crowds of people paying to get in to see him, to making appeals before Congress, to organizing peace groups at the Cooper Union in New York, but on Wagner Creek he was a farmer behind the plow like the rest of his neighbors. His attempts to give lectures in Jacksonville and Ashland were not well attended and though people tolerated his presence, he was out of his element and not generally respected.

His wife, Ann, died while he was home but she only wanted her son, Welborn, to be at her side. John was in the field plowing corn and was unaware of her death until he saw the neighbors gathering at their home to prepare her body for burial.

In the fall of 1867 John left for the East Coast again, hoping he could still be of use to the Indians on a national level. He was 77 years old and nearly deaf on his final return to Oregon in 1880.

EB: His life—and his story–seem to be very relevant today, I think. What connections do you see to current affairs?

EB: His life—and his story–seem to be very relevant today, I think. What connections do you see to current affairs?

JW: He told the truth as he saw it, blew the whistle when he had to, and was willing to stand alone to face his enemies. He envisioned an America that stuck to its stated values and principles and engaged in a non-stop quest for justice as a full-time occupation. He lived on the stranger’s dime, traveled in stage coaches, trains and on foot to school houses, churches, state houses, mansions and cabins to organize a national movement to seek a better outcome for the Indians. His story was a microcosm of what was going on all over America. He walked up the steps of each state capitol, each neighborhood, and visited each congregation with the news of the day and with the same old story. He wore the mantle of leadership without seeking exorbitant compensation. That kind of leadership is manifest in today’s organizations (such as Indivisible) that keep the pressure on local representatives to mind the will of the people. Beeson’s struggles show us that each generation adds a personal narrative and a new baseline from which to start but each has to vigilantly improve the workings of democracy and combat greed, corruption and racism.

EB: There must be some interesting local sources on Beeson in the Talent and Southern Oregon Historical Society archives. What sorts of material are you finding?

JW: The Welborn Beeson diaries are the single most outstanding source of information about the Beeson family and the historical, social and political events in Southern Oregon. They span the years 1851-1893 and began when the Beeson’s still lived in Illinois. The diary was tucked away at the University of Oregon Special Collections until 2006 when the Talent Historical Society had them microfilmed and repatriated to Talent.

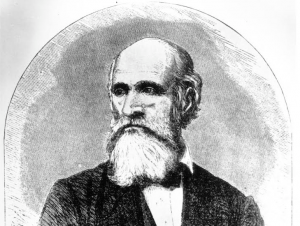

Southern Oregon Historical Society has a photo album which includes some photos of John Beeson and his family and copies of correspondence from friends and relatives. The living descendants of John and Ann Beeson are very much engaged with the progress of the book and have shared family photos and archived information.

EB: Are there important sources about Beeson elsewhere? I understand he lived in New York for a time.

JW: British born John and Ann Beeson arrived in New York in 1830 on the ship Samuel Robertson. John who had been trained as a confectioner in England, followed that occupation in Ithaca and Troy, NY until the family moved to Illinois. I have visited the New York state archives in Albany to do research on the Beeson family and have been in contact with the New York Public Library and the Cooper Union to obtain more information about John while he lived in that state.

I also visited the site of the farm in Illinois where Beesons lived for over 20 years and corresponded with the family who live on that property. My sister and I did extensive research at the courthouse in Ottawa, IL and elsewhere to document that portion of their lives. Newspapers from Maine to Rhode Island, from New York to Philadelphia, from Minnesota to Illinois and of course, Oregon all have multiple articles about John Beeson’s lectures and performances, his resolutions and petitions.

EB: You’ve launched a kickstarter campaign to support the research project. What was that experience like?

JW: The Kickstarter experience has changed the way I view the book. When the campaign ends on June 12th, I will know precisely who my audience is. I feel an overwhelming sense of gratitude and responsibility to make the book meet expectations and to follow the truth with accuracy and finesse. From the Mayor of Talent to a widow lady in Ashland, from my former boss, to my own children, people have come through for me and joined in the dream to resurrect John Beeson’s voice. I acknowledge that my journey has been a bit backwards, that the cart is before the horse when I talk about a book that does not yet exist.

In a sense, I am taking up my mission in much the same way as John Beeson did by asking for financial help to relieve me of the worry of earning my daily bread with a 9-5 job while I write the book.

Community support has made me a bit nicer and more disciplined and made me more likely to support others in their dreams as well.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

JW: It’s been a pleasure. Thank you.

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/235507129/imperfect-apostle-john-beeson-advocate-for-native

Follow

Follow