Pulitzer Prize-winning writer George Dohrmann graduated from Notre Dame in 1995 with a B.A. in American Studies and later earned an MFA in creative writing from the University of San Francisco. He has worked at the Los Angeles Times, the St. Paul Pioneer Press in Minnesota, and Sports Illustrated, and he is currently a senior editor and writer for The Athletic. In addition, he has taught journalism at UC-Berkeley, Santa Clara University and Southern Oregon University. Dohrmann lives in Ashland.

Pulitzer Prize-winning writer George Dohrmann graduated from Notre Dame in 1995 with a B.A. in American Studies and later earned an MFA in creative writing from the University of San Francisco. He has worked at the Los Angeles Times, the St. Paul Pioneer Press in Minnesota, and Sports Illustrated, and he is currently a senior editor and writer for The Athletic. In addition, he has taught journalism at UC-Berkeley, Santa Clara University and Southern Oregon University. Dohrmann lives in Ashland.

He is the author of Play Their Hearts Out: A Coach, His Star Recruit, and the Youth Basketball Machine, , which won the PEN/ESPN Award for Literary Sports Writing, the Award for Excellence in Coverage of Youth Sports, and was Amazon’s pick as the best sports book of 2010.

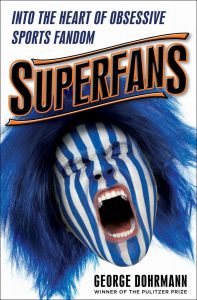

His latest book is Superfans: Into the Heart of Obsessive Sports Fandom, published in 2018 by Random House. Publishers Weekly says Superfans “gives soul to a much maligned and misunderstood aspect of sports.”

Ed Battistella: What prompted you to write Superfans?

George Dohrmann: I’ve been a sportswriter for more than 20 years and have had so many interactions with fans, good and bad. And in the last few years, with the explosion in popularity of social media, we see and hear from fans more and more. I felt like that while I was interacting with a lot of people who are diehard fans, I didn’t really understand why they were so devoted to their team, why they might do things that I would probably never do, even having been involved with sports in different ways most of my life. It really started with the simple idea that I should know more about the people who are consuming my work and out there in the world I cover.

EB: Would you consider yourself a superfan?

GD: When I was younger I was certainly a superfan of Notre Dame, where I went to school, but that has faded. Now, the only team I would say that about is the United State’s men’s national soccer team. That is the one team that I follow very closely and I will schedule my life around games.

EB: How do people become sports fans and then superfans?

GD: Most people become fans of a specific team because a parent or sibling is a fan of that team. It can happen other ways but that is the most common. Some people then make transition from casual fan to what I called superfans. In my book, the people profiled often ramped up their fandom at transition points in their lives, like when they got out of the military or got divorced or relocated to a new city for a job. That makes sense. People at a transition point are forming a new identity and they chose to dedicate some of who they are to being a fan of a specific team.

EB: What happens if you are a superfan and your team keeps losing?

GD: Well, studies show that very little happens. Researchers who study fans use a term, CORFing, which stands for Cutting Off Reflected Failure, to describe people who are tired of losing and so, to protect their self-esteem, they cut off some or all of their fandom. But that is not common. Most people will do things to protect their self-esteem from the blows of consistent losing, like lowering expectations for the team, but they won’t quit on their team entirely. It is too big a part of who they are to walk away, and even rooting for a loser can become, in a way, part of their identity and something they take pride in They can always say they are not a fair-weather fan.

EB: You talk about kids and fandom. Should parents involve young kids in fandom?

GD: Because of how big fandom is in some people’s lives, it would be very difficult for them to not show that side of themselves to their children, to hide this huge part of their identity. So, it is probably not a question of should people introduce kids into fandom but how they do it. Young kids want to see the world in black and white, so if you tell them: “Oregon is good and Oregon St is bad” or convey that in some other way they are going to embrace that almost too strongly. They might think of anyone who went to Oregon State as bad. They don’t understand nuance or have perspective at a young age. Also, sports fandom has a way of teaching kids to hate. Again, if you say you “hate” the Beavers, they will too. I think parents should minimize exposure to really passionate displays of fandom and also be careful with some of the words that are inherent in extreme fandom. When I am watching a game, my kids always ask: “Who are we rooting for?” Most of the time I tell them: “No one. We are just enjoying the game.” I want them to learn to watch because it can be pleasurable to see great athletes perform.

EB: You attended the Sports Psychology Forum to talk with academics researching fans. What was that experience like?

GD: It was a blast. It is so small-timey, and the handful of academics there know it and they sort of celebrate their irrelevance. We played mini-golf; we watched a lot of sports; we smelled Kentucky sweatshirts sprayed with deer urine (seriously). I learned a ton about how fans think because the researchers there are smart and passionate folks.

EB: What sports seems to have the most obsessive fans? And what sports have the least?

GD: I think college sports, especially football, have probably the most obsessive fans. That’s just an observation; there is no research showing that. College football fans (think Alabama fans or Ohio State or Georgia or Texas or a similar school) are indoctrinated at a very young age. Devotion to that school is something that runs in the family, and they are also often surrounded by others who are as devoted to that school. It leads to a strong connection.

EB: Can fandom go too far?

GD: Absolutely. Someone can become addicted. You’d look for any of the markers of addiction, like is their fandom negatively impacting their job or relationships or financial situation. There are clinical psychologists who treat fans for addiction. That said, most fans are doing fine and even the ones you might see on TV and think are crazy – many of whom I profile in the book – are normal people with very stable lives who are positive members of society.

EB: How have sports fans responded to the book?

GD: One of the more interesting reactions has been people complaining that I didn’t profile a fan or fan group related to their favorite team. I love that because it is the reaction of a superfan, someone for whom a team is such a huge part of their identity they can’t read a book about fans and not think: Why not my team? That is exactly the kind of behavior that made me want to write this book in the first place.

EB: Thanks for talking with us. I’m a fan of your book—in a good way.

GD: Thanks so much.

Visit George Dohrmann’s website http://georgedohrmann.com/ and follow him on Twitter at https://twitter.com/georgedohrmann.

Follow

Follow