Abbigail N. Rosewood was born in Vietnam, where she lived until the age of twelve. In 2012, she was the recipient of the Michael Baughman Fiction Award and the Outstanding Graduating Student in Creative Writing Award from Southern Oregon University. Her works have published in such literary journals as The Adirondack Review, Columbia Journal, Green Hills Literary Lantern, and The Missing Slate.

Abbigail N. Rosewood was born in Vietnam, where she lived until the age of twelve. In 2012, she was the recipient of the Michael Baughman Fiction Award and the Outstanding Graduating Student in Creative Writing Award from Southern Oregon University. Her works have published in such literary journals as The Adirondack Review, Columbia Journal, Green Hills Literary Lantern, and The Missing Slate.

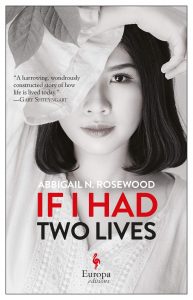

Abbigail Rosewood has a Master of Fine Arts in Fiction from Columbia University and an excerpt from her first novel, If I Had Two Lives, was awarded First Place in the Writers’ Workshop of Asheville Literary Fiction contest. If I Had Two Lives was released by Europa Editions this April.

James Cañón, author of Tales from the Town of Widows, calls If I Had Two Lives “the perfect novel of dislocation.” Gary Shteyngart, author of Super Sad True Love Story and Little Failure says it is “A harrowing, wondrously constructed story of childhood and a brilliant meditation on how life is lived today.”

Abbigail Rosewood currently lives and writes in New York. You can follow her at abbigailrosewood.com

Ed Battistella: Congratulations on the publication of If I Had Two Lives, which I really enjoyed. It’s a great read and a great accomplishment.

Abbigail N. Rosewood: Thank you for reading! It has been a pleasant surprise to receive so much support from friends and strangers, but it means a lot coming from you who taught me at SOU. I don’t know what it feels like for you reading your student’s work, but for me it is absolutely thrilling to be read by my professor—the ultimate A plus.

EB: It felt to me to be a novel about longing and wanting people to be what we needed them to be. Is that part of the immigrant experience do you think?

AR: Loneliness is a universal human condition and for those who migrate, it is both the prerequisite and outcome. It is impossible to be ripped off from your roots and not feel intensely isolated. Within an isolation chamber, memories resound much louder and manifest themselves again and again as the immigrant attempts to digest the pain of being psychically fractured—being between cultures, languages, memories, and between truths as well.

Yet I don’t think this is unique to the immigrant experience. All the time people gravitate towards familiarity, echoes of their childhood. Familiarity becomes a guiding post on who to love, what to eat, and unfairly who to hate and fear as well. In my novel, the narrator’s longing is so profound that she superimposes her memories onto people that are perhaps not genuinely anything like those from her childhood. Parts of her evolution is coming to the realization that she has failed to really see the person she claims to love for who they are.

EB: Can you tell us about the title? There is a nice reveal at the end but all through the book I was playing with different understandings of that. I wondered if you were intentionally giving the readers different ways to see that in some of the pairings of the characters.

AR: I’m curious to hear what you make of the title! I do hope for readers to get a multilayered understanding of the title. When someone says, “If I had two lives, I would…,” it sounds like the beginning of a wish, yet juggling two lives is a reality for many people. It is a gift to be both and neither, but it comes at an enormous cost.

Looking back, it is hard to pin point my intentions, but when writing I’m always asking questions. Narrative gives me the opportunity to create situations that are nuanced, emotionally and morally ambiguous, which can be demanding of readers. Art doesn’t offer neat conclusions: it can move, irritate, and even anger. It is my hope that readers can juggle the questions and hold all these contradictions in mind.

EB: If I Had Two Lives is story-driven, but from time to time you allow the protagonist some room to philosophize and reflect. What’s the key to adding that sort of depth without taking away from the narrative. Were you conscious of the moments when you had the main character meditate on life or did those moments just happen? Was she taking over?

AR: There are many successful literary works I admire that is only telling or showing. I try to balance both. In If I Had Two Lives, the protagonist’s way of expressing her feelings is often understated, which is essential to her character. Subtlety doesn’t work for everyone—I encountered a good amount of resistance from editors when my agent was trying to sell the book. Still, it is my firm belief that nothing can ever be subtle enough. Occasionally, however, it is useful to be exact, to give readers emotional anchors or affirmations of what they already know.

AR: There are many successful literary works I admire that is only telling or showing. I try to balance both. In If I Had Two Lives, the protagonist’s way of expressing her feelings is often understated, which is essential to her character. Subtlety doesn’t work for everyone—I encountered a good amount of resistance from editors when my agent was trying to sell the book. Still, it is my firm belief that nothing can ever be subtle enough. Occasionally, however, it is useful to be exact, to give readers emotional anchors or affirmations of what they already know.

EB: I enjoyed the writing and pace, and these was one matter of craft I especially wanted to ask you about: in the first part of the book you make a point of not using names—there is “the little girl,” “my mother,” and “my soldier,” and even the protagonist is nameless throughout. Can you talk about the namelessness?

AR: As soon as something is named it loses ambiguity, which to me is a great loss. It feels honest that my central characters should not be easily pinned down or defined, especially the protagonist because she suffers profoundly from the psychic ruptures of being in-between. I myself have a complicated relationship with names. I would love to live namelessly or go by a name that is cleansed of all assumptions like iLP78&R, but it is simply impractical. I suppose this might be one difference between life and fiction, the novel can afford some impracticalities in service of a higher truth.

EB: Was one of the lives easier to tell than the other? I liked the way you brought the lives together at the end.

AR: Thank you. It is hard to give any life the intricacies that it deserves. In that sense I am aware that like most novels, this one too is a failure. I started writing it when I was twenty-five, finished it at twenty-six, and published it at twenty-nine. A month before publication, I had one last chance to edit minor details. Because it has been a few year since I read it, I had enough distance to see how flawed it was, how full of naiveties. At some point, in order to publish, all writers have to contend with this reality—their ego—the arrogant idea that a work could be perfected. I think, art, if it were to really live, it must do so with errors, loose ends.

EB: What was the process of writing the novel like for you? Did much change from the earliest versions?

AR: It was the absolute best part of the whole thing. There is nothing more sublime than to surrender to the work to be congruent with aesthetic values, which I’m afraid to say, I put above all others. There are eight “drafts,” of the novel, although the original writing from the first draft has not changed, only shifted. Moments are expanded so that the work grows in volume. The novel happens to be my chosen medium so there are certain requirements to fulfill, one of which is length, but the emotional core can be expressed with a song, a brushstroke, a knife fight. I have great respect for poets for this reason, their ability to move worlds with a few syllables.

EB: Perhaps this is an unfair question but how much of the story is autobiographical? Or is the novel all fiction?

AR: A visual artist I know incorporates in her mixed-media paintings objects from her personal life like a piece of her son’s blanket from when he was a baby. My work is autobiographical in the sense that it is blanketed with emotional truths and emblemed with personal “objects”. My writing will always be honest in this way and autobiographical even if I were writing about dragons.

EB: What other current writing projects have you got happening?

AR: I have a second novel, which is still looking for a home.

EB: Thanks for talking with us. Good luck with If I Had Two Lives.

AR: Thank you so much, Ed, for the enlightening questions.

Follow

Follow