Ed Battistella: Congratulations on your book. Can you tell our readers a bit about it? What fascinates you about Yoeme Identity and the trope of the Yaqui warrior?

Ariel Zatarain Tumbaga: Thank you Ed. Yaqui Indigeneity: Epistemology, Diaspora, and the Construction of Yoeme Identity is a study of the representation of the Yoeme (or Yaqui) indigenous nation in Mexican and Chicana/o (Mexican American) literatures. In it, I study Native depictions with an emphasis on Yaqui history and culture. Until now, there has not been a book length study on this community’s representation in literature, despite their historical and political importance in Mexico, and their presence in the United States. Yaqui Indigeneity is also unique in that it looks to Yoeme history, cosmology, and traditional ceremonies (oral tradition known as etehoi and dance) as a basis for its literary analysis. Finally, it identifies a group of authors that I call Chicana/o-Yaqui writers, who are the sons and daughters of the Yoeme diaspora, often a direct result of Mexican Wars of Extermination perpetrated by federal and Sonoran state authorities. Yaqui Indigeneity works to retrieve an indigenous voice to nonindigenous portrayals of the Yoeme community.

What I found fascinating about the Yaqui warrior trope is the polysemy with which it has existed since the 1500s. Like other scholars, I was taken aback by the varying ways a Native nation’s assertion of its territorial tenure became, one the one hand, a subject of admiration by would-be conquerors, and on the other hand, justification for the dehumanization and violence colonial Spaniards, as well as 19th and 20th Mexican regimes, used in land grabbing efforts. Even today, Sonoran Mexicans will brag about the fierceness of their indigenous “ancestors,” while simultaneously considering it offensive to be called an indio. While the Yoeme people have a war history, that history is seldom told by them or from their perspectives.

EB: How did you first get interested in Yaqui culture?

AZT: This book has been a long time in the making, beginning with early childhood stories about invincible indigenous warriors and later with the Mexican and Chicana/o literatures I studied as a graduate student. My mother, a Mexican woman of Mayo descent, still tells popular and personal stories of Yaqui (Yoeme) and Mayo (Yoreme) history and people. She likes to remind people about the Mexican Revolution Era Mayo general Yocupicio who became governor of Sonora. As a child, she accompanied her Yoreme language-speaking grandmother in Mayo celebrations, like Santísima Trinidad in Júpare, San Juan in Navojoa, and Easter celebrations. She likes to tell us about the time when my tío Mario received a whipping from a sacred fariseo performer for disrespectfully mocking him during Holy Week. One of her favorite stories was about the defiant Yaqui warriors who drew a line on the ground to delineate their territory before impending Spanish invaders. The former story, based on the 1533 first Yaqui encounter with Spanish Conquistadors, is legendary and historical, but also serves as the beginning of the Yaqui warrior myth.

When I began studying Yoeme literary representations, I studied Yoeme culture out of necessity. In many instances, Yoeme defense of their territory is described as both political and religious. Therefore, I reasoned that studying their community’s presence in literature purely from a Western literary perspective would result in a superficial study of the Yaqui warrior myth.

EB: How has that construction of indigeneity evolved in literary works?

AZT: Indigeneity has had a long life in nonindigenous literature. Colonial literatures in Latin America were highly ethnographic, as if the power to rename indigenous people gave conquerors and colonial authorities a sense of power over them. For example, though they referred to themselves as Yoemem, they were nonetheless called Yaquis by Spanish priests and soldiers; the latter has persisted in public discourse. Literary and academic indigeneity has since been largely an exercise in denying Native people participation in their own representation. Nineteenth century representations were Romanticist depictions in which Native contemporaries represented peculiar national pasts differentiating Latin America from Europe and the United States. By the early twentieth century, literary depictions had become unapologetically anthropological works that, while well-meaning, often presented indigeneity as more Other than contemporary. Chicana/o literature had made progress in its representation of indigeneity, considering that Mexican Americans were racially and culturally part indigenous. At times, Chicana/o writers have focused heavily on pre-Columbian empires, which proposed Native American history and mythology to be as significant as Greco-Roman cultures. Though, a pre-Columbian focus has at times had the effect of obscuring the experiences of contemporary Native Peoples in Mexico and the United States. Indigeneity will keep changing in accordance with varying nonindigenous ideologies and political ebbs and flows, until we recognize and support self-identifying Native authors. Chapter five of Yaqui Indigeneity studies the question of Mexican American authors who are also of Native descent.

EB: You talk about the Yaqui as a transborder culture. Can you elaborate on that a bit?

AZT: The Yoeme people’s homeland is in southern Sonora, which is home to a coveted water source and fertile lands. This territory, and their much admired labor, made the Yoemem the targets of violent land grabbing efforts that resulted in waves of refugee migrations, as well as forced deportations, within Mexico, as well as into the United States. The result is the federally recognized Pascua Yaqui Tribe in Arizona. Arizona Yaquis participate in ceremonial traditions in the United States and across the border in Sonora. The diaspora resulting from the Wars of Extermination, of course, spread beyond Arizona, which forced many Yaquis to lose touch with their religion and culture, but not their history. In my final chapter, I offer my analysis of Chicana/o-Yaqui writers who use their writing as a form of cultural reclamation. These are writers of Yaqui descent who in some cases recovered some of their heritage through the process of researching their family histories. Seminal Chicano playwright Luis Valdez controversially represented the sacred deer dance in his play Mummified Deer as part of his artistic portrayal of Yaqui history and diaspora from Sonora, Mexico, into California. The late Yaqui-Chicano writer Miguel Méndez’s “Tata Casehua” reimagines heartbreaking instances of genocide against Yaqui resistance fighters and their families. Alma Luz Villanueva and Alfredo Véa Jr.’s works reveal creative adaptations of an impressive knowledge of Yoeme history and culture. And in the historical novel The City of Palaces premier noir novelist Michael Nava steps outside his genre to reimagine an award winning reinterpretation of the Mexican Revolution in part through Yaqui politics and religion. This body of work depicts individual and collective Native cultural-political experiences, and their historical significances, in Mexico and the U.S. So, the Yoeme people, culture, and the literature in which they appear are a transborder phenomenon.

EB: There was a lot of historical research involved in this book. Can you describe that process?

AZT: There are some studies on Yaqui history by authors like Evelyn Hu-Dehart and Edward H. Spicer, but not enough to satisfy a book length study like Yaqui Indigeneity. Luckily, the historical and geographical ubiquity of the Yoeme nation in Colonial, post-Independence, Revolution Era, and contemporary politics, has compelled historians to recognize them in their studies. Nonetheless, I relied on anthropological studies or anthropologically inspired biographies that informed my studies. For my chapter on the Mexican Revolution, Rosalio Moisés’s The Tall Candle: The Personal Chronicle of a Yaqui Indian, by archaeologists Jane Holden Curry and William Curry, provided me with real instances of Native survival, family disintegration, and diaspora into the United States. Jane Holden Kelley’s Yaqui Women: Contemporary Life Histories, which follows the lives of four Yaqui soldaderas, women who participated in the Revolution, was an invaluable source for its historical significance and its affirmation of Yaqui rituals during the Mexican Revolution. David Delgado Shorter’s We Will Dance Our Truth: Yaqui History in Yoeme Performances validated many of my conclusions regarding the importance of Yoeme religion, storytelling, and dance traditions. So, it was a real enlightening process of putting together relevant historical context from a multidisciplinary array of sources.

EB: What was the most surprising this you found in your research?

AZT: I was astonished not only by the Yoeme community’s hundreds of years of persistence, but also by their presence. As a collective, they staved off Spanish conquerors, thrived during colonial rule, rebelled after the War of Independence, fought in the Mexican Revolution, and recently publicly fought against the state appropriation of their water source. Individually, they participated in the California Gold Rush, served as military generals, were seminal Chicana/o activists, and, in the case of Alfredo Véa Jr. and Michael Nava, have been lawyers and award winning novelists. But I suspect that we might find it surprising partly because of how little people know about the Yoemem despite it all.

EB: Based on your research, how is your view of the Yaqui culture different from earlier work on the topic?

AZT: Well, Yaqui Indigeneity certainly follows in the footsteps of Spicer, HuDehart, and the work of Larry Evers and Yoeme scholar Felipe S. Molina. As I point out throughout my study, despite the complexity of many Mexican and Chicana/o works, their depictions of Yaqui culture has often been limited to a superficial understanding of deer dancers and warrior legends. Yoeme means “the people,” people who have been denied a public voice. And as such, their communities have given and sacrificed extraordinarily. I think that the more we learn about Native communities’ history and culture, the clearer their dehumanization, be it in the form of literature, regional legends and myths, military weaponry, or sports mascots.

EB: Thanks for talking with us.

AZT: On the contrary, it was my pleasure.

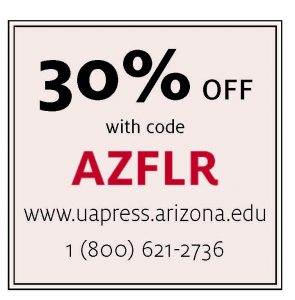

You can order YAQUI INDIGENEITY EPISTEMOLOGY, DIASPORA, AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF YOEME IDENTITY using the promotion code below.

Follow

Follow